‘Shojo Tsubaki’, A Freakshow

Underground manga artist Suehiro Maruo’s infamous masterpiece canonised a historical fascination towards the erotic-grotesque genre.

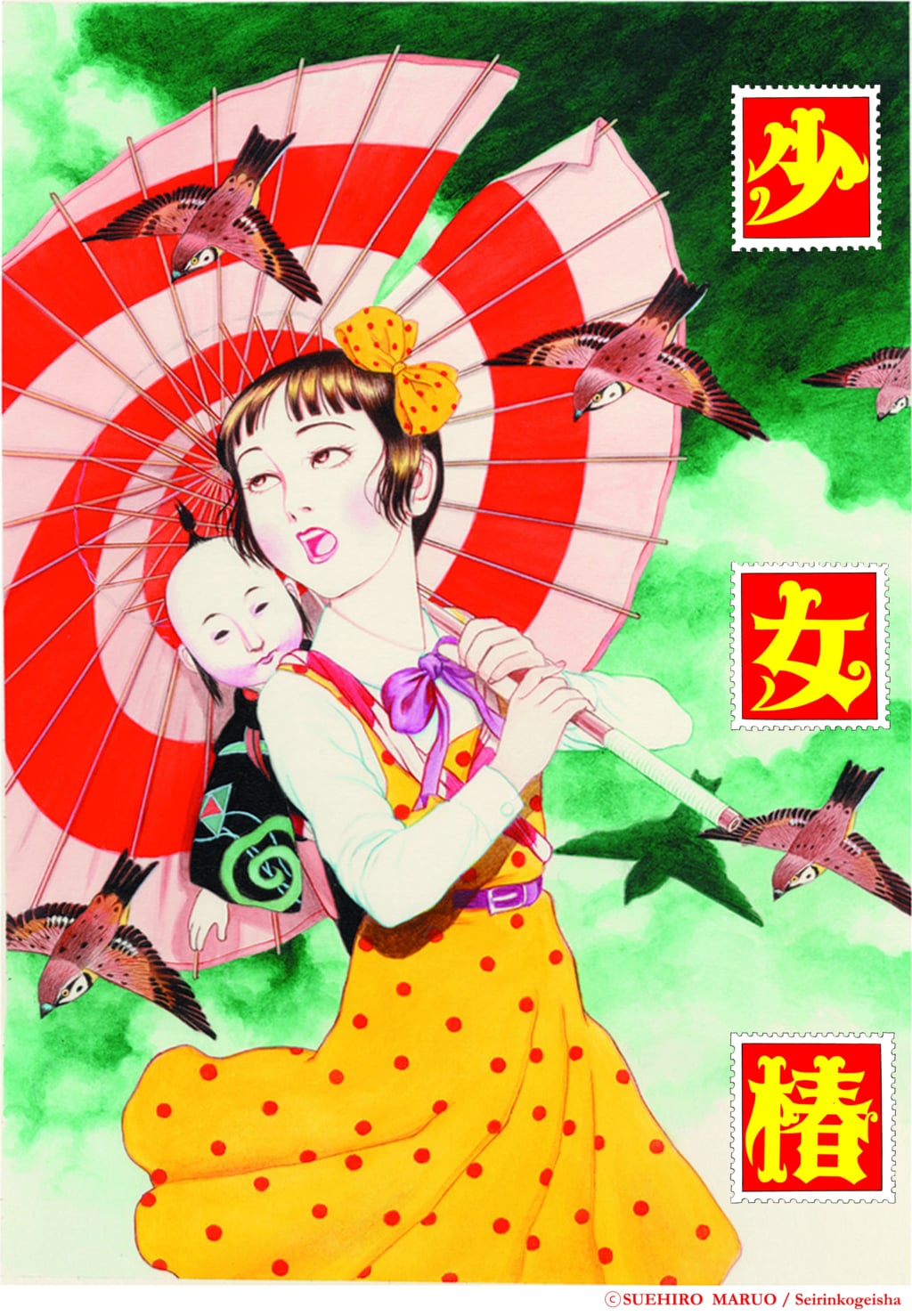

© Suehiro Maruo / Seirinkogeisha

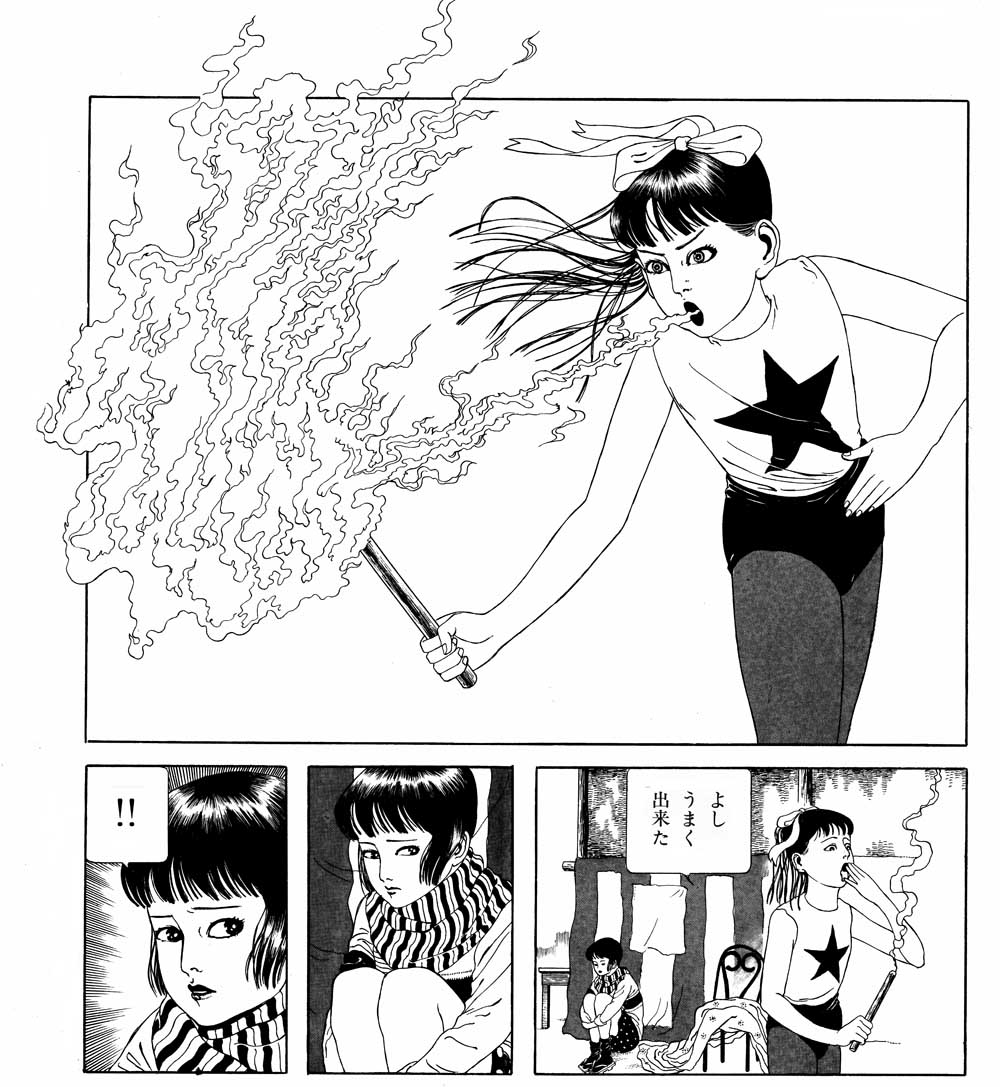

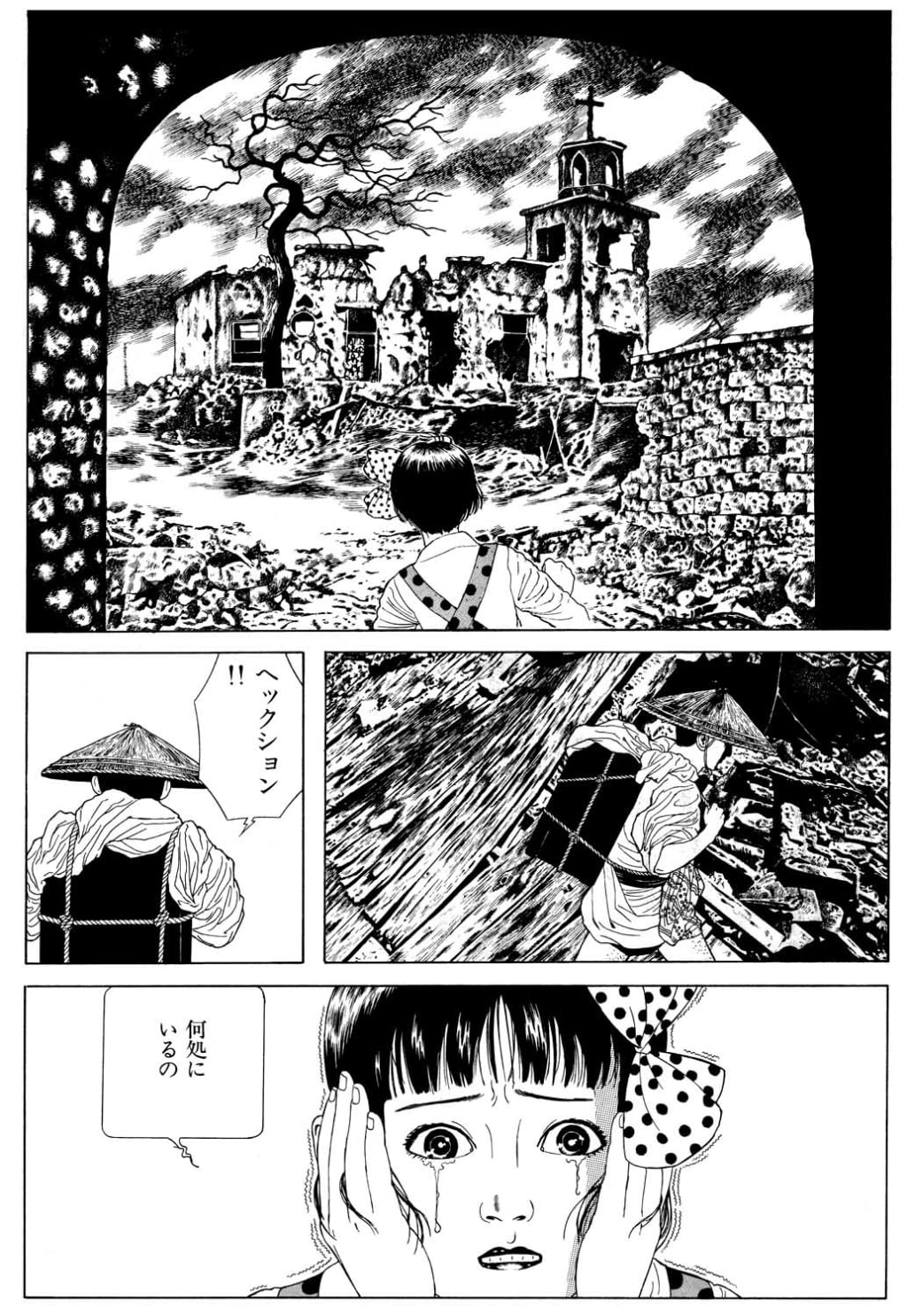

Unspeakable sexual violence in Suehiro Maruo’s Shojo Tsubaki (1984) leaves readers wondering whether the material in question should be banned literature. The misadventures of orphaned Midori, as she gets pulled from the streets into the abuses of a deranged circus troupe however, are illustrated with such haunting classical beauty that it is hard to turn away from them.

The 1984 graphic novel by underground manga’s legendary contributor takes a character from early Showa-era Kamishibai street theatre, injecting dark magic and nihilistic hedonism into her stories of hardship. Exceptional sequences—of desperate hallucinations, twisting body parts, and limbs crawling with bugs—recall the skittish atmosphere of Japan’s prewar decade. Today, the novel joins the most subversive trends of contemporary manga with even older traditions that have reconciled violence with a strange beauty.

Morbid Curiosity

Manga artist and painter Suehiro Maruo started his career at the age of 20 with Ribon no Kishi, a graphic horror whose title mimics a piece by his revered predecessor, Osamu Tezuka. Relentless in his visions, he came to be known as a key member of the avant-garde magazine Garo, and for adapting many horror stories of Edogawa Ranpo (a play on Edgar Allan Poe) in The Strange Tale of Panorama Island (2008) and The Caterpillar (2009).

Suehiro Maruo’s ornate style and bold subject matter invite comparisons to the last great masters of ukiyo-e, but his stories take place in 1920s Japan, when the clandestine ‘Ero Guro Nonsense’ literary phenomenon captured the public imagination with its erotic and grotesque takes on Japanese modernity. ‘Ero Guro’ was a bizarre bourgeois trend with a decadent twist, adopting the graphic violence of a certain ukiyo-e subset called Muzan-e to reflect on the delusional aspects of prewar Japan. In the work of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi in particular, obsessions with bondage, deformity, and decapitation came from the same traditional masters that stylistically informed Suehiro Maruo. But as a current artist synonymous with ‘Ero Guro’, the modern gore of works like Shojo Tsubaki evoke more recent moments when horror served as social commentary.

Forbidden Fantasies

The notorious case of Midori, Shojo Tsubaki‘s 1992 film adaptation, echoed the fate of ‘Ero-Guro’ texts forced to go underground. Though another cultural oddity, with a cinematography honouring the original Kamishibai and an eccentric soundtrack by J.A. Ceazer, its extreme content prompted an immediate universal ban. Fortunately, Suehiro Maruo’s undying reputation eventually allowed a DVD re-release outside of Japan, with occasional theatrical screenings retrieving it from oblivion. As the original novel, now out-of-print, has come to be zealously sought after, Shojo Tsubaki timelessly prevails as a dark classic of Japanese horror.

English versions of the manga Shojo Tsubaki—called Mr Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show—are distributed by Blast Books. The film, Midori, in French with English subtitles, was reissued in 2006 by Cine Malta and is available in DVD format.

© Suehiro Maruo / Seirinkogeisha

© Suehiro Maruo / Seirinkogeisha

© Suehiro Maruo / Seirinkogeisha

© Suehiro Maruo / Seirinkogeisha

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

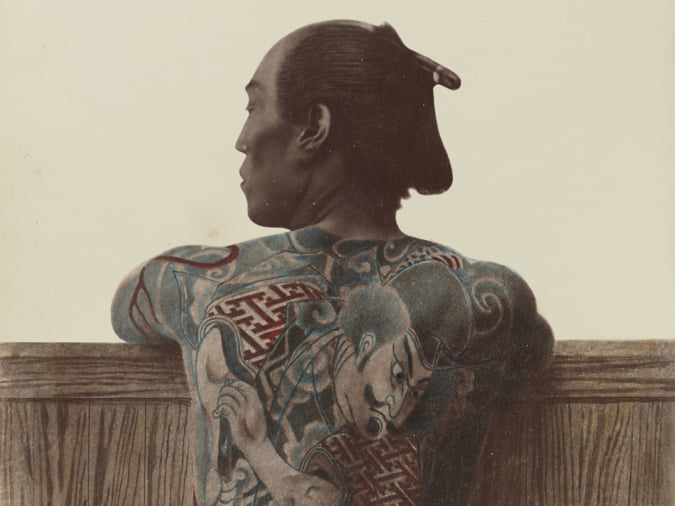

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

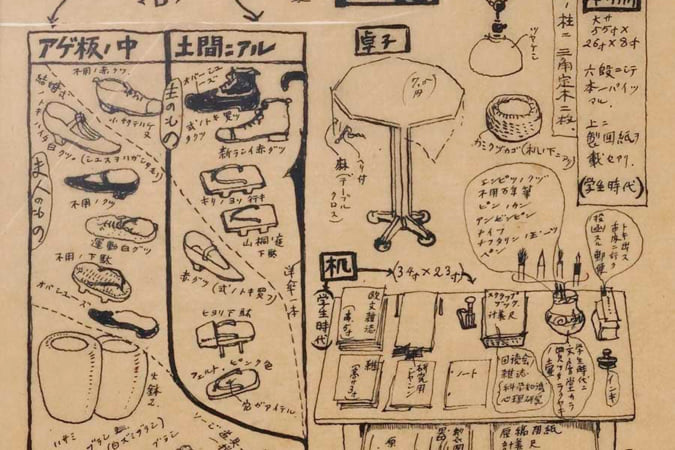

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.