‘BGM’ – Elevator Music in Japan

Beyond the current revival of Japanese ambient music, a deep history of untitled songs plays in the background.

‘Here too, is BGM.....’ Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

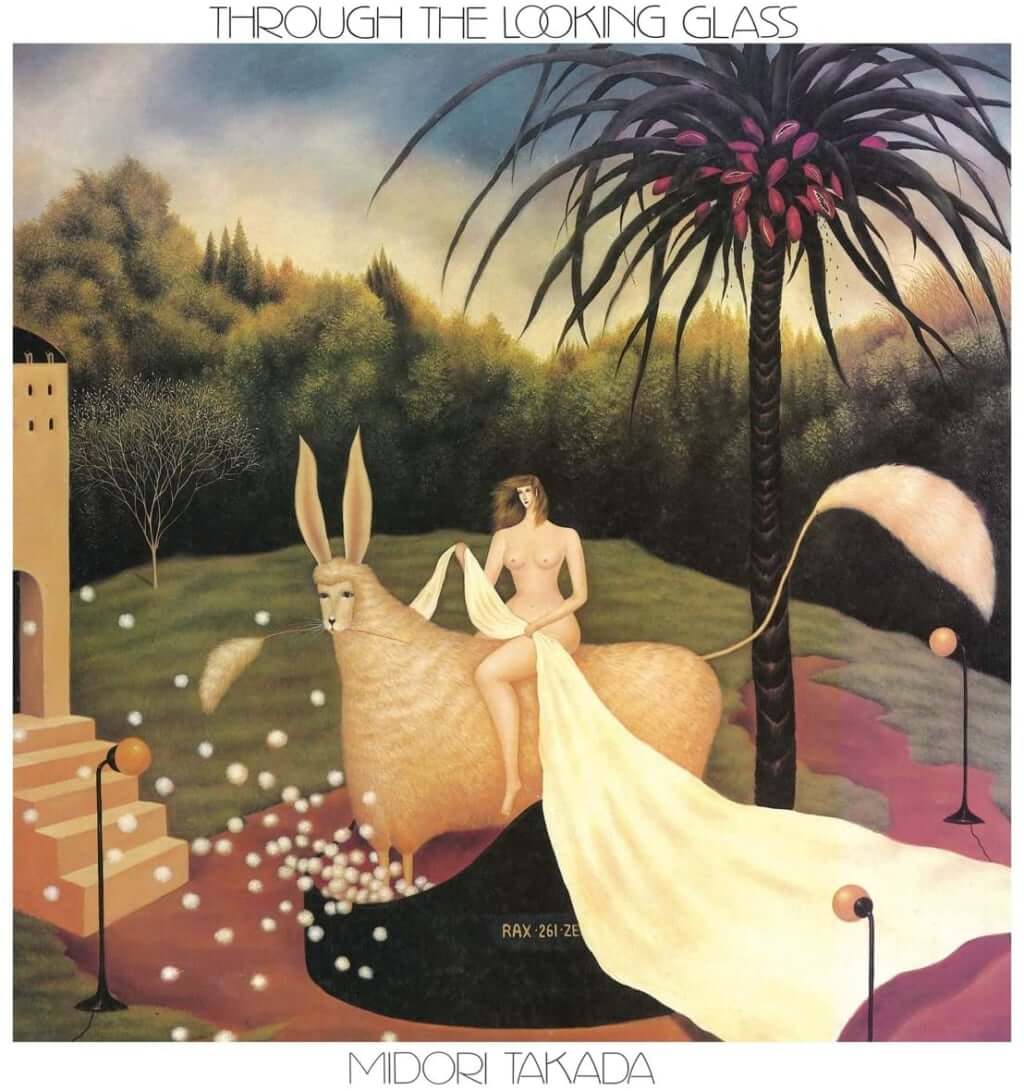

The online revival of Japanese ambient music in recent years has signalled our collective turn towards music’s healing powers. The usefulness of ambience has been widely examined since the early 20th century, and today the breath-taking masterpieces of artists Satoshi Ashikawa or Midori Takada have come to be widely appreciated. But in Japanese modernity, background music—or, termed by Haruomi Hosono, ‘BGM’—enjoyed a distinct relevance.

Under the radical changes of Japan’s post-war environment, diverse experimentation on the potentials of ‘music as furniture’ came together in a single stream. In years of economic growth, elevator music flowed through brand new offices, supermarkets, and shopping streets to discretely convey the mood of a transformed nation as if on the breeze of an air-conditioning unit.

The Floating Catalogue

According to Yuji Tanaka’s Elevator Music in Japan, BGM was a shapeless mid-century modernism that disguised itself in its surroundings, fresh air created by unforeseen technological opportunities enhanced by prosperity and cultural funding.

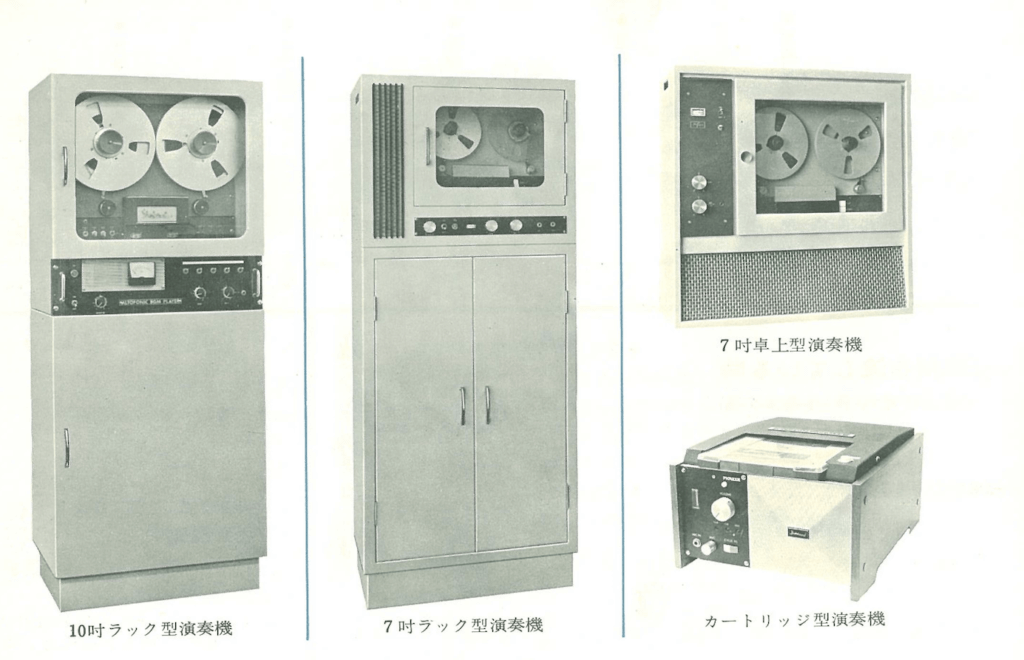

Its first manifestations were looping tonalities of jazz, bossa-nova, and lounge. In 1957, the first BGM studio was built in a room of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel using heavy equipment to broadcast enormous reels of stock music by foreign distributors. The Muzak corporation, an established American supplier, had previously proved that easy-listening increases the productive capacities of the industrial worker. To intrigue Japanese executives further, it cast a trance over the experience of shopping.

By the 1980s, with Japanese audio engineers developing smaller equipment, the revolution had found its common place in urban society. BGM became a transient service with a ubiquitous effect heard in offices, hotels, bowling alleys, and even on fishing boats. At Osaka Expo 74, where Fluxus affiliates showcased state-of-the-art compositions, a league of major BGM corporations provided speakers across its venue to feature ‘environmental music.’

The Future is Formless

Where ethereality was a new focus, futurist connotations flourished under the musicians who were commissioned for the many purposes to make BGM. Haruomi Hosono, who titled the Yellow Magic Orchestra album BGM (1981), originally created ‘Watering a Flower’ for MUJI’s in-store soundtrack. Avant-garde electronic compositions of Isao Tomita appeared in school dance textbooks, and Ryuichi Sakamoto made an experimental CD for pacifying babies distributed in maternity magazines.

BGM became an anonymous art-form, of guiding listeners through modern life by matching music to setting. While flickering between art and banality, its history describes the seriousness of a genre that deliberately fades into the background. Having done so, the current Japanese ambient revival softly tells its story, inviting listeners into entrancing realms once again.

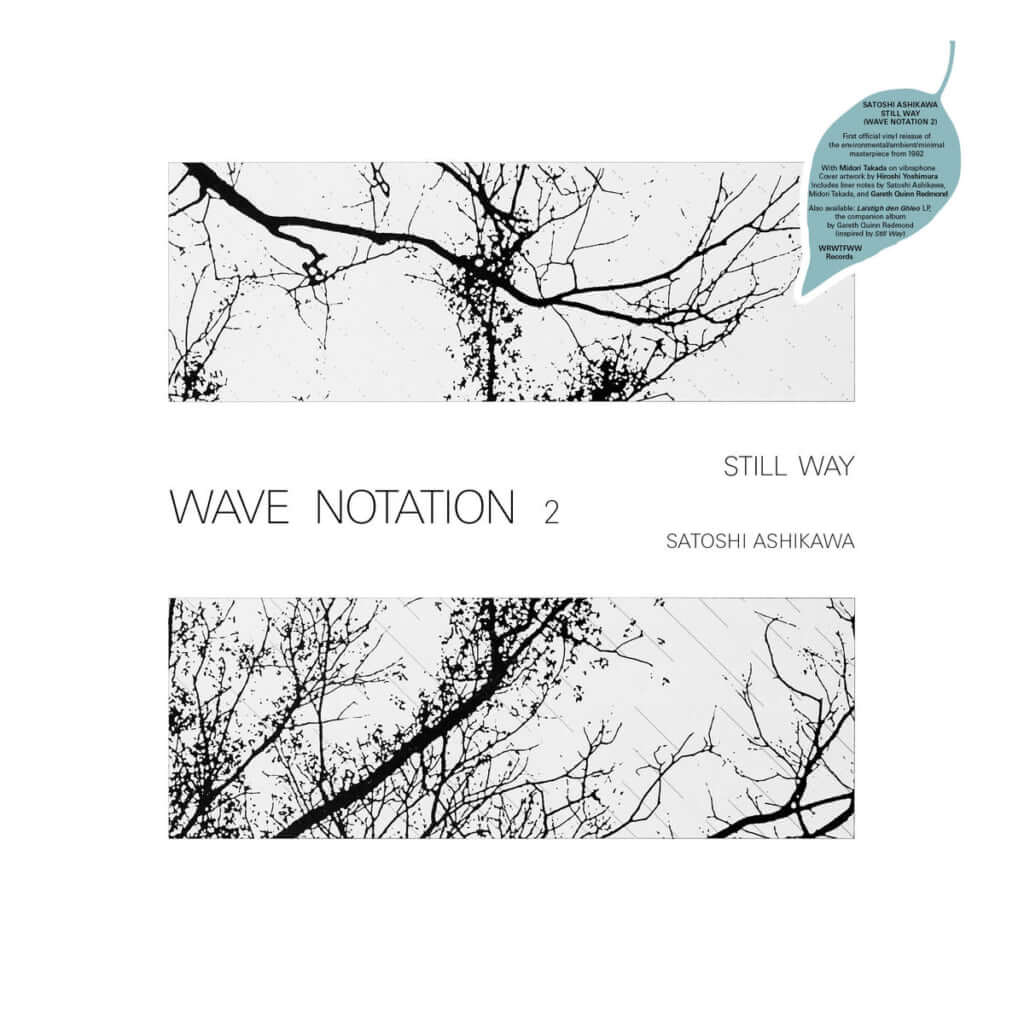

Many lost works of Japanese ambient music are being rediscovered and are increasingly available online. Classics by musicians such as Satoshi Ashikawa or Midori Takada have been re-issued by WRWTFWW Records.

Original ‘BGM players’, beginning as large machines for open reel tapes in the 1950s, then developing into lighter cartridge players by the 1980s. Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

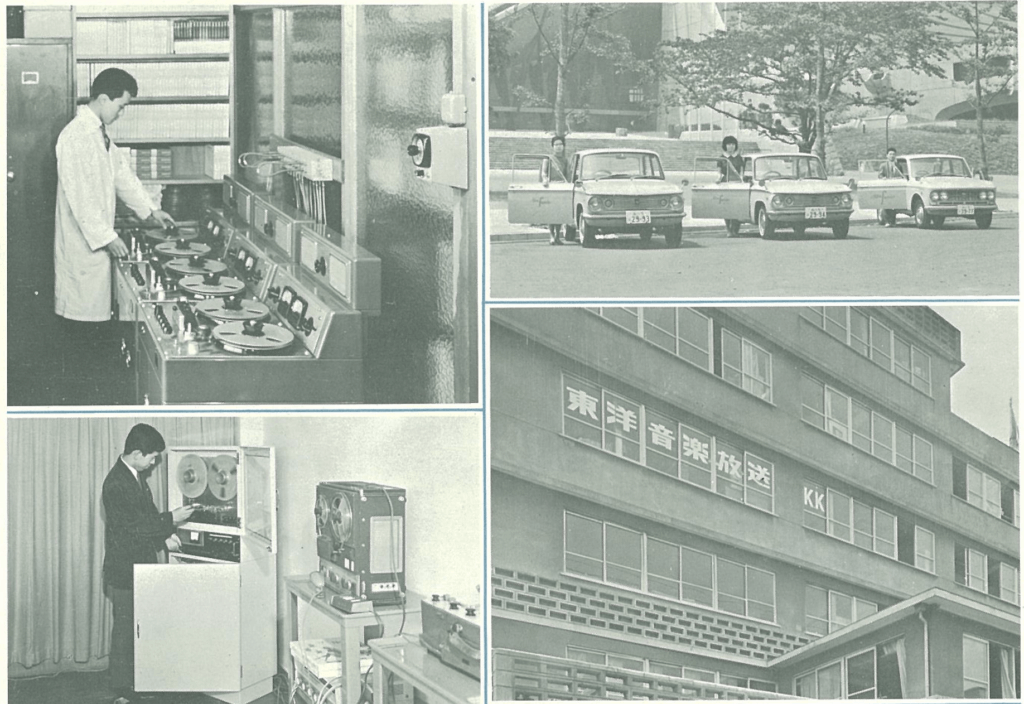

