The Living Memory of the Deportation of Japanese-Americans Told in a Graphic Novel

In 1942, George Takei had to leave his home with his family after being summoned by American soldiers who came knocking at their door.

© Fort Rohwer 1942 - Wikimedia Commons

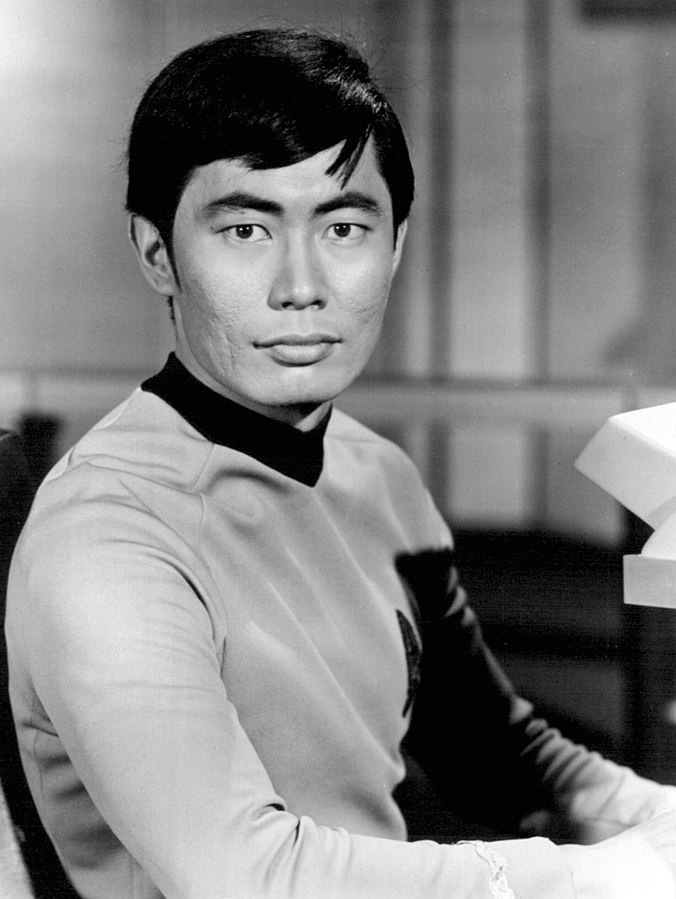

Famed for playing Captain Hikaru Sulu in Star Trek, George Takei is above all an American with Japanese ancestry. While his roots brought him fame and fortune because they allowed him to push open the doors of Hollywood, they were not always synonymous with luck in his life.

