Japanese Society and Self-Harm

Photographer Kosuke Okahara followed six young girls experiencing suffering in 'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-'.

“Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-” © Kosuke Okahara

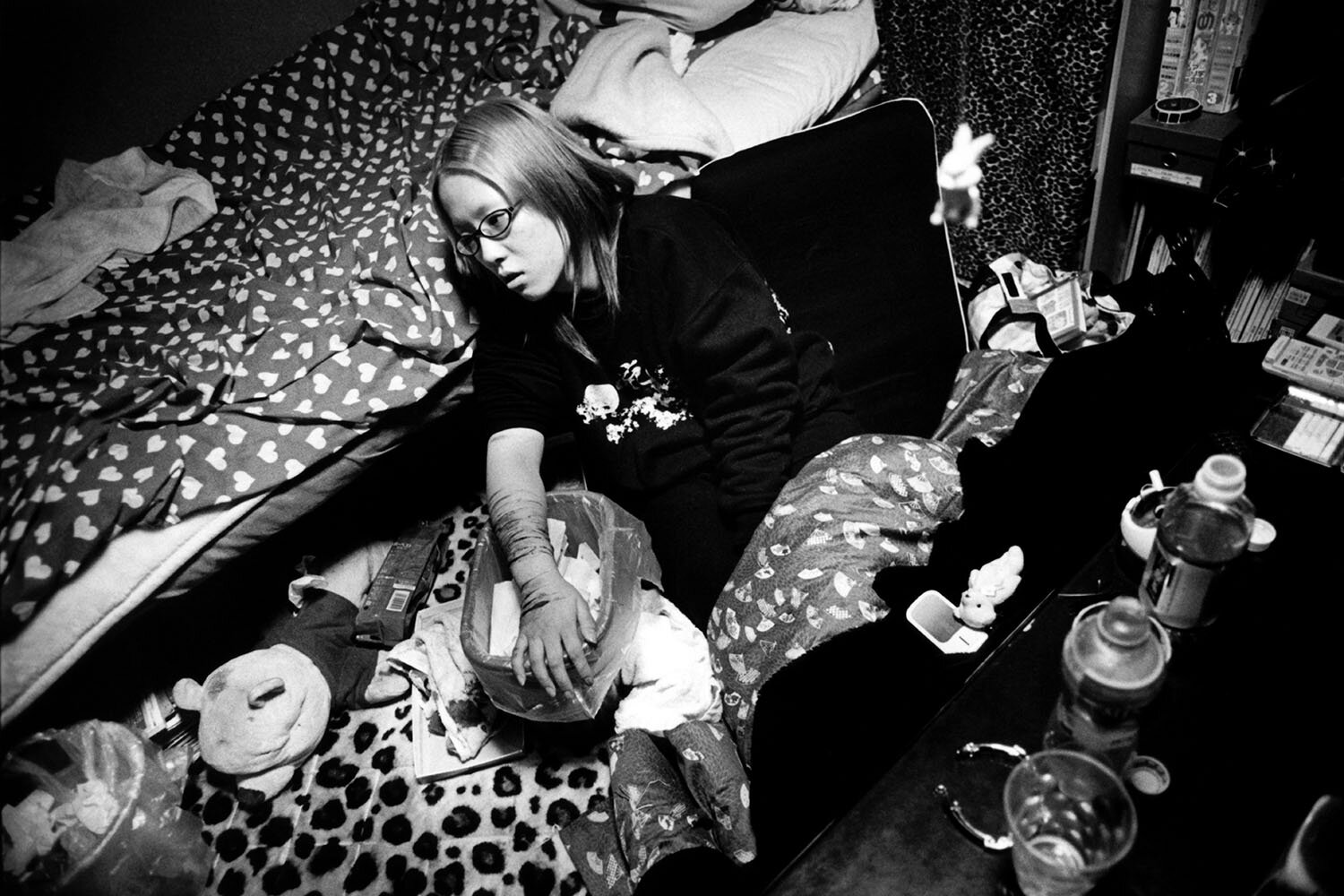

Kosuke Okahara presents the public with a harsh reality, born out of forced migrations and political or social issues. In the series Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-, started in 2004, he examined a phenomenon that Japanese society refuses to acknowledge and address: self-harm among adolescents.

Born in 1980 and a former member of Agence VU’, it was upon hearing a young girl declare Ibasyo ga nai, which translates into English as ‘I don’t fit in’, that Kosuke Okahara decided to undertake this project, which would extend over a period of eight years. Thus, he followed six young girls who self harm. The photographs are divided into six series, and depict situations triggered by various causes, such as poverty, bullying, or domestic and sexual violence.

Emerging from anonymity

The photographs show these young women in ordinary situations in their everyday life. The photographer follows them in dramatic moments, moments of suffering, immortalises the medication ingested and the scars from self-mutilation—actions that could prove fatal.

As curator Thomas Doubliez explains in a text written for the Polka Galerie, which represents the artist, Kosuke Okahara ‘gradually assumes the roles of photographer, close friend, witness, and even first aider. Releasing patients from anonymity, Ibasyo shatters a real taboo in Japanese society and can be considered to exemplify the ethical and aesthetic approach taken in his work.’

Issues that still receive little attention

In a society that aims to be harmonious and that does not take responsibility for its flaws, or at least does not wish to acknowledge them, Kosuke Okahara raises the broader question of Japanese identity with this testimony. As he explains to Pen, ‘the issue of mental health is easier to address now in Japanese society; sick leave is offered in cases of depression, for example, but self-harm and violence still receive little attention.’

The photographer’s perspective is marked with empathy, but never pity; this position is also demonstrated in another of his projects, Vanishing Existence, in which he examined the situation of a leprosy village in China.

Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence- (2018), a series of photographs by Kosuke Okahara, is published by Kousakusha.

'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-' © Kosuke Okahara

'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-' © Kosuke Okahara

'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-' © Kosuke Okahara

'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-' © Kosuke Okahara

'Ibasyo -Self-injury, proof of existence-' © Kosuke Okahara

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

Paris, Tokyo: Robert Compagnon

With his co-chef and talented wife, Jessica Yang, Robert Compagnon opened one of the top new restaurants in Paris: Le Rigmarole.

3:31

3:31 -

Chiharu Shiota, Red Threads of the Soul

Last year, more than 660,000 people visited the retrospective 'Chiharu Shiota: The Soul Trembles' exhibit at the Mori Art Museum.

-

‘Before Doubting Others, Doubt Yourself. Who Can Truly Say a Dish Isn’t What It Used to Be?’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.

-

The Story of Sada Yacco, the Geisha who Bewitched Europe

Described by Dazed magazine as the first beauty influencer, she has been restored to her former glory since 2019.