The Day the Emperor Became a Regular Japanese Citizen

In the series 'Sunday at Hirohito's', artist Meiro Koizumi illustrates how images can manipulate the collective psychology.

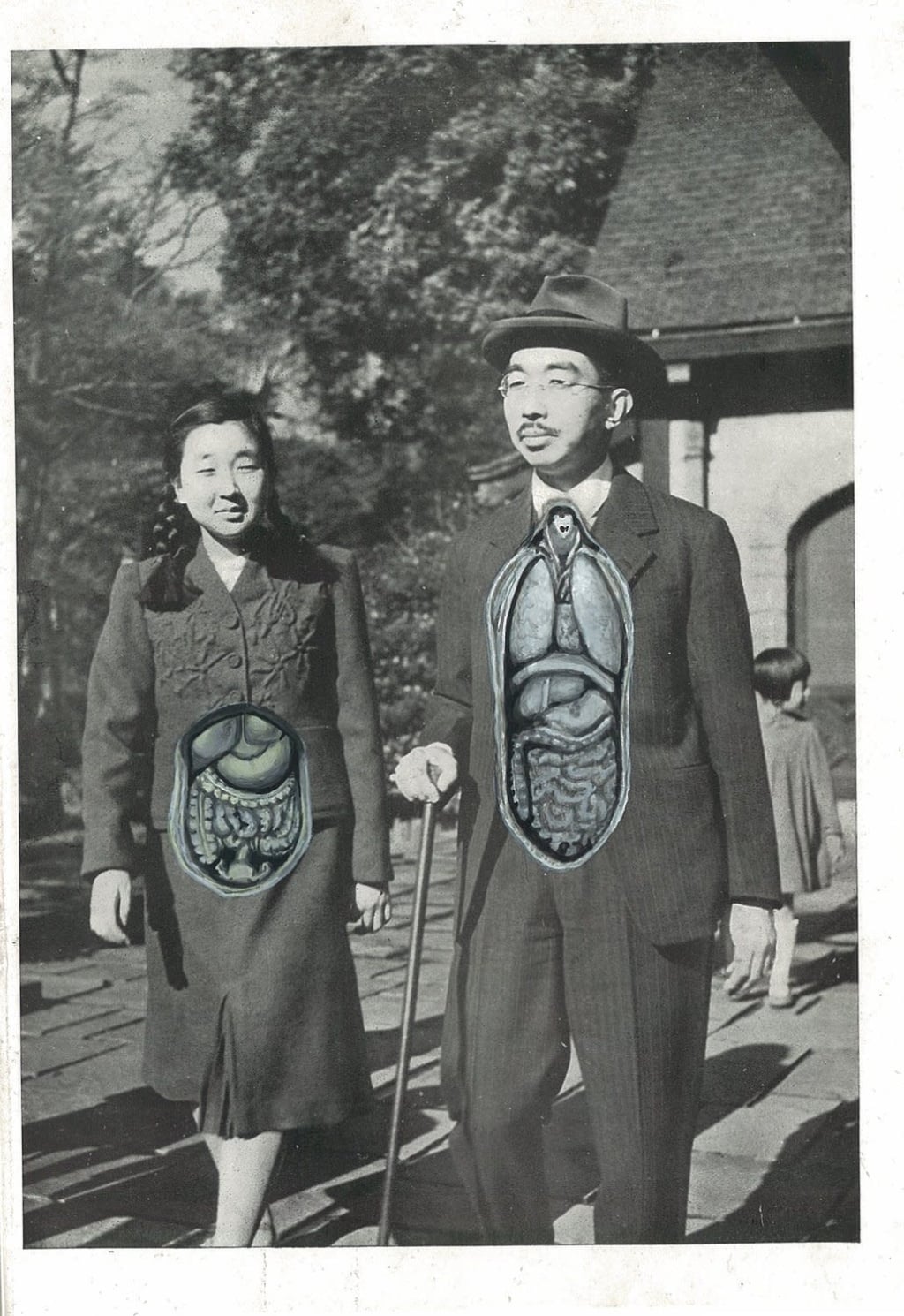

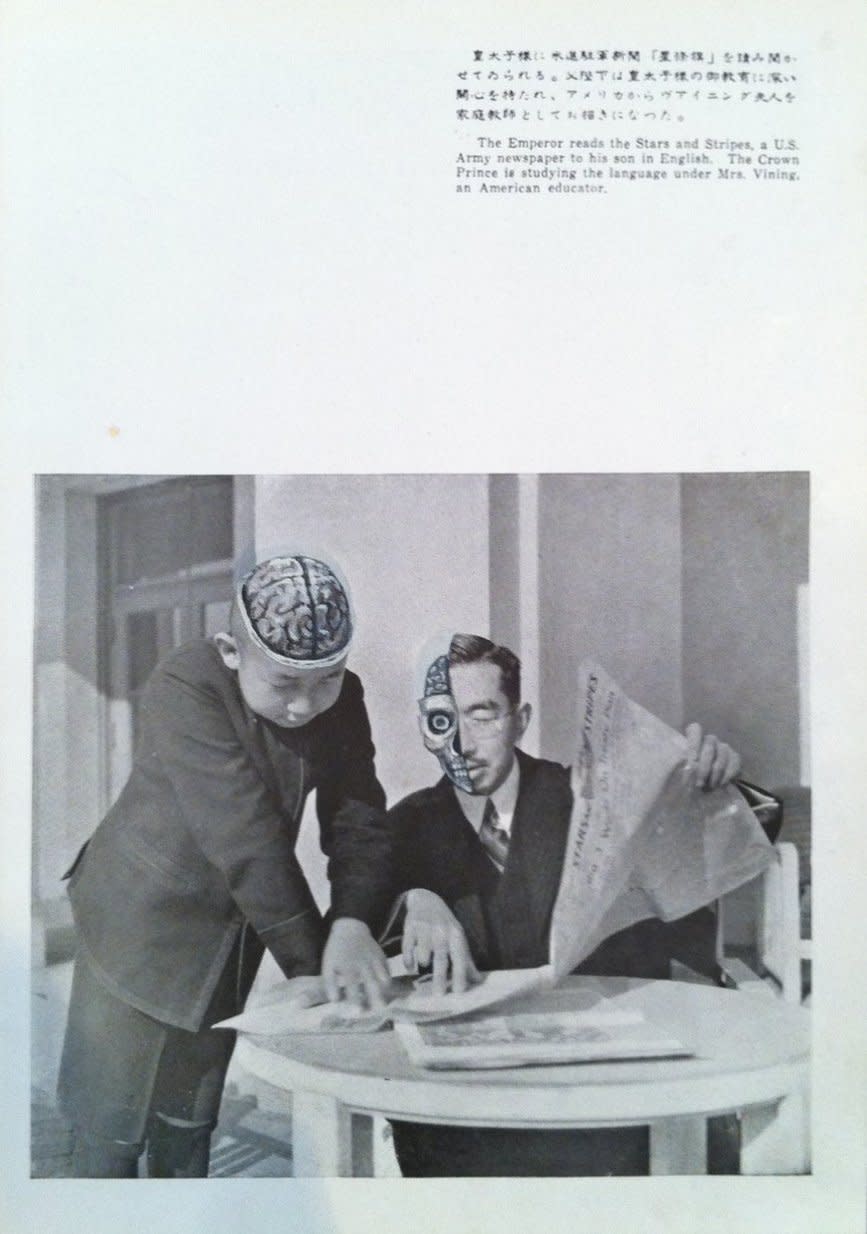

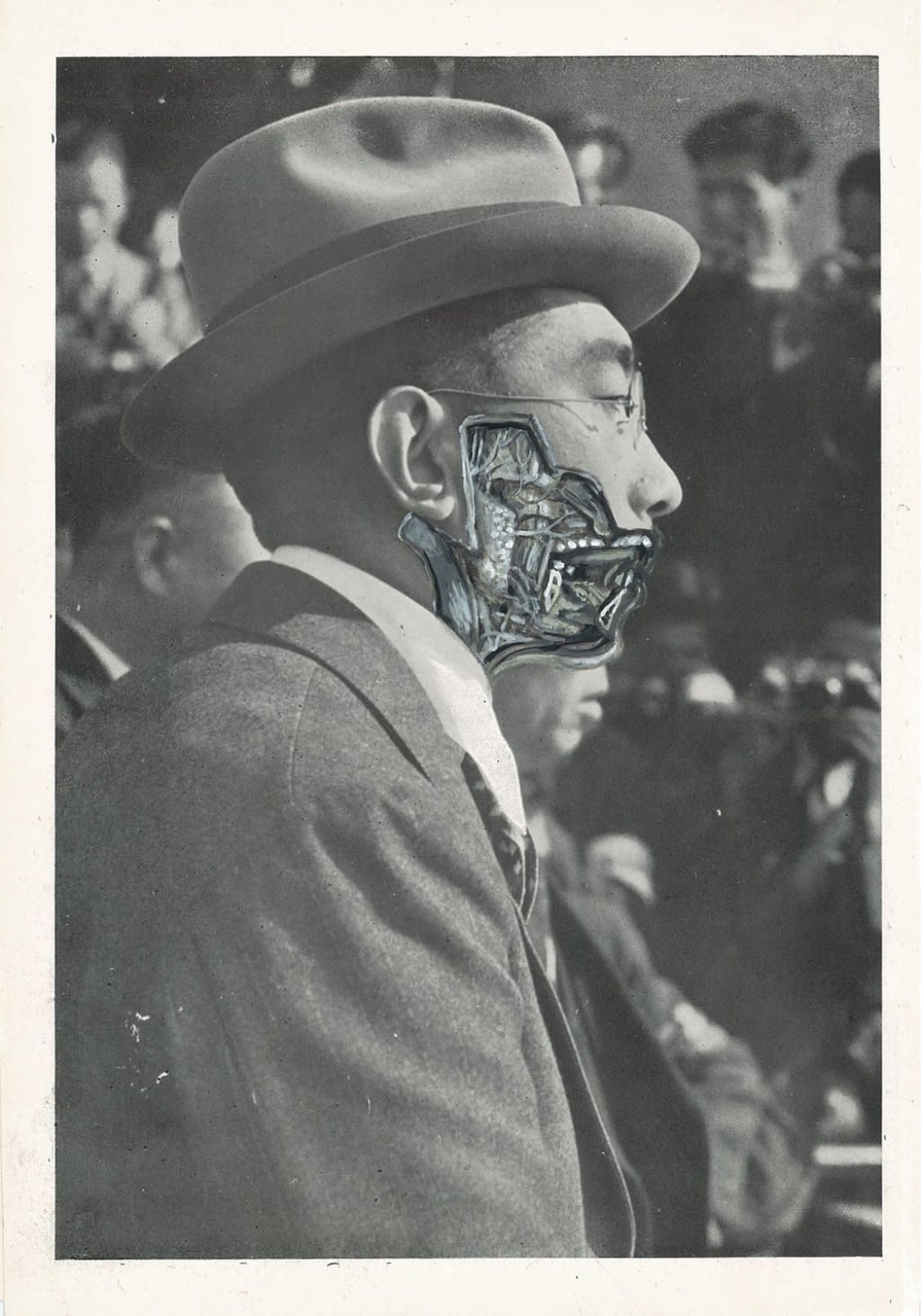

© Meiro Koizumi

Up until the end of the Second World War, the Japanese people had had very few opportunities to see their Emperor. When the conflict ended, after the American victory, the US forces took Hirohito to show himself to the nation, an event documented by the magazine LIFE in a series entitled Sunday at Hirohito’s. This way of presenting the monarch wandering around among the people was the starting point for the work of artist Meiro Koizumi, driven by a ‘desire for iconoclasm’, as he explains to Pen.

Having attended Chelsea College of Art and Design in London and the Rijksakademie of Visual Arts in Amsterdam, Meiro Koizumi is a founding member of the Artists’ Guild, a group of artists who engage in experimental projects.

Becoming aware of one’s relationship with power

In his work, the artist combines a critical eye with a historical and collective conscience, using images to address the sensitive issues in Japanese culture and the collective memory. In this way, Meiro Koizumi examines how visibility and the way the public perceive things influence an individual’s image and status.

Starting from the first photographs showing the Emperor in informal poses, contexts, and environments, for example walking with his family, the artist explores this moment of reversal, when this individual who was considered as superior to humans, godlike, came down from his pedestal to become an ordinary citizen in the eyes of the public. The series Sunday at Hirohito’s (2012) led Meiro Koizumi to take this concept further, with anatomical images ‘stuck’ onto the Emperor’s body.

To gauge the concrete impact of this event and his photomontages, Meiro Koizumi analysed his own father’s reaction. ‘He is a strict Christian, and being Christian to people of his generation means being liberal, which means more or less being anti-tradition, anti-establishment, and anti-Emperor. Ever since I was a child, he always expressed negative emotions towards the Emperor and royal family. So he never considered the Emperor as someone sacred, but always just as a person.’

This vision, however, this relationship to this power hides something less conscious, anchored in the collective imagination, a sort of sensitivity in the face of the representation. ‘When he saw me “playing around” with the image of the Emperor, he felt hurt, but first confused by his own reaction. Then he was disturbed when he discovered that he unconsciously accepted and liked the Emperor all these years. This imperial system operates within people’s unconsciousness, and it sneaks into your system whether you like it or not. This is very much connected with the danger of nationalism’, the artist continues. It’s an appeal to awaken their consciousness, the best guarantee of democracy.

To accompany the series, Meiro Koizumi published the following lines:

All his life, he has rejected the Emperor.

All his life, he has believed in the Christian God.

All his life, he has believed the Christian God was the only God.

Yet, at the age of 76, he found the Emperor within himself…

In practice, the desire for greater transparency of power could pass via the elite in the form of a mirror, in which citizens would see themselves reflected.

Demonstrating another side of the artist’s output, he created a work of sound art entitled AntiDream #2 Torch Ritual Edit in 2021 that addresses the dismissal of the Japanese people amidst the Tokyo Olympic Games.

The artist’s work can be found on his website and on the website for the Annet Gelink gallery who represents him.

© Meiro Koizumi

© Meiro Koizumi

TRENDING

-

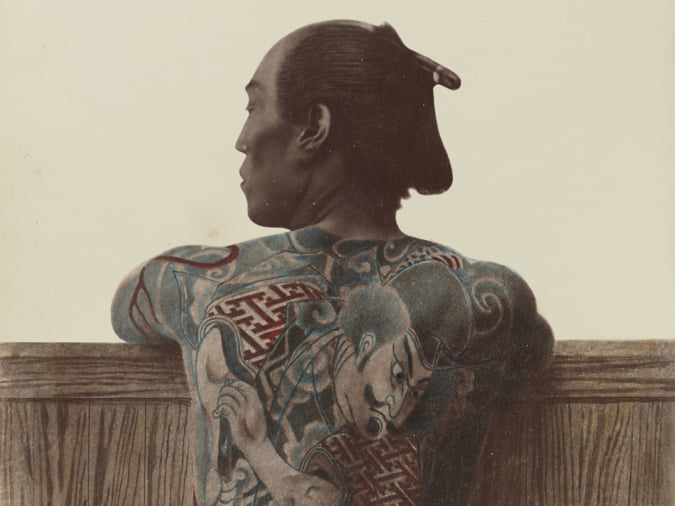

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Fighter Jet-Shaped Mazda RX500 in the Words of its Original Designer

The Mazda RX500 was not a mere show car, but a prototype vehicle, developed as the successor to [the Mazda] Cosmo Sports.

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

Sushi from Nara, Wrapped in a Delicate Persimmon Leaf

Used originally to preserve the freshness of raw fish, this technique has become a staple food from the former imperial capital.