‘Butoh’, the Revolutionary Dance of Shadows

Having emerged in a post-war period marked by protest movements, this subversive art rejects traditional artistic conventions.

© Courtesy of Keio University Art Center / Butoh Laboratory, Japan

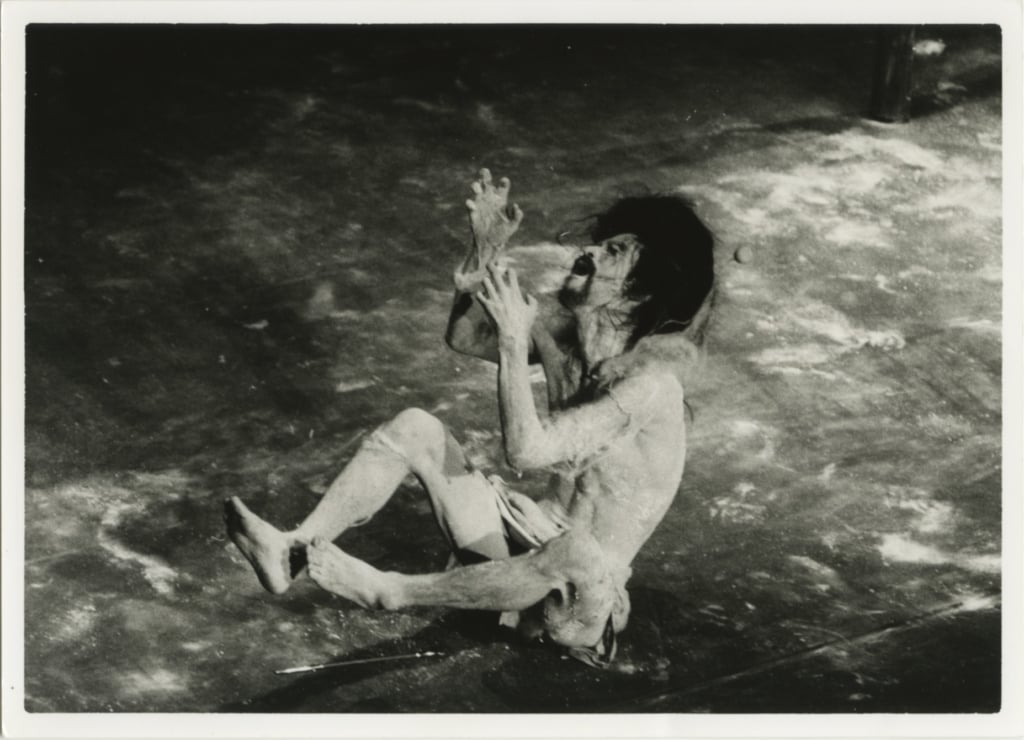

Ankoku Butoh means ‘dance of darkness’ but also ‘compulsive movements in the dark’. It emerged in the 1960s thanks to pioneer Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986).

Inspired by European artistic movements including expressionism (a 20th-century art movement) and surrealism (a 20th-century literary movement), this avant-garde form of dance aimed to heal the traumatic wounds left by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It also portrays the protests by students and artists against the American military presence on Japanese soil.

Bodily release

Impregnated by Buddhism and shinto beliefs, butoh dance challenges aesthetic concepts through non-conformism. On a minimalist stage, dancers with shaved heads move their bodies (considered as a living work of art), whitened with rice powder and virtually naked. To express strong emotions like pain and terror, the movements are disjointed and slow, but also grotesque. The facial expressions are contorted.

Provocative, violent, transgressive… This poetic spectacle, born out of the distress of a broken country, proves to be a foreshadowing of death due to the artists’ ghostly appearance. ‘On these mountains where no grass grows, searching for my thoughts in all the suffering, I myself become a ghost’, wrote the second founder of this art, Kazuo Ohno, in the accompanying notes for his work The Dead Sea (1985).

Kinjiki or ‘Forbidden Colours’

In 1959, Tatsumi Hijikata shocked the public with the first stage performance of this subversive dance. Adapting the novel Kinjiki (‘Forbidden Colours’), written by Yukio Mishima in 1953, he addressed a subject that was still prohibited in Japan: homosexuality.