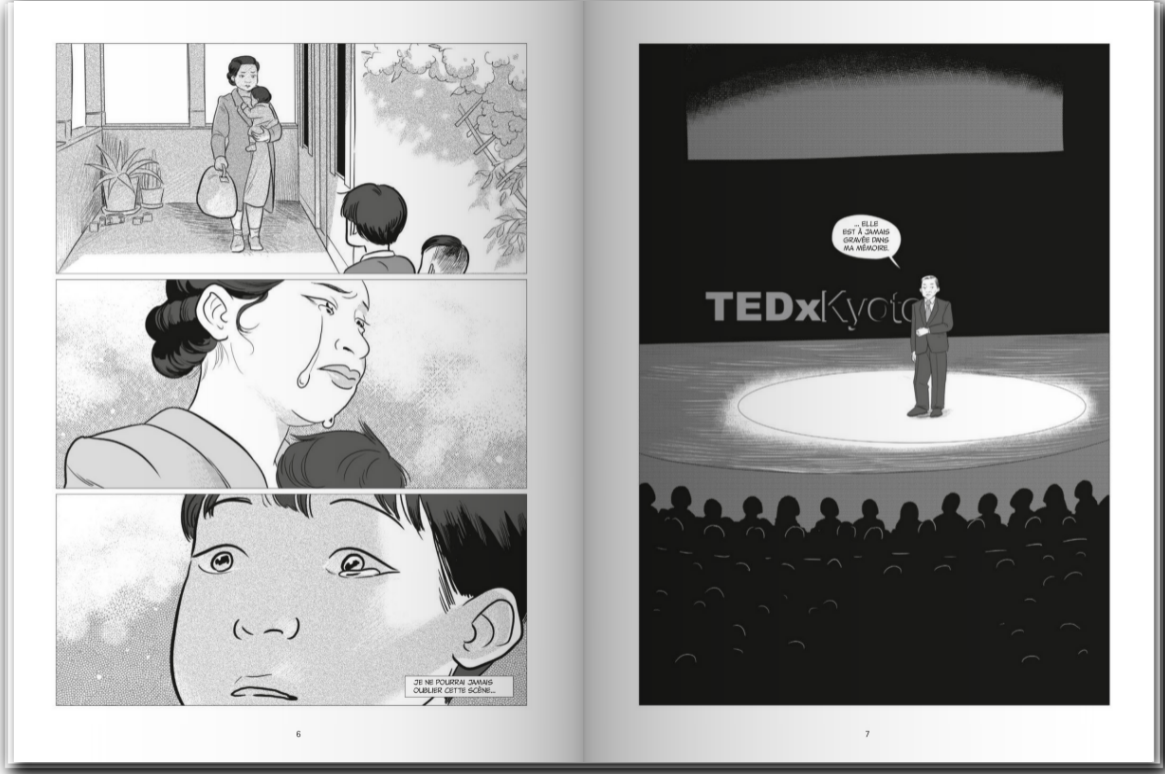

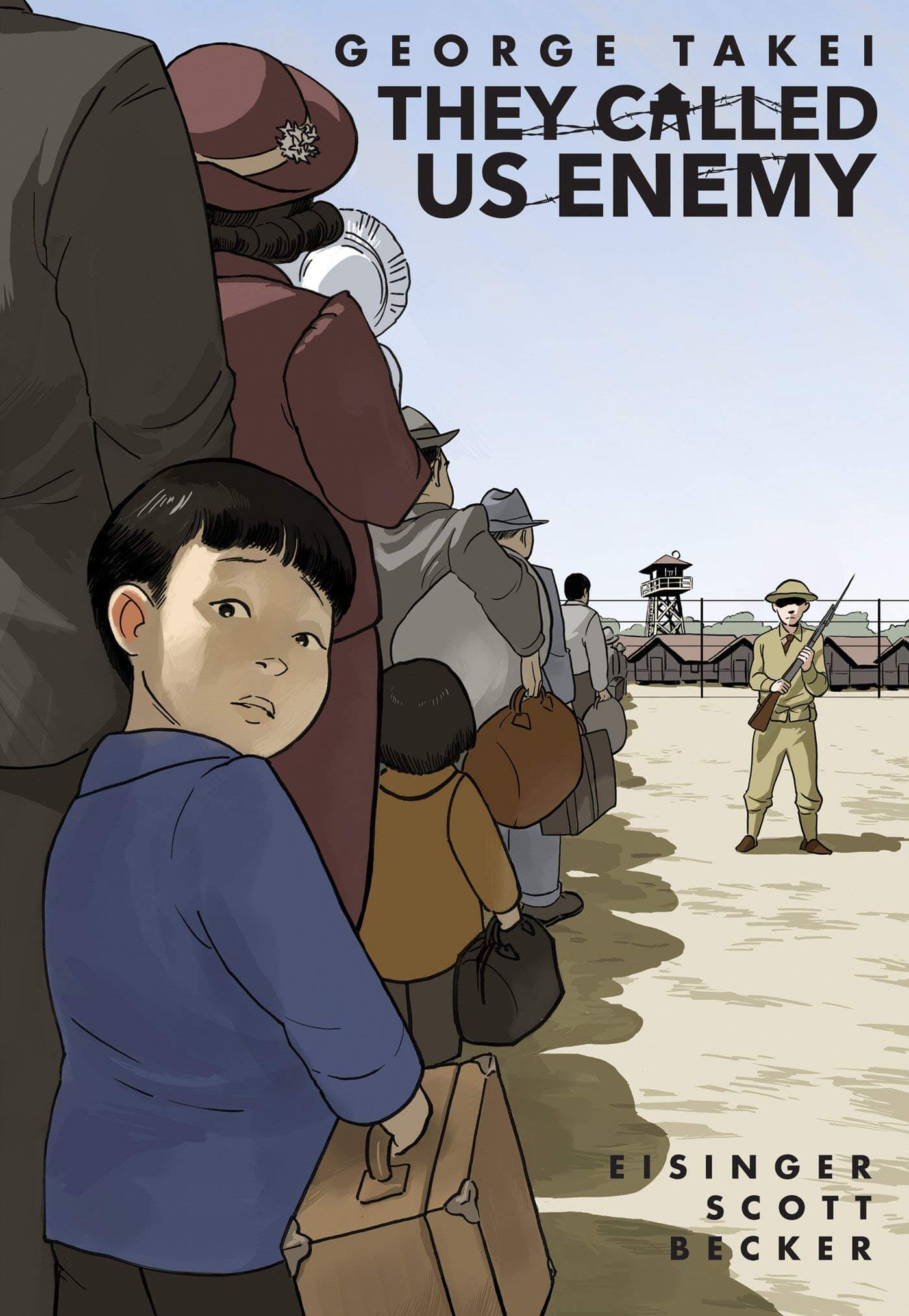

In the graphic novel They Called Us Enemy, published by Random House in 2020, he tells of a little-known chapter in American history: the confinement in ‘relocation’ camps of Japanese people and Americans of Japanese origin in the United States, ordered by the government just after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

‘The Japanese race is an enemy race’

