Kawai Kanjirō’s House-Museum, A Hidden World of Craft in Kyoto

A former home and studio filled with wood carvings, handcrafted furniture and ceramics from a pioneer of the Mingei movement.

Fashion reporter and photographer Kazushi Takahashi turns his gaze beyond the runway, tracing the beauty that lives in the everyday. A graduate of Meiji University and Bunka Fashion College, he began his career as an editor at Bunka Publishing Bureau (MR High Fashion, Soen). Now freelance, he travels through Japan to write, photograph and style stories where fashion meets craft, design and culture, sharing what he discovers in each issue of Pen.

© Kazushi Takahashi

Introduction

Homes where artists both lived and worked often radiate a powerful creative energy.

So what happens when that power is deeply connected to traditional Japanese culture and the way people once lived?

And what if one of the leaders of the Taishō-era Mingei movement built his own residence, guided solely by his personal sensibility?

Imagine if every part of that home, from the building itself to the storage furniture, chairs and lighting, were designed by the artist.

Wouldn’t you want to visit such a rare space?

Here in Kyoto, the Kawai Kanjirō Memorial Museum is exactly that kind of extraordinary world.

A home where everyday realism and fantasy coexist.

© Kazushi Takahashi

I visited it for the first time in November of this year (2025), and found myself overwhelmed, thinking, ‘I had no idea Kyoto had something this incredible.’

Any sense of ‘museum seriousness’ suggested by the word memorial vanished immediately, replaced by pure fun as I wandered through the rooms.

Kawai (last name) Kanjirō (first name) was a ceramic artist active from the Taishō to the Shōwa period, known for works featuring vibrant colors.

Alongside figures like Sōetsu Yanagi, he helped promote the Mingei movement.

He was also nominated for the titles of Living National Treasure and for the Order of Culture, but declined both.

To be honest, my reason for visiting the museum was not a deep interest in Kawai himself or even in ceramics.

I simply wanted to see a traditional Kyoto house after coming across photos of the interior while researching sightseeing spots.

Nothing more than that.

Yet as I moved through the house and garden, that simple curiosity turned into a series of discoveries and moments of excitement.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

The House

The main contents of the museum include the two-story house built in the Taishō period (from the same era as Kyoto’s machiya townhouses), ceramic works, tools used in production and the remains of a climbing kiln (nobori-gama).

The entire space, from the home to the artworks, is united in such a way that you feel as if the artist might still be living there.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

Most of the lighting seen above, much of the furniture, the house itself and even the wood carvings were all created by Kawai.

Calling them ‘designs’ feels too simple.

They are original works made with the cooperation of cabinetmakers and woodworkers.

It seems that Kawai rarely sold the sculptures he began making in his later years.

Only his ceramics were produced as a livelihood.

That may explain why so many sculptures remain here.

Of all the objects in the house, the ones that captivated me most were those wood carvings and the somewhat African-looking chairs.

© Kazushi Takahashi

Living Sculptures and Chairs

Scattered throughout the house are sculptures that seem to pulse with life.

They remind me of the zashiki-warashi, mischievous spirits said to inhabit old homes.

Here, they truly feel as though they live in the building.

Displayed in a modern gallery, Kawai’s carved figures might lose some of their force.

They appear to draw from traditional Japanese forms such as Buddhist statuary, folk crafts, netsuke and the everyday objects of common people.

To me, however, their unusual presence felt akin to wood carvings from Papua New Guinea (near Indonesia) or African masks.

It was as if they traveled across the sea from some distant land to Japan and ‘naturalized’ themselves.

Seeing how well these characters blended into a traditional Japanese interior was an unforgettable experience.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

What drew me in even more than the sculptures were the chairs, carved and rounded by hand from solid wood.

These too were designed and collected by Kawai for his own use.

Among the chairs in the house is a Spanish craft piece known as the ‘Van Gogh chair.’

There is also a chair hollowed out from a mortar that looks just like an African stool.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

Now, I carry a major personal insecurity.

Working in fashion, I often feel out of place because I lack interest in high-end designer chairs and interior goods.

Even when I can intellectually recognize something as good, my heart does not always respond.

(Although there are exceptions.)

Yet African masks and wooden chairs always lure me in irresistibly.

The problem is that I rarely feel comfortable in ethnic-style spaces.

I like only the objects, not the contexts in which they are presented.

Meanwhile, I am deeply in love with Kyoto townhouses, temples and shrines.

I was never able to reconcile these conflicting tastes.

But visiting the Kawai Kanjirō Memorial Museum, where Japanese architecture and (my imagined) African forms coexist in perfect harmony, something clicked.

The chairs, furniture and carvings feel as if natural materials were brought indoors in their raw state.

Their presence differs entirely from Western aesthetics that reshape nature, such as marble interiors or finely bent wood chairs.

This house is full of breathing life.

The idea of Mingei may seem uniquely Japanese, yet its appreciation of everyday beauty may actually be shared with Asia, Africa and other regions of the world.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

There is an area where you can see photos of the artist sitting at work in this very place.

His desk and chair are small, charming and warmly alive, almost like creatures themselves.

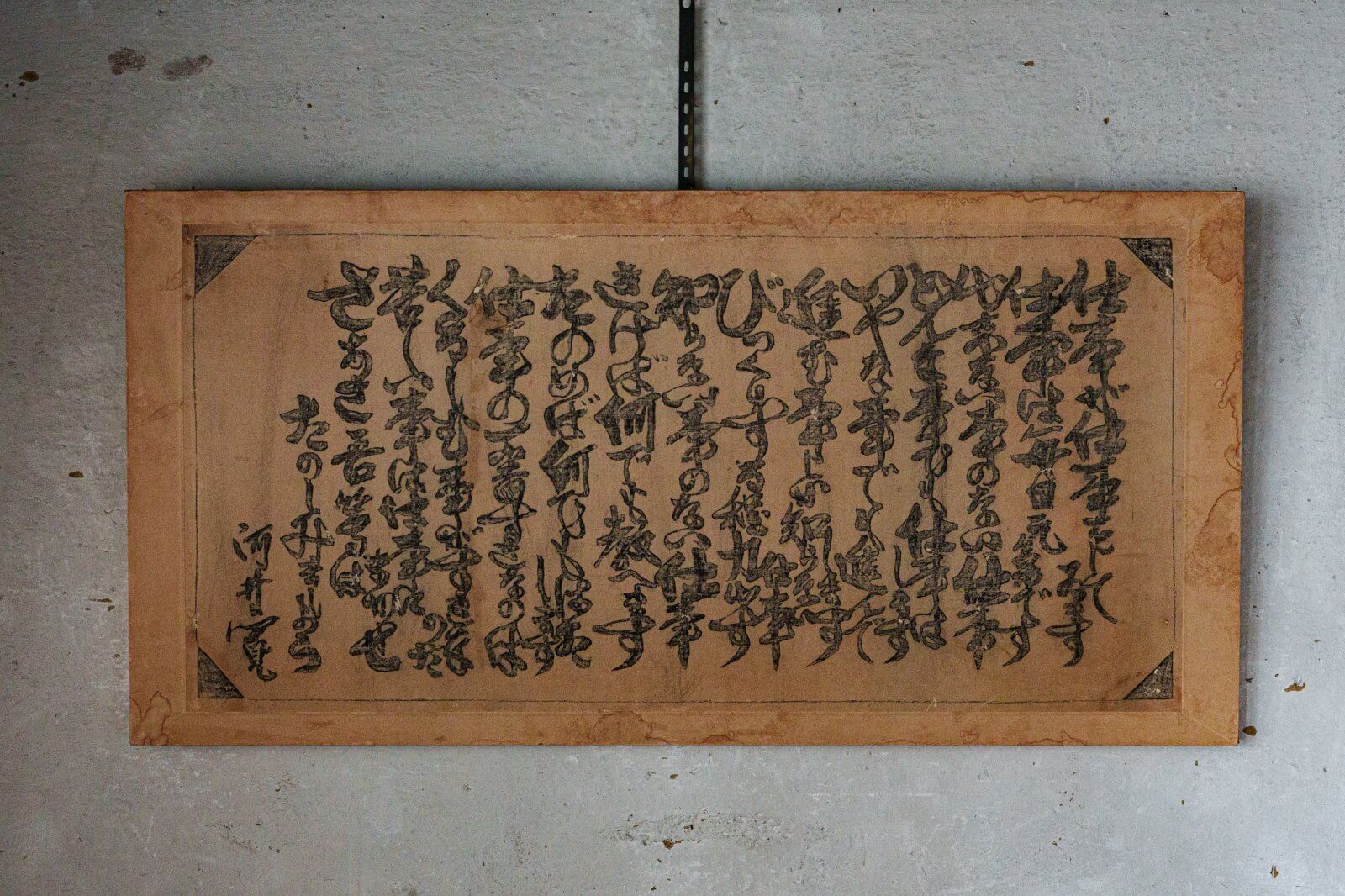

Do not miss the woodblock prints of Kawai’s poetry hanging on the wall.

Here is the poem in full:

Work is doing its work.

Work is healthy every day.

Work has nothing it cannot do.

Work will tackle anything.

Even unpleasant tasks, work takes up willingly.

It knows only how to move forward.

It draws out astonishing strength.

There is nothing work does not know.

Ask, and it will teach you anything.

Rely on it, and it will accomplish anything.

What work loves most

is struggle.

Leave hardship to work

and let us enjoy ourselves.

A remarkable poem that answers the universal question, ‘What is work?’

It speaks to everyone, not just creative professionals.

Another striking line from Kawai is:

‘I want to see a new version of myself — that is why I work.’

It beautifully summarizes the unexpected discoveries and joy that follow sincere commitment.

When we work reluctantly, the mood stays heavy, but when we face it head-on, work can transform into play and lift the heart.

A total shift from negative to positive.

Looking at old photos, it seems that something different once hung here.

It is unclear whether Kawai changed it himself or whether it happened after the house became a museum.

© Kazushi Takahashi

The Climbing Kiln

At the back of the house lies the remains of the kiln Kawai used to fire his ceramics.

A traditional slanted climbing kiln.

© Kazushi Takahashi

© Kazushi Takahashi

There is one more insecurity I must confess.

I am simply not drawn to tableware.

It troubles me, because in the fashion world it is assumed that everyone loves ceramics.

High-fashion brands run craft exhibitions featuring pottery, and gallery shows rooted in ceramics are common.

My eyes simply do not know how to assess the beauty of Kawai’s bowls or plates.

So I did not take any photographs of his ceramics at all.

Instead, I photographed a lineup of postcards showing his works.

Anyone interested should delve deeper on their own.

© Kazushi Takahashi

The Kawai Kanjirō Memorial Museum can absolutely be a primary reason to visit Kyoto.

It is a space where you can experience both ‘Japanese tradition’ and ‘individual creativity.’

Even during the crowded autumn season, when tourists flood places such as Arashiyama and Ginkakuji, I found the atmosphere calm.

The overseas visitors I saw all behaved with care and respect.

On the rare occasions when things got noisy, it tended to be Japanese aunties rather than foreigners, amusingly enough.

Located on the east side of Kyoto, it is a ten-minute walk from Kiyomizu-Gojo Station on the Keihan Line, tucked within a residential area next to modern developments.

Please do enjoy a Kyoto experience here that rivals the greatest temples and shrines.