Toru Takemitsu’s Liquid Orchestra

‘Takemitsu: 1982 Historic Recordings’, a live album of Japan’s important classical composer, commemorates 25 years since his passing.

‘Toru Takemitsu: 1982 Historic Recordings’ (2021). Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

In ‘A Way Alone II’ and ‘Dreamtime’, sounds are built up by the Sapporo Symphony Orchestra, only to be left hanging afloat. Strings, flutes, and harps recede in and out in ‘Towards the Sea’, pausing in between dark silences. Guided by Toru Takemitsu, Japan’s most famous composer, who previously troubled the self-assuredness of Western classical music, audiences move alongside liquid compositions and fluctuating sceneries.

In Takemitsu: 1982 Historic Recordings, out on Deutsche Grammophon, the entire recording of a special concert that took place on June 27th, 1982 is released for the first time to commemorate his work 25 years since his death in 1996. It was a legendary event, taking place alongside this renowned orchestra and the highly-regarded conductor Hiroyuki Iwaki, but for composer Toru Takemitsu it also documents a critical point his career. The album crucially includes a speech by Toru Takemitsu made on this particular evening, where he explains his philosophy of music through water. Like the many currents that are hidden underneath a single lake or ocean, to him the total nature of music—with all of its infinite streams of influence from across the world—has the same indeterminate fluidity.

Hearing Beauty in Impermanence

A largely self-taught composer and prolific writer, the internationally renowned Toru Takemitsu bridges elements of East and West in his aesthetic. While manipulating the tonalities of classical music according to timbres of traditional genres like gagaku, he infuses their established structures with Oriental philosophy and radically instills elements of silence within. Toru Takemitsu’s cultural contributions are further indisputable in his work soundtracking films, having worked on over 100 in four decades—these include Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1964), Nagisa Oshima’s Empire of Passion (1978), and Akira Kurosawa’s Ran (1985).

The beginnings of Toru Takemitsu’s career in the 1950s shared the ambitions of an international avant-garde, when artistic movements were aiming to collapse pre-existing cultural frameworks in a post-war context. As a founding member of Japan’s avant-garde workshop Jikken Kobo, Toru Takemitsu’s own visions developed upon a backdrop of rigorous sound experiments—including those in electro-acoustics, conceived simaltaneously by Pierre Schaffeur’s musique concrète. The cross-cultural philosophy of Fluxus composer John Cage was a particular influence for Toru Takemitsu, as he explains in his speech, since an infinite world of sounds flowed into his music once silence itself was raised as a powerful resonance.

In his life, Toru Takemitsu had sought out a palpable metaphor for the shape of music and found only a misty impermanence. Each and every sound, however many times repeated or recognised, has its own distinct and complicated qualities in its moment. Describing when he had first learnt that birds never sing the same song twice, he reminds us that the fundamental beauty of sound lies in its transience.

Takemitsu: 1982 Historic Recordings, is available on Deutsche Grammophon. A selection of his discography can be viewed below.

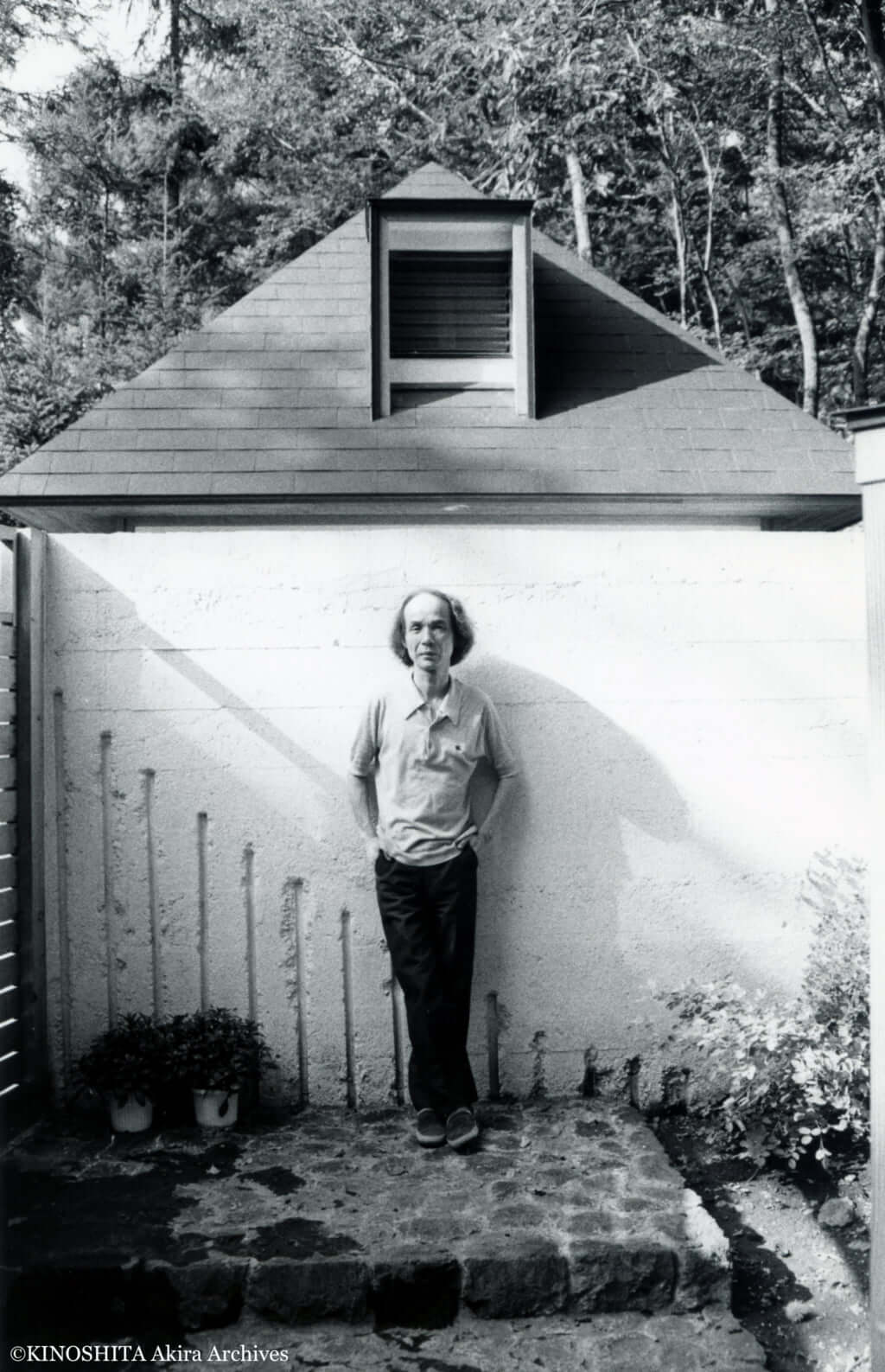

Portrait of Toru Takemitsu. Courtesy of KINOSHITA Akira Archives / Deutsche Grammophon.

‘Miniatur II : Art Of Toru Takemitsu.’ (1973) Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

‘Miniatur III Art Of Toru Takemitsu.’ (1972-1973).

‘Minatur V:Art of Toru Takemitsu.’ (1975) Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

‘In an Autumn Garden for Gagaku.’ (1975) Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

‘Quatrain / A Flock Descends Into The Pentagonal Garden.’ (1980) Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

‘Quotation of Dream.’ (1991) Coutesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

‘I Hear The Water Dreaming.’ (2000) Courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

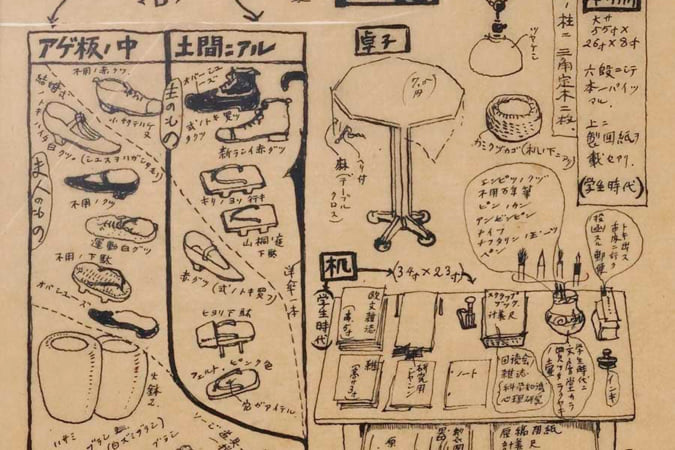

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

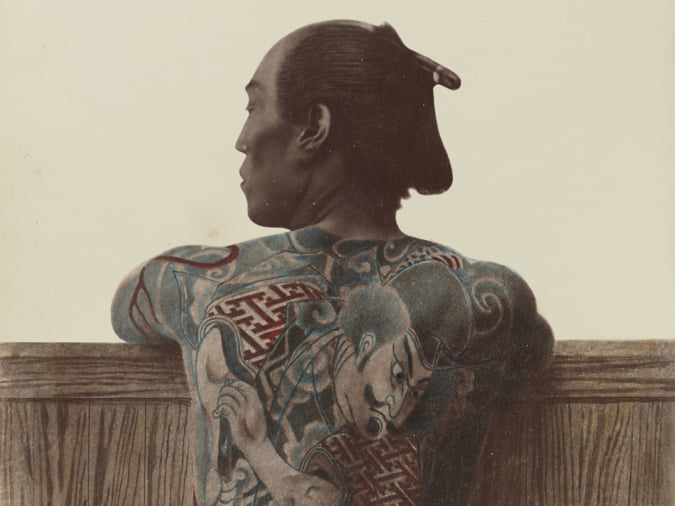

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.