Shinji Aoyama, Creating Cinema from the Margins

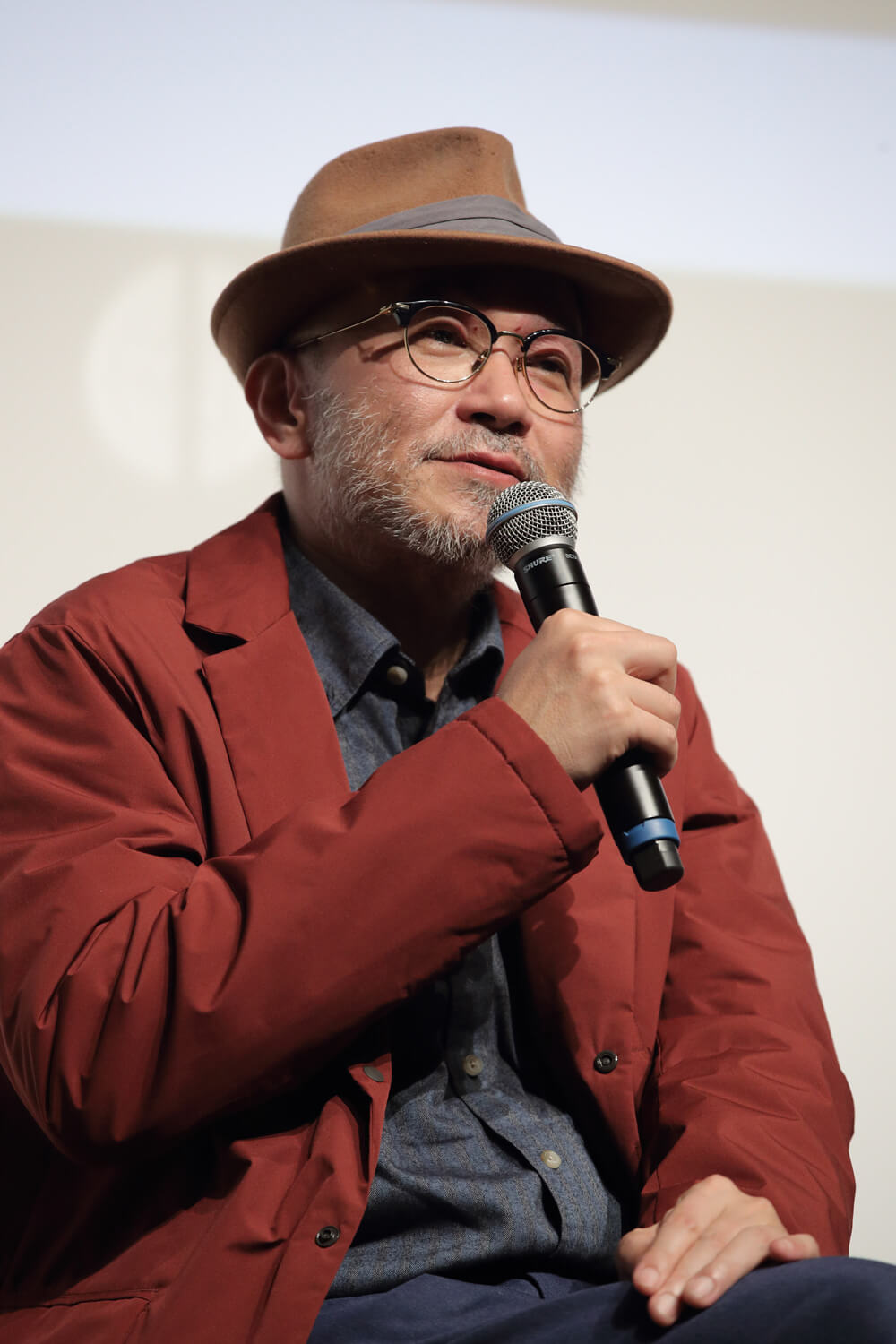

There are few established cinematographers concerned about opening up and sharing their wisdom. This isn’t the case for Shinji Aoyama however who most recently took a five-year break from filmmaking in order to teach film theory at the Tama University of Art.

A few months after his return to the big screen alongside his favourite producer Takenori Sento, he was in Paris for the retrospective ‘100 years of Japanese Cinema’ at the Maison de la Culture du Japon.

‘I feel like a brother to the world of French cinema’

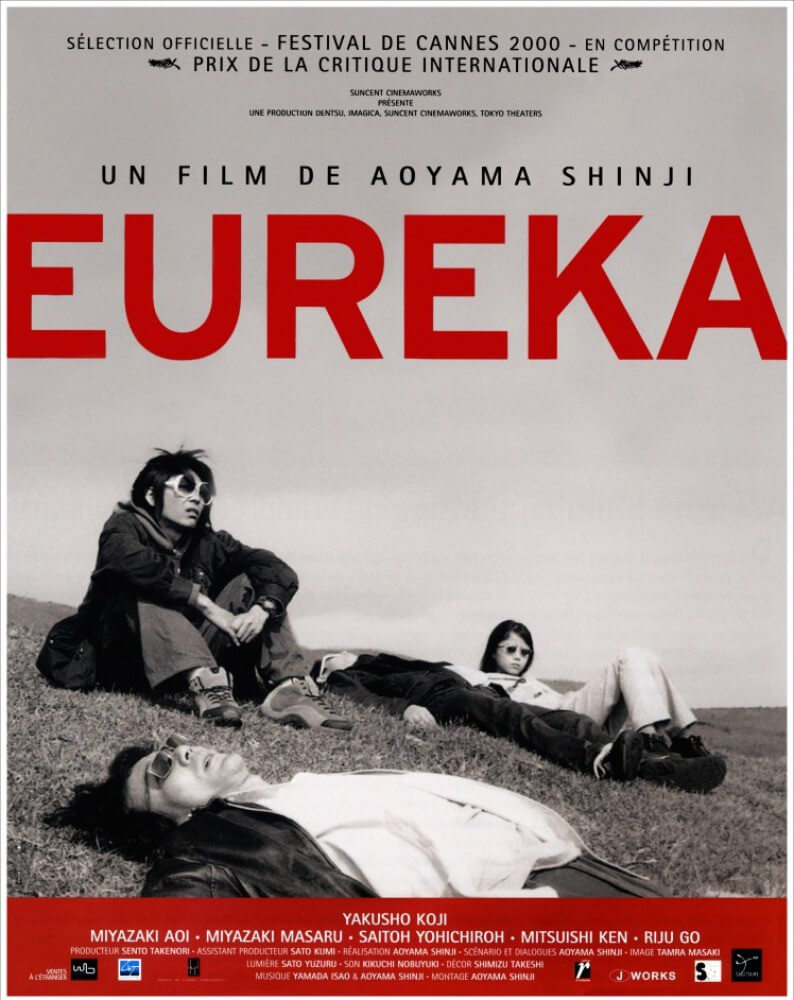

The director participated in a discussion following a screening of his film Eureka. The masterpiece was released in 2000 and won both the Jury Prize and the International Critics Prize at Cannes.

In this black and white film, we follow an epic saga featuring a brother and sister (Aoi Miyazaki) and a bus driver, the only survivors after their bus was hijacked. The story is one of trauma and resilience, which unfolds over more than three hours against a breathtaking aesthetic backdrop.

Eureka is the third episode in a trilogy made in homage to the filmmaker’s native Aoyama, on the southern isle of Kyushu, an area infrequently depicted on screen. In France, he is often remembered however for his more recent Tokyo Park released in August 2012, defined by its use of the fantastic.

Aoyama is widely considered to be the flag barer for the second Japanese New Wave, or the Rikkyo New Wave, after the name of the university where its members studied. Kurosawa, to whom Aoyama was, for a long time, assistant director, is also a prominent member.

PEN sat down with the director and educator to discuss his relationship to cinema and the Japanese scene.

What kind of relationship do you have with French cinema?

The films I make are very influenced by American cinema. However I am nonetheless also very inspired by French film. I feel like a brother to French cinema. I frequently recommend films like Jean Renoir’s Les Règles du Jeu to my students.

Twenty years ago you wrote a manifesto for the Japanese New Wave where you refer to a ‘system’ of Japanese cinematography, by which one must contort oneself in order to be able to distribute their films. You cite for example, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who, from within this system, was able to stand out by manipulating it. Today, what is your view on creating cinema at the margins?

Unfortunately today I am trying to escape Japanese cinema. To my knowledge, there aren’t any recent films that push us to think, and this hasn’t changed in 20 years. I think it is partly from laziness on behalf of those of us who work in cinema in Japan. There is certainly a degree of progress, which we can discern from the increasing number of Japanese directors to win prizes in Japan like Kore-Eda who won the Palme D’or in Cannes, or the recognition afforded to Naomi Kawase. However Japanese cinema still needs to take the next step, and in absence of this, I feel a sort of generalised frustration.

What surprises do you have in store for your next film?

If a film isn’t able to surprise, it’s not cinema. Kiyoshi Kurosawa frequently discuss the fact that in cinema, to be surprised, is a real joy. It is the one element we must preserve.

TRENDING

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

‘YUGEN’ at Art Fair Tokyo: Illumination through Obscurity

In this exhibition curated by Tara Londi, eight international artists gave their rendition of the fundamental Japanese aesthetic concept.