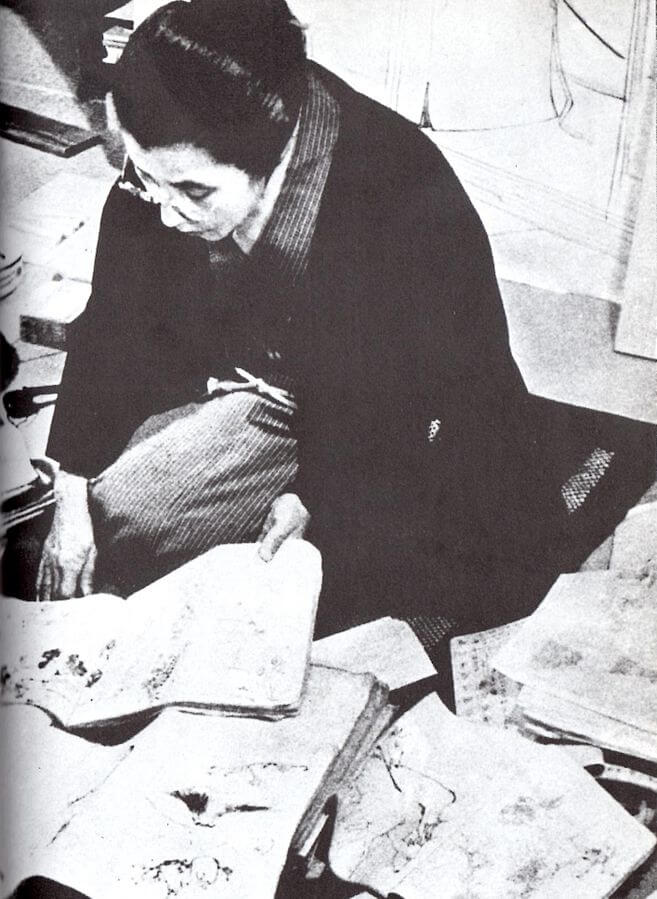

Shoen Uemura, a Woman Armed with a Paintbrush at the Turn of the Century

As the Edo period was nearing an end, the conventions restricting female artists persisted. Shoen Uemura fought to open doors.

© Uemura Shoen ‘Firefly’, 1913 and ‘Mother and Child’, 1934 - Wikimedia Commons TDR

A woman of the people who was appointed court painter, Shoen Uemura (1875-1949) spent her life fighting against the conventions that restricted women to practising their talents as artists in the privacy of their own home, without ever receiving any recognition.

From a life of sacrifices and battles, she managed to extract a remarkable talent that could not be ignored in her country and beyond, both in her own time and today.

Fighting to open doors

Born in Kyoto to a family of merchants, the young Tsune Uemura, whose father died when she was very young, grew up surrounded by strong and independent women who supported her in her calling to become a painter. From an early age, she stood out due to her particular gift for art, and was accepted into the painting school in her prefecture. She was taught by artist Shonen Suzuki, having been held back herself in her learning due to the fact women were not allowed to take classes that were reserved for men, and she hailed her talent by giving her her artist’s name, Shoen, taking the first kanji of her own name. Despite being a woman, she stood out among her class, and her first award-winning painting was purchased by none other than the Prince of England, the son of Queen Victoria, in 1890, when she was just fifteen years old.

Despite having now achieved fame, the artist kept her momentum. She received numerous awards, was noticed everywhere she went, and was even chosen by the government to represent her country as part of a group of artists at the Chicago World Exposition in 1893. Slandered and sabotaged by her peers of the opposite sex, Shoen Uemura continued her career, humiliating them in the process due to her success, or when one of her rivals wrecked one of her exhibitions and she left it the way it was. Throughout her life, she remained artistically active and entered the imperial court as its official artist in 1944, making her only the second woman to achieve this feat. By the end of her life, she had received the highest honours, as she was awarded Japan’s Order of Culture and became the first woman to do so one year before she passed away, in 1949.

The artist for all women

A prolific artist, Shoen Uemura specialised in portraits of women, celebrating them not through finery or luxurious decor, but through the finesse of her lines and her ability to enhance their faces, gestures and outfits. Her work was in the Nihonga style (‘Japanese painting’), which she defended passionately against the Western influences that were becoming established in the country.

While each of her paintings has its own interest, history particularly remembers her portraits of women of the people, who were very seldom depicted in her favourite sub-genre, Bijin-ga (‘pictures of beautiful women’). Usually reserved for representations of courtesans, princesses and noblewomen, Shoen Uemura subverted the genre’s conventions, representing the women she held in the highest esteem: mothers raising their children, wives performing exhausting household tasks, fearless young brides, female friends laughing freely, or heroines in Noh theatre performances. For the latter in particular, she was hailed for snubbing tradition by using female models, when the roles in this classic form of theatre were usually played by men. Thus, the painter restores the right amount of femininity that goes back to these inspiring fictional characters.

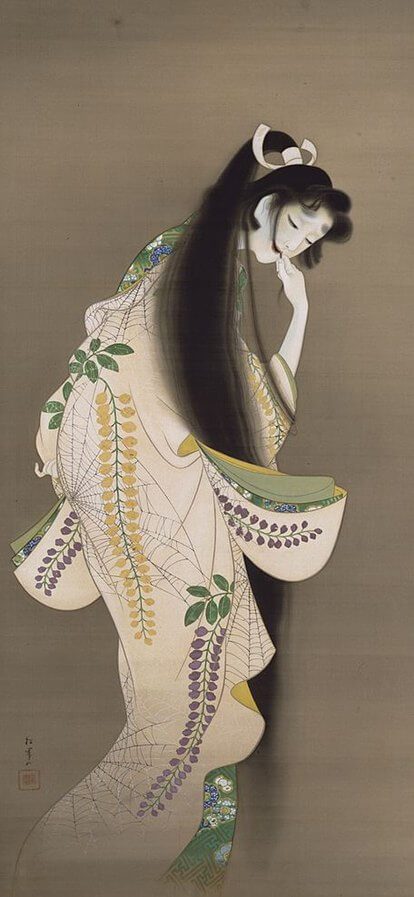

Her strength of character only failed her for four years, during which time she produced virtually nothing, having been emotionally wounded by a breakup. She never married, let rumours spread about a possible liaison with her teacher, and never revealed the identity of the father of her children. However, it was during this dark period that Shoen Uemura produced the most original masterpiece of her career, Flame, which depicts a terrifying woman with the features of a vengeful spirit dressed in a kimono covered in cobwebs…

Shoen Uemura was the painter of ordinary women, heroines from history portrayed in theatre, and merciless, vengeful female demons. She was ahead of her time and opened doors for other female painters, and is still celebrated in her country and indeed internationally: her character and talent continue to pervade memories and museums alike. Indeed, a retrospective was held in her honour at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art in 2021.

Uemura Shoen (2021), an exhibition that took place at Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art from 17 July until 12 September 2021.

© Uemura Shoen - Wikimedia Commons TDR

© Uemura Shoen ‘Flame’, 1918 and ‘Daughter Miyuki’, 1914 - Wikimedia Commons TDR

© Uemura Shoen ‘Large Snowflakes’, 1944 - Wikimedia Commons TDR

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.