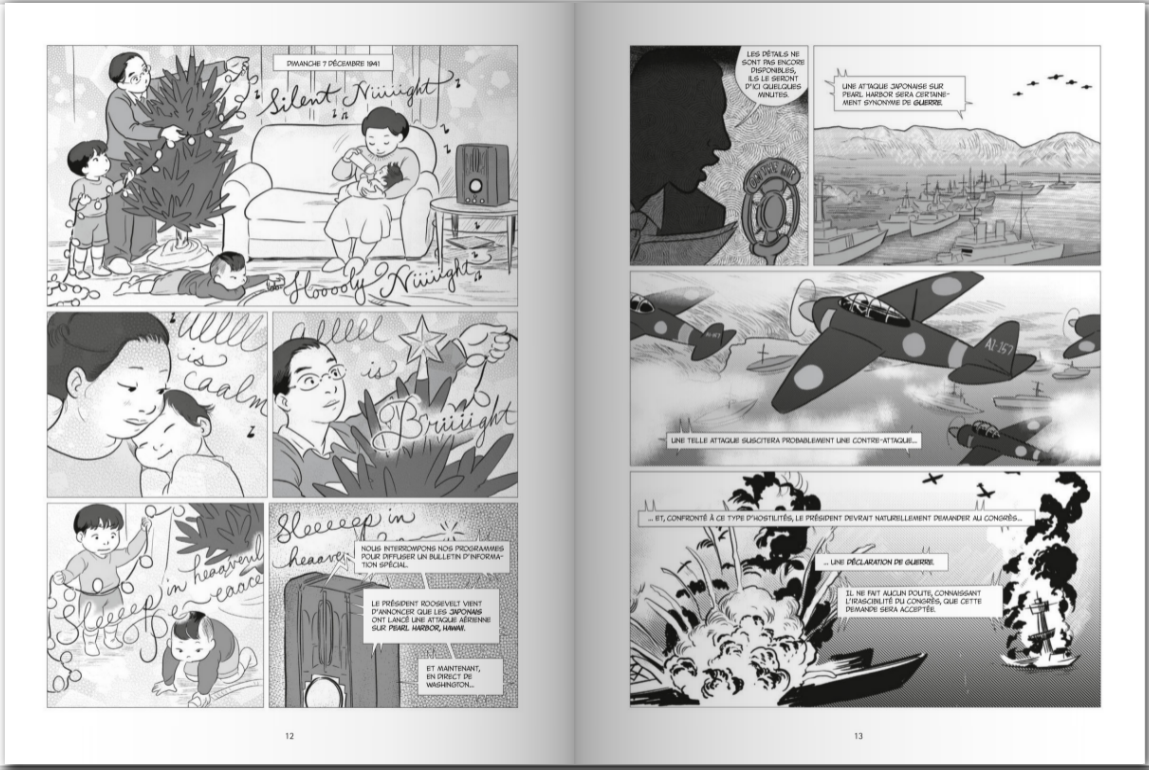

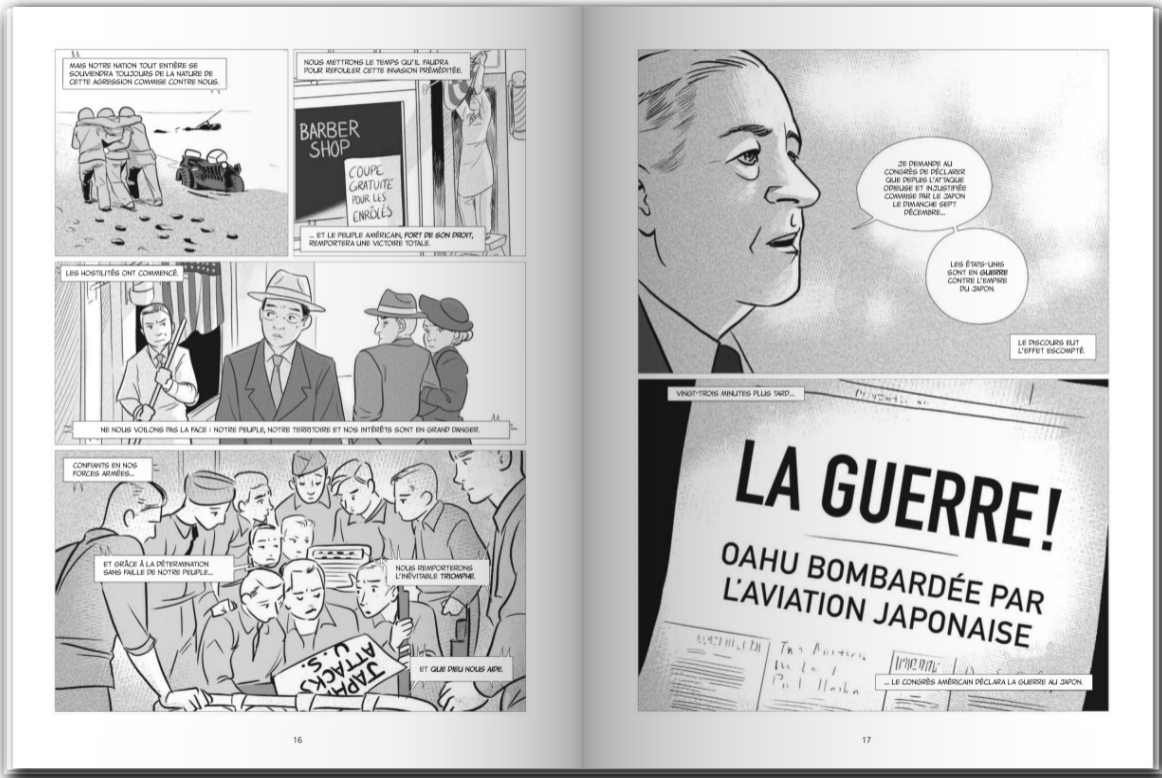

On 8 December 1941, President Roosevelt declared war on Japan in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor the day before. As a result, a strong anti-Japanese sentiment was established in the country. The west coast, under the initiative of General John DeWitt, was first to organise for some of its residents to be deported if they were of Japanese origin from February 1942 onwards. Although the general initially explained that he wanted to protect this population from the hatred of white Americans, he ended up showing his true motivation when he declared: ‘the Japanese race is an enemy race and, while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized’, the racial strains are undiluted’. The American government and armed forces feared a hypothetical allegiance to the Japanese emperor, and mercilessly launched a campaign of brutal persecution.

George Takei’s family, who lived in Los Angeles in California at the time, had to leave their home and laundry business overnight with a few suitcases and three children. Along with thousands of others, they were boarded onto trains and taken by force to austere, squalid barracks surrounded by barbed wire, hastily built in inhospitable areas. The camp that the Takei family went to was located in Arkansas and named Fort Rowher. Later, they were sent to Camp Tulelake in California.

In the graphic novel, George Takei tells of how he, his brother and their friends, like many other children, didn’t understand what was going on: they thought they were going on holiday. But reality soon hit them, because the living conditions were extremely harsh in the camps. Many people got ill, were malnourished or were exhausted by the work imposed on some of them. It then became impossible to turn a blind eye to the violence, when those who looked as if they were going to try to escape were shot by the soldiers from the watchtowers without further ado. For four years, the young George endured these conditions and understood that, for no justifiable reasons other than their appearance, he, his family and his friends had become enemies in their own country.

Race prejudice and war hysteria

Indeed, ‘race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership’ were recognised by President Jimmy Carter in 1988 when he apologised to the survivors. In this period troubled by war, the anti-immigration sentiment towards people of Asian origin that already existed in the USA only became stronger. When they were deported, most Japanese families and American families of Japanese origin lost everything: their homes, their possessions, their businesses. The reason for their lack of resistance was shikata ga nai (‘nothing can be done about it’): the strong spirit of resilience that they had developed over the course of wars lost and the period of foreign rule in their country of origin.

Not wanting to make waves, most of these families obeyed the government’s unjust injunctions dutifully and did not demand any compensation after they were freed. The majority of them remained in the United States, like George Takei’s family, and, rather than rise up against the oppressive government, many tried to ‘redeem [their] name and uphold [their] honour’ (declaration made by Daniel Inouye, then-future senator who was a member of the highly decorated 442nd US Army Regiment, made up of Japanese-American volunteers, quoted in the graphic novel), preserving their lineage on American soil and avoiding passing on the painful memories of confinement to their children and the following generations.

George Takei went through two states of mind over the course of his life: first humiliated, he did everything he could to integrate in his home country once more and went on to become the famous Hollywood actor we know, humbly accepting the sometimes stereotypical and degrading racial characteristics that surrounded the only roles he was given. However, in the second part of his life, he undertook to use his voice to firmly denounce the violent acts of which he and his people were victim, perpetuating an essential duty of remembrance, ignoring the discretion of the Japanese and Americans of Japanese origin, and the national amnesia, partners in this tragic story.

They Called Us Enemy (2020), a graphic novel by George Takei, Steve Scott and Justin Eisinger published by Random House.

© “Nous étions les ennemis”, 2020 - éditions Futuropolis TDR

© “Nous étions les ennemis”, 2020 - éditions Futuropolis TDR

© “Nous étions les ennemis”, 2020 - éditions Futuropolis TDR

© Fort Rohwer 1942 - Wikimedia Commons

© George Takei - Wikimedia Commons

© ‘They called us enemy’ — George Takei

TRENDING

-

Hiroshi Nagai's Sun-Drenched Pop Paintings, an Ode to California

Through his colourful pieces, the painter transports viewers to the west coast of America as it was in the 1950s.

-

A Craft Practice Rooted in Okinawa’s Nature and Everyday Landscapes

Ai and Hiroyuki Tokeshi work with Okinawan wood, an exacting material, drawing on a local tradition of woodworking and lacquerware.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

‘Shojo Tsubaki’, A Freakshow

Underground manga artist Suehiro Maruo’s infamous masterpiece canonised a historical fascination towards the erotic-grotesque genre.

-

‘Seeing People My Age or Younger Succeed Makes Me Uneasy’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.