Shunga: an Erotic Art First Admired, Then Prohibited

©Wikimedia Commons

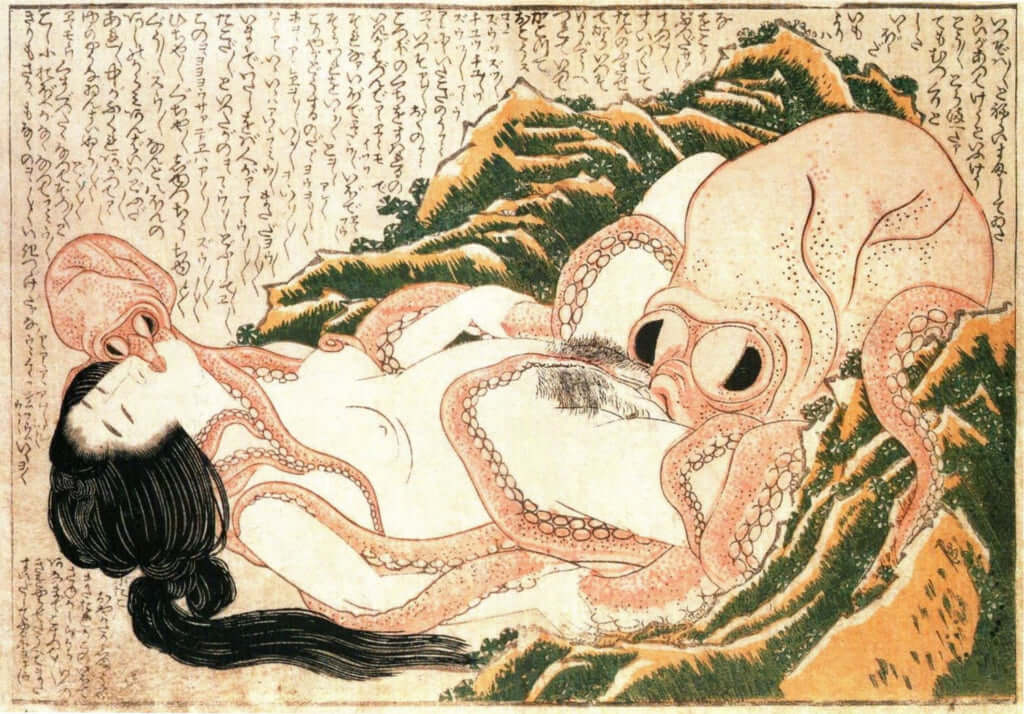

The emblematic master Hokusai is still linked with engravings where nature is queen, but one of his most celebrated works has a far less pastoral theme. ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’, which dates back to 1814, depicts a woman in the throes of passion with two octopuses. This wood engraving very much forms part of the artistic movement of shunga. The term translates literally to ‘picture of spring’, a euphemism to evoke the sexual act. Shunga is a prolific art which reached its peak during the Edo period (1600-1868) and captures intimate moments in the act. Eminently inventive and marked by a liberated sense of sexuality, whether heterosexual, homosexual or solo, shunga celebrates the world of pleasure with a sense of boldness.

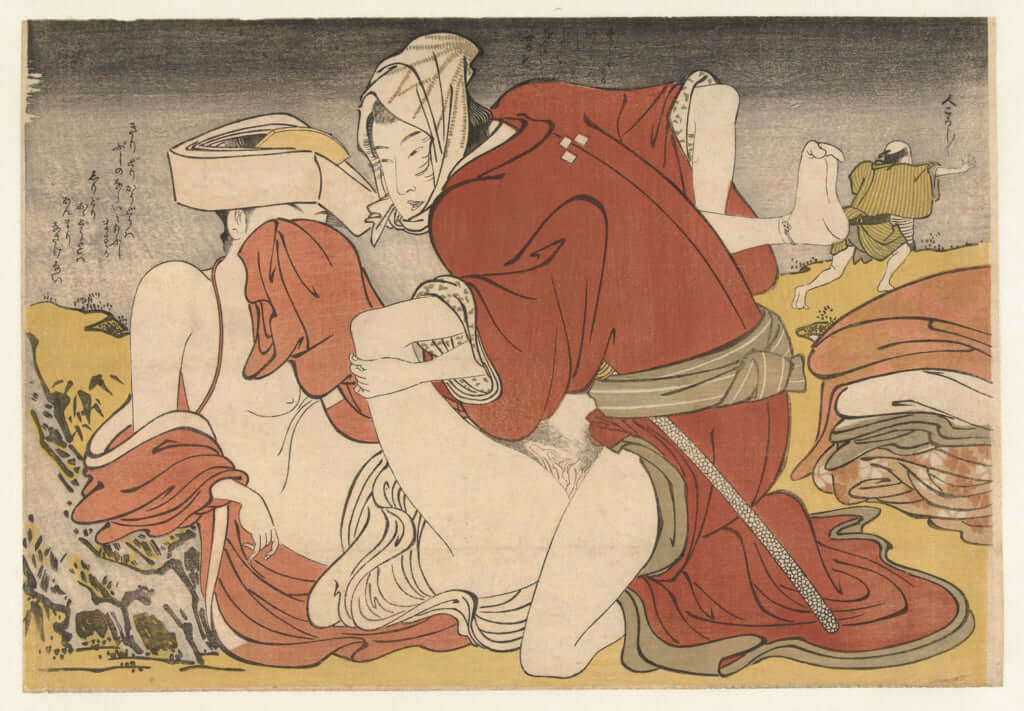

When this erotic art first came into being, the engravings were only available to the higher echelons of society. However, as their production and distribution intensified, they won over a wider audience. Considered as talismans for merchants and warriors who kept them carefully tucked into the sleeves of their kimono, or offered as a wedding gift as an instruction manual for the wedding night, shunga prints sought to normalise sex, despite the coldness of Confucianism with regard to the content which challenged Puritanism. In contrast, Shinto has always seen sex as ordinary, providing that it is not abused. According to Shinto mythology, the first Japanese island, Onogoro, was created by a symbolic ejaculation from the god Izanagi, while all the other islands emerged from the womb of his wife, the goddess Izanami.

©Wellcome Trust

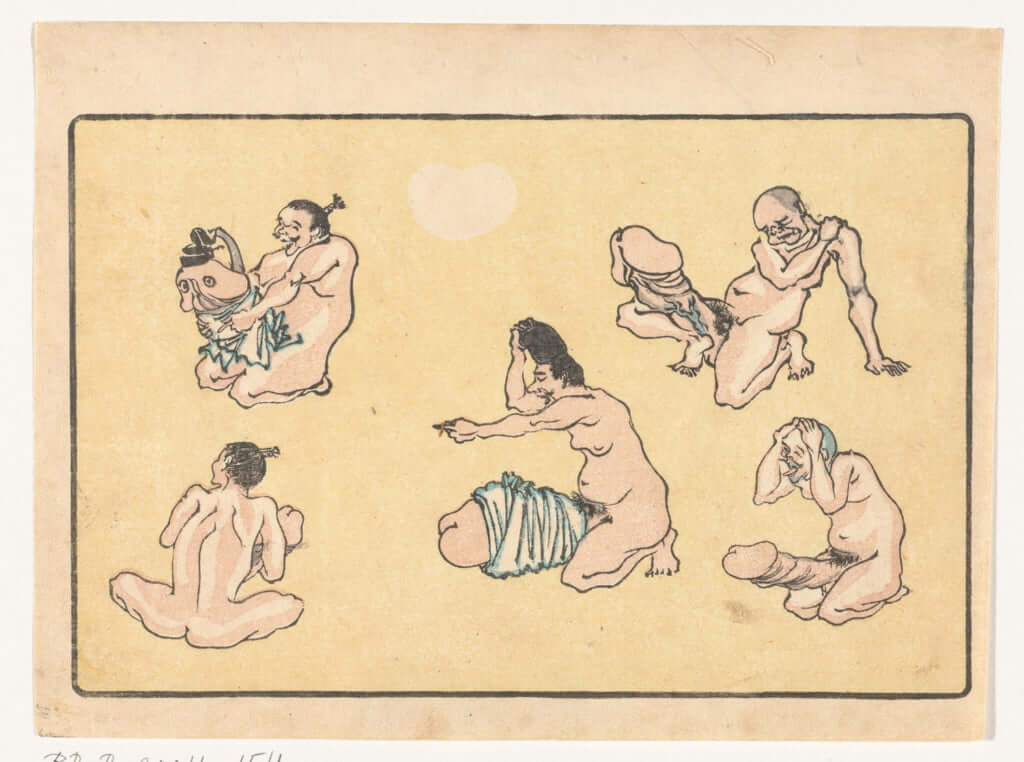

Neither taboo nor shameful, shunga prints are appreciated for their sexual nature but also contain humour, like the engraving depicting a cat playing with its owner’s genitals while the latter is maxing love to a woman. The majority of the protagonists in the scenes are dressed and indeed can be recognised by their costumes, which allow the viewer to place them on the social scale and instantly understand whether the lovers are a courtesan and a kabuki actor, for example. In any case, clothing is not a device to conserve modesty; instead, it actually serves to attract the attention to certain parts of the body. Often, the artists wish to accentuate the eroticism of their art by exaggerating the size of their subject’s sexual organs, in the same way as in the erotic Chinese paintings from the Muromachi period (1336-1573) which depicted exceptionally large genitals.

The art of shunga was censored in 1722. However, the engravings continued to be produced and sold in secret until the start of the 1900s. After the Meiji Restoration (1868) and the introduction of photography, the era of shunga drew to a close. Despite this, it continues to inspire anime and manga pornography, which has now become a genre in its own right, named ‘hentai’. The freedom of expression of these erotic Japanese engravings has also provided an endless source of inspiration for western painters such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas and Picasso. More recently, an exhibition at the British Museum in London held in 2013 and at the Eisei Bunko Museum in Tokyo in 2015 enjoyed great success, despite a few complaints aimed at some works which were deemed obscene. This frigidity in the face of erotic art cannot, however, eradicate the abundant fertility of shunga. Respected for its sexual and humorous character, it has formed, in the eyes of many, one of the pillars of ukiyo-e, the notable artistic movement of the era which favours popular, accessible paintings.

©Rijksmuseum

©Rijksmuseum

©Wikimedia Commons

©Wikimedia Commons

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.