Niki Nakayama, the Chef Introducing California to Kaiseki

©Zen Sekizawa

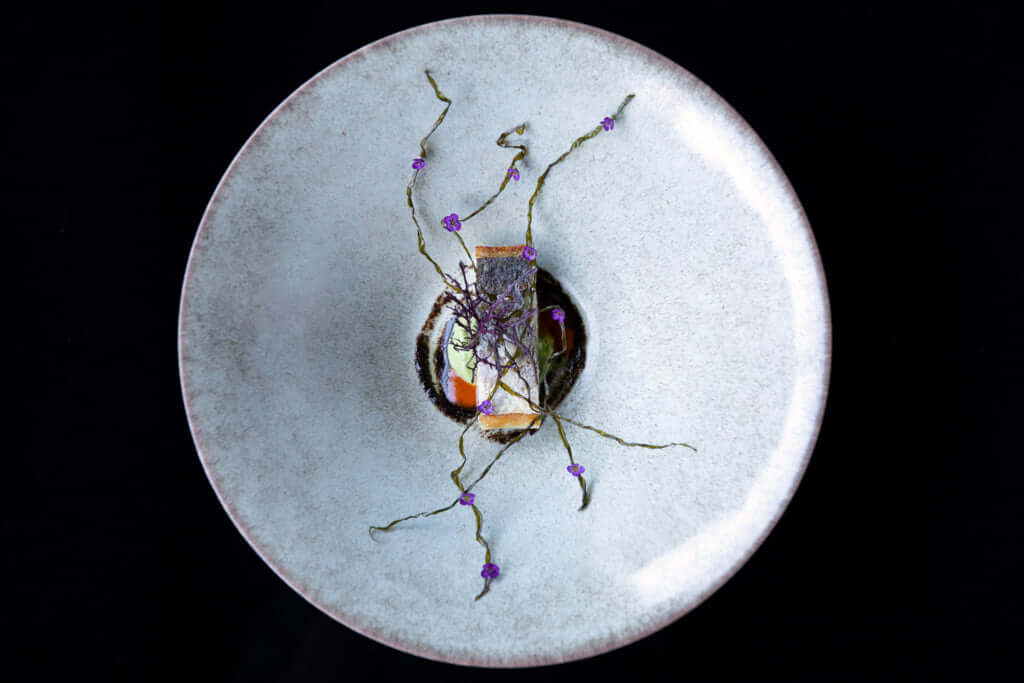

Her dishes are so delicate that you don’t want to touch them for fear of ruining them. However, the freshness of the ingredients used to make them and the ingenious combinations of flavours are unmissable. Chef Niki Nakayama was committed to adapting the very best of what grows in the Californian sun to fit the centuries-old rituals of kaiseki.

This ceremonial cuisine, which involves a dozen carefully crafted little dishes that showcase a particular flavour, lends itself rather well to highlighting pink radishes, lettuce, chard and tomatoes from n/naka‘s organic garden.

The intimate restaurant with just 26 covers is found in Palms, a neighbourhood west of Los Angeles, and has just been awarded two Michelin stars, the maximum an establishment can receive in Los Angeles on the Michelin guide’s debut in California. This is a real accolade for Nakayama. The public support reinforces this, and every week, when new reservation slots for bookings up to three months in advance open on Sundays at 10 a.m. local time, they sell out in minutes.

A California native, Niki Nakayama trained alongside sushi chefs in the United States before carrying out an apprenticeship in 1997 with Masa Sato, chef at Shirakawa-Ya ryokan in Niigata prefecture in Japan. On her return to Los Angeles, she first opened a sushi bar, Azami Sushi Cafe, in 2000, before tiring of her clients’ demand for unnatural fusion cuisine. Kaiseki was calling to her, and she founded n/naka in 2011.

Nothing is left to chance in this restaurant, the details of which Nakayama planned for two years. At first, she wanted a kitchen that was open onto the dining area and attached to a counter, but the Department of Health refused. Instead, she presides over the kitchen hidden behind shoji screens set on sliding tracks, alongside sous-chef Carole Iida, who’s also her wife.

The Japanese welcome, omotenashi, is taken to the next level at n/naka, where details of every diner, from their tastes to their reactions to dishes, are recorded. All of this is done in order to be able to offer them a different menu on their next visit. When service is over, Nakayama pushes back the sliding screens, a symbol of the separation of two worlds, the dining area and the kitchen, and greets every table individually and with humility.

‘The ingredients are more important than you, the cooking is more important than you’, Nakayama tells the New Yorker. ‘Everything about the food is more important than you, and you have to respect that’.

To glorify her products, Nakayama doesn’t hesitate to make a few departures from tradition. This is true for the Shiizakana, the only dish that’s continually on the menu, where spaghetti alla chitarra emerge from a creamy ragu of abalone liver and pickled cod roe dusted with black Burgundy truffles.

Purists will bristle for other reasons. Just the presence of a woman in the kitchen is still considered sacrilegious in Japan. Fortunately, however, an increasing number of women are grasping the status of itamae. Chef Nakayama is, however, possibly the first woman to have dared to open her own kaiseki restaurant. Her twenty-strong, mainly female team (there are 7 men and 13 women, including pastry chef Gemma Matsuyama) has already won over the people of Los Angeles.

©Zen Sekizawa

©Zen Sekizawa

©Zen Sekizawa

©Zen Sekizawa

©Zen Sekizawa

TRENDING

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

‘YUGEN’ at Art Fair Tokyo: Illumination through Obscurity

In this exhibition curated by Tara Londi, eight international artists gave their rendition of the fundamental Japanese aesthetic concept.