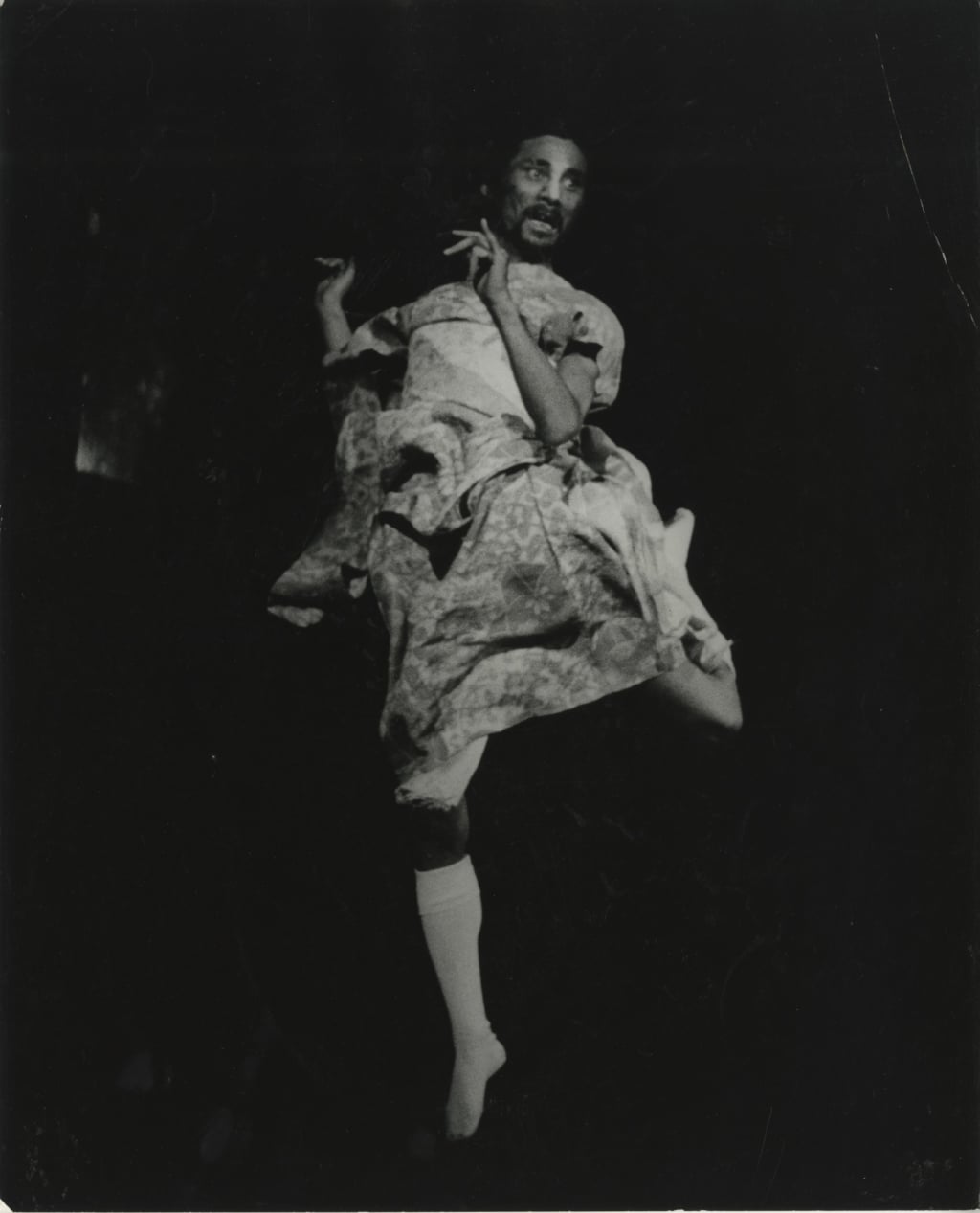

A manifesto against established art, social norms and conventional beauty, the dancers transgress the taboos imposed on the body. Thus, the audience witness a new revolt whereby the main character cross-dresses, sometimes with a metal phallus around his waist or holding a cockerel between his thighs.

Today, the artistic heritage of the pioneers is still very much alive and indeed claimed by a new generation of butoh dancers. The dance retains a quality that is both disturbing and rebellious. The contemporary dance company Sankai Juku (‘studio by the mountain and the sea’), founded in 1975 by Ushio Amagatsu, puts on organic performances that play with shapes and colours.

More information about butoh can be found on the website for the Kyoto Butohkan theatre (now closed) that was dedicated to the art until 2021.

© Courtesy of Keio University Art Center / Butoh Laboratory, Japan

‘KAGEMI-Beyond the Metaphors of Mirrors (recreation)’, © Sankai Juku

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.