Beautiful Africa

Navigated by photographer Nagi Yoshida

One day, Nagi Yoshida sat before her television mesmerised by what she saw. A show on the Maasai had captivated her—their noble gazes, their rich colours and art, as well as the scenery that sparked a lifetime passion and her journey into photography.

©Nagi Yoshida

Naked Bodies and Hearts

What prompted Yoshida’s obsession with African culture? How does she communicate with the locals? And, what does she strive to capture through her lens?

©Nagi Yoshida

Africa first attracted me when I saw the Maasai on television as a five-year-old. It was a little later when I learned that these were the Maasai. They wore blue clothing and necklaces, and they were so intriguing that I couldn’t take my eyes off them. This impression led me to become who I am now.

Until I was ten, the Maasai consumed my heart and mind. I honestly believed one day I would become Maasai. For some reason, I thought there was a button everyone had that, when pushed, would turn my skin dark. I shocked my parents one day when I asked when my skin would change colour. They responded, which was my first setback, explaining that no matter how hard I try Maasai are Africans and that I am not. I realised my skin colour would never change. I was distraught to the point of physically shaking.

Once I calmed down, I began to think: If I couldn’t become African, I at least want to meet them, which elicited icy responses from those around me. To my dismay, my preoccupation with Africa and Africans bothered many around me. I would say, ‘Africans are cool’, and people had a hard time with that, denying me my heroes. Those who knew little of these heroes were quick to disparage them. My frustration was mounting, and I was determined to do something about it. My proclamations continued, but it was more than ten years before I did anything about them. Then, at twenty-three, I visited Africa in 2009. I had been working as an illustrator for two years and had hit a slump. It was time to do something new, and Africa was calling. So, I went to a travel agency that specialised in African travel destinations. My first would be Ethiopia. In retrospect, I’m pleased this was the first place I visited.

I didn’t put too much thought into the trip because a local would be guiding me. I didn’t even speak English back then. About the only words I was able to render were, ‘How are you’? And, ‘I’m fine, thank you’. The guide seemed shocked when he discovered he’d have a client in tow who couldn’t communicate with him. However, he was a wonderful person, and he went to great lengths to communicate with gestures. Everyone I met treated me cordially, making the trip an even bigger event. These people whom I thought so much of took care of me. It felt a little like hanging out with Hollywood stars.

©Nagi Yoshida

In the two weeks I spent in Ethiopia, I visited five ethnic cultures, but they seemed businesslike—almost uninspiring. I took photos as they stood motionless. Then, they would leave. It was like that. More frustration mounted from my inability to tell them just how much I admired them and longed to meet them. From around 2011, I began organising my trips to Africa, which allowed me to visit more frequently and for longer periods of time. In 2012, I removed my clothing.

The hill-dwelling Koma people wear very little, covering their genitals with leaves while dancing to festive music. They allowed me to take photos. I remembered telling my interpreter two years before that I was going to remove my clothing, and he asked me if I was serious. However, I was embarrassed and only went halfway.

After I removed my clothing, the atmosphere transformed. The Koma became more earnest and told me through the interpreter that they had never met a foreigner like me. They knew that for people who normally cover their body removing clothing in public was difficult. They empathised with me. With every African ethnic culture, I have a similar response. However, by removing my clothing, I can enter their inner circle, and the sullen looks turn into smiles. In Namibia, I speak with actions rather than words and test to see how far I can run with it.

So far, I’ve visited seventeen of Africa’s fifty-four countries, and I keep passionately taking photographs—mostly because I feel I was denied my passion in my youth. I want people to look at my photos and see what I found in Africa and Africans. Too many people have an image of Africans as impoverished. A great Pulitzer Prize winning photo depicts a starving girl and a vulture. I want to counter these pictures and show people the richness I see in Africa as I stand with the ethnic nations.

Africa is home to many diverse groups and areas. I consider it my life’s work to interact with all of it.

Beautiful Bororo

Yoshida brought Bororo members to a location near Niamey, Niger’s capital city, to photograph against a backdrop of a lone railroad track in the desert.

The men of the Bororo compete for beauty titles at the Gerewol. The nomadic Bororo ethnic group live with their livestock as they travel from fresh pasture to fresh pasture. ©Nagi Yoshida

This was taken in the desert area twenty kilometres away from Niger’s capital, Niamey. The Bororo travelled nearly a thousand and a hundred kilometres for the photo-shoot with us, as they usually live in Northern Africa. ©Nagi Yoshida

The Bororo travel through areas where trains don’t pass, so Yoshida wanted to create a juxtaposition with the ethnic culture and a man-made object. ©Nagi Yoshida

To appeal more to women for Gerewol, each man takes as long as forty-five minutes to paint his face yellow. ©Nagi Yoshida

As a patriarchal society, the women of the Bororo come across as timid, yet their unique beauty stands out.

Straw hats, turbans, and headpieces with bags made from beads as they carry swords. ©Nagi Yoshida

Nagi Yoshida

A self-taught photographer who has made multiple visits to Africa since 2009, Yoshida focuses her lens on local ethnic cultures. She seeks out the beauty and ethnic interests in rare, back-country cultures to tell stories with her camera. Her accolades include Nikkei Business’ A Hundred People of the Next Generation in 2017 as well as The Cultural Prize from Kodansha Press the same year. Yoshida’s creations continue to delight and surprise the world.

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

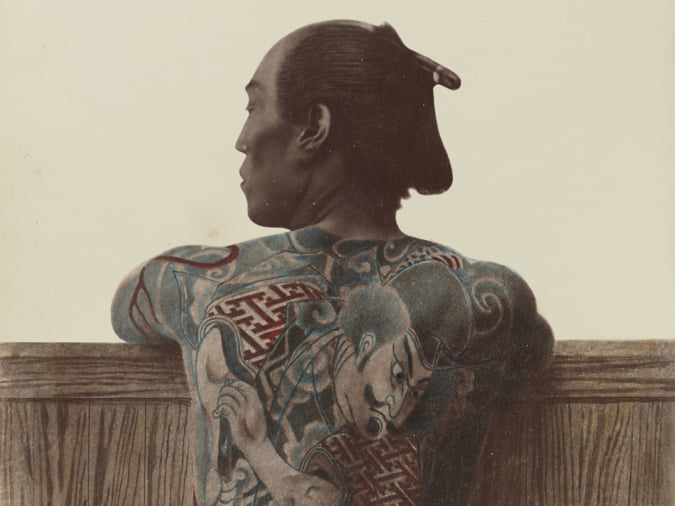

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

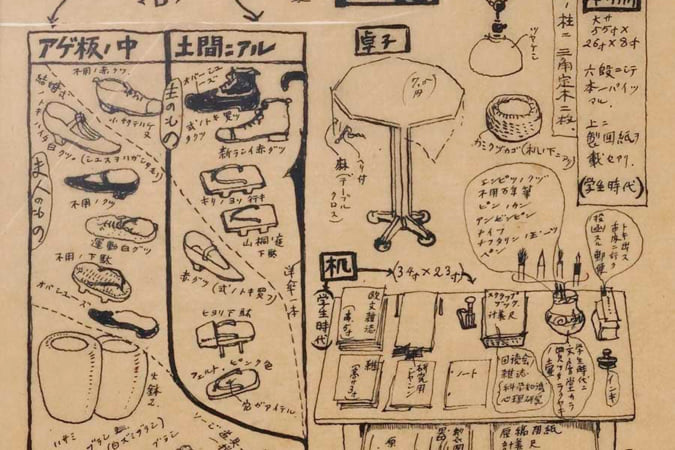

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.