Daisuke Ito, from One World to Another

Japanese photographer Daisuke Ito lived for a long time in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Since his return to Japan, he has been photographing the country’s countless tourist spots. A stark contrast as surprising as it is fascinating.

Harajuku, Tokyo

Hakone, Yokohama Chinatown, the great Kaminarimon gate of Asakusa, the Golden Pavilion of Kyoto or the Tsutenkaku tower of Osaka… So many emblematic touristic places, immediately identifiable by any Japanese person, from the north to the south of the country. Places that have themselves become ‘cliché’, like postcards from souvenir shops. And yet, it was enough to have them photographed by Daisuke Ito to find something strange and new in them. A visual shift born of unexpected details, which have inadvertently slipped into the frame: a baby sitting in front of his iPhone in the foreground of a torii or a Shinto shrine, a couple posing among cherry trees in bloom. Or even a group of bantering foreign tourists proudly carrying a camera. The scene conveys the excitement, the ingenuous enthusiasm of these travellers, as much as it astonishes. Daisuke Ito captures the seriousness and conviction with which foreign visitors photograph Japan’s tourist hot-spots before arranging his pictures as if they were tourist guides themselves.

Shinjuku, Tokyo

After living the ordinary life of a Japanese employee for a few years, he left to study photography in Barcelona. He then headed for South America before settling in a favela in Rio de Janeiro. Released last January, Romântico is the album representing his ten years in the slums of the Brazilian metropolis, spent capturing gangs, prostitutes and favela inhabitants in front of the lens of his camera. His recipe for penetrating these places from below, as little documented as they are dangerous? Uncommon audacity and communicative sympathy. One appearance on Japanese television later, Daisuke Ito made a name for himself, and his work attracted the attention of everyone. Contrast can be questionable. After spending ten years in one of the most violent places on the planet, after having framed the most tense scenes, after having photographed what nobody wants to see, why this series on the most touristic Japanese places, however offbeat it may be? Did he really have to have spent ten years of his life in the most hostile environment to compile the most famous and popular tourist spots in Japan? ‘When I lived in Rio, I was always in the darkest, harshest places and the idea never occurred to me to go and photograph the tourist spots, those where travellers congregate, the Christ of Corcovado for example. Whereas today, I might want to. In the same way, I’m Japanese but I don’t know much about Japan. When I came back to Japan, I wanted to see this country with a pure and naive spirit. That’s what made me want to take pictures of these very exposed, centralised places’.

Nijubashi, Tokyo

To blend in with the crowd, to be just one tourist among the others, all the photos in this series were taken with a smartphone in documentary fashion, in order to show that even if the settings are made so that the tourist monument is as beautiful as possible, it is when the gaze of a third person ‒the tourist‒ appears that the real shooting stars. It is because the behaviour of foreigners in front of a tourist site is different from that of Japanese people that the unforeseen is pointed out, and it is this contrast that interests Daisuke Ito. ‘Thanks to the smartphone, people become inextricable from the landscape. That’s the best thing a photographer can capture. In the favelas, there were things that I couldn’t photograph, because that would have displeased the gangs. How many times did I tell myself that what I was seeing was extraordinary without being able to take the picture! It was very frustrating. Now that I can take my pictures in a relaxed way, it’s quite enjoyable’.

The number of foreign tourists in Japan has been increasing sharply in recent years. Seeing someone photographing a temple, a Zen garden, an architect’s building or taking a selfie in front of a monument is today typical or even banal. For the Japanese people, these are opportunities to discover a new way of looking at their own country, to take a step to the side, in a way. With Daisuke Ito begins a new chapter in the history of street photography in Japan: that of the archipelago at a time of mass tourism.

Hakone, Kanagawa

Yokohama, Kanagawa

Tennoji, Osaka

Yokohama, Kanagawa

Chidorigafuchi, Tokyo

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

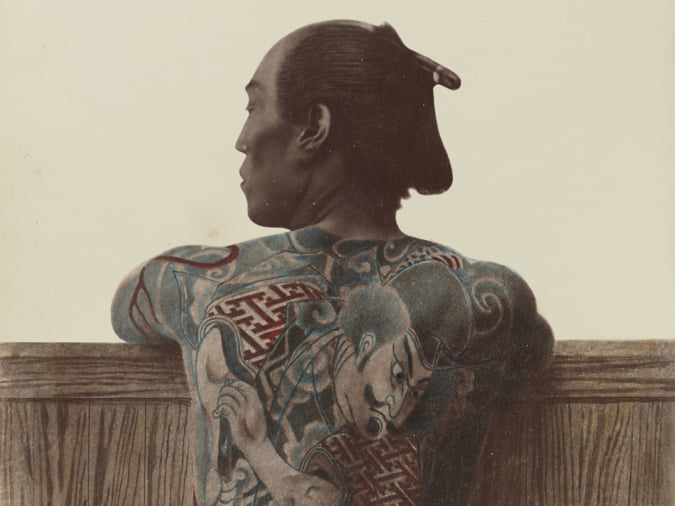

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

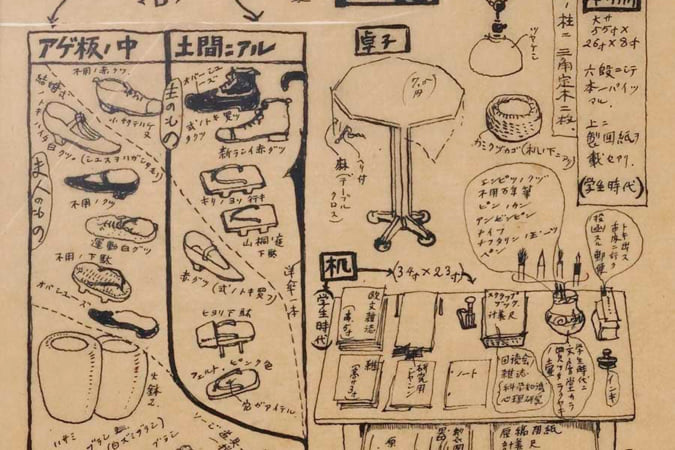

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.