Where Good Service is Given

Hotels with a Difference #01

Wherever you choose to stay in Japan, your hotel will always offer you a warm welcome. It’s nothing new, either…

The spa at Amanemu, fed by naturally warm water. Put on your swimwear and enjoy.

‘There are great many ryokan (Japanese guest houses), all very comfortable, that give travellers their first opportunity to experience the Japanese lifestyle. Although the comfort and service offered by Japanese ryokan are quite unlike anything with which foreigners are familiar, studying this new way of life will prove of great interest to tourists’. This is how the Japan Tourist Bureau, in the French-language Petit Guide du Japon that it published in 1936, sought to explain to future visitors the main difference between European-style hotels that ‘feature every modern comfort, good-quality food and attentive service’, and Japanese hospitality, in which hoteliers ‘are at pains to continually improve their ability to satisfy their guests’ desires’. The emphasis placed on service, succinctly summed up by the Japanese term omotenashi, is clearly apparent in the pocket guide, which at the time was designed to attract increasing numbers of tourists to the islands.

Good service remains a priority for those in the modern hotel trade, and is even a point that Japanese politicians have come to rely on. When they needed to convince the International Olympic Committee, meeting in Buenos Aires in September 2013, to let Tokyo host the 2020 Olympic Games, the Japanese representatives stressed, among other things, the idea of omotenashi, an approach that no other competing city could lay claim to. Their focus on this aspect of their bid paid off when the Olympics were awarded to Tokyo, while the expression became a familiar advertising slogan, both within Japan’s borders and beyond them. It’s a term that not only encompasses the kind of good service you’d experience in many hotels around the world, but also, and most importantly, it has a distinct local meaning that highlights a host’s ability to anticipate and meet guests’ needs and expectations. While you might have to request a particular service in some foreign hotels, the Japanese sense of hospitality is so highly developed that employees’ expert ability to cater to your desires in advance can sometimes take you aback.

In the 1920 edition of Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire, published in New York and long considered the definitive guidebook for anyone visiting Japan, T. PhilipTerry notes that: ‘The proprietors of these places […] usually give them their personal attention, and the limits to which they will go to make a foreign guest comfortable are oftentimes astonishing’.

The writer Lafcadio Hearn, best known for his book Kwaidan, gave an account of his experience at a guest house, which saw the owner make him a hot bath before insisting on washing Hearn by hand himself, while his wife made Hearn a delicious meal; the owner continually apologised that he was unable to do more. These days you can’t expect to be bathed by the owner of the ryokan you’re staying in, but the welcome that you receive will be similarly warm, indicative of your hosts’ efforts to ensure that you’re as comfortable as possible. In 1929, the Japan Hotel Association printed a brochure that bore the subtitle ‘At Your Service’. This key philosophy remains the mantra of the vast majority of hotels in Japan. From simple business hotels, designed for employees working away from home, to the bed-and-breakfast-style minshuku accommodation that’s especially common in regions where the hotel industry is still in its infancy. Whereas France and its ranking system sees the number of stars that a hotel is awarded supposedly reflects the quality of the service that it offers, Japan has no need for distinctions of this kind, as it is taken as a given that it offers its temporary guests the highest standards of comfort. Whether you’re staying in a chained-brand hotel of the type that are often found near stations or a more sophisticated ryokan, your bedding and the cleanliness of each room will give you little cause for complaint. What determines the difference in price between one hotel and another, meanwhile – a difference that can be quite striking – are its surroundings and the lengths to which the owner will go to ensure that guests are made to feel at home. It’s an approach that’s closely linked to the history of the many hotels and guest houses that have appeared since the Japanese began travelling around their country. Until the expansion of the railways in the late nineteenth century, journeys were limited as a result of Japan’s mountainous terrain, which made travel difficult. There were only five main routes, the most famous of which, the Tokaido, linked Edo, latter-day Tokyo, the political centre of the country, and Kyoto, the imperial capital. Travellers along the route would stop along the fifty-three stations, immortalised in prints by the masterful Hiroshige, where they were put up in yadoya, hatagoya or ryokan, to use the old Japanese terms for establishments that offered lodgings and food. Over 400 years later, these welcoming guest houses continue to offer visitors a warm reception, while retaining the pace of life of that bygone age. The most interesting approach, however, is to stay in a range of Japanese hotels, the renowned capsule hotels included, making sure that they each differ in style; you’ll realise that nothing else in the world compares with the sense of omotenashi that extends across the country.

Hotels with a Difference —

#01: Where Good Service is Given

#02: The Ryokan: Reworked and refined >

#03: Luxury Fit for a King >

#04: Panoramic Sea Views >

#05: Exteriors by Mother Nature Furnishings by Mount Fuji >

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

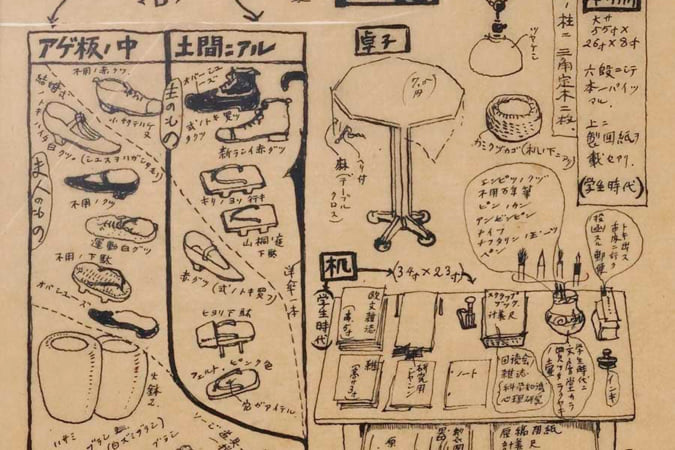

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

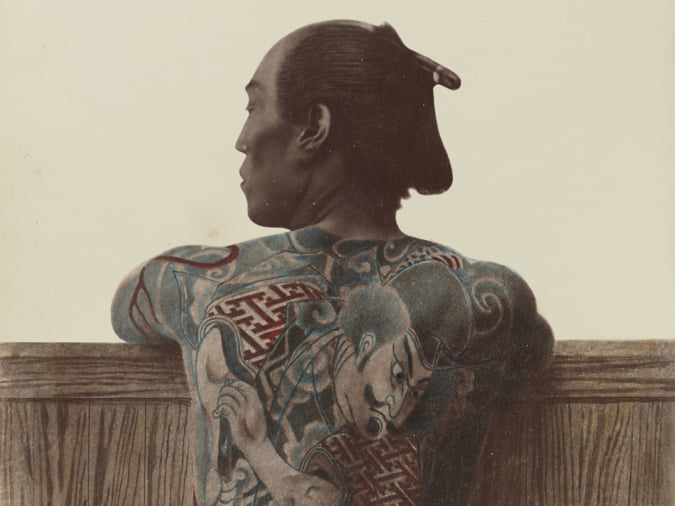

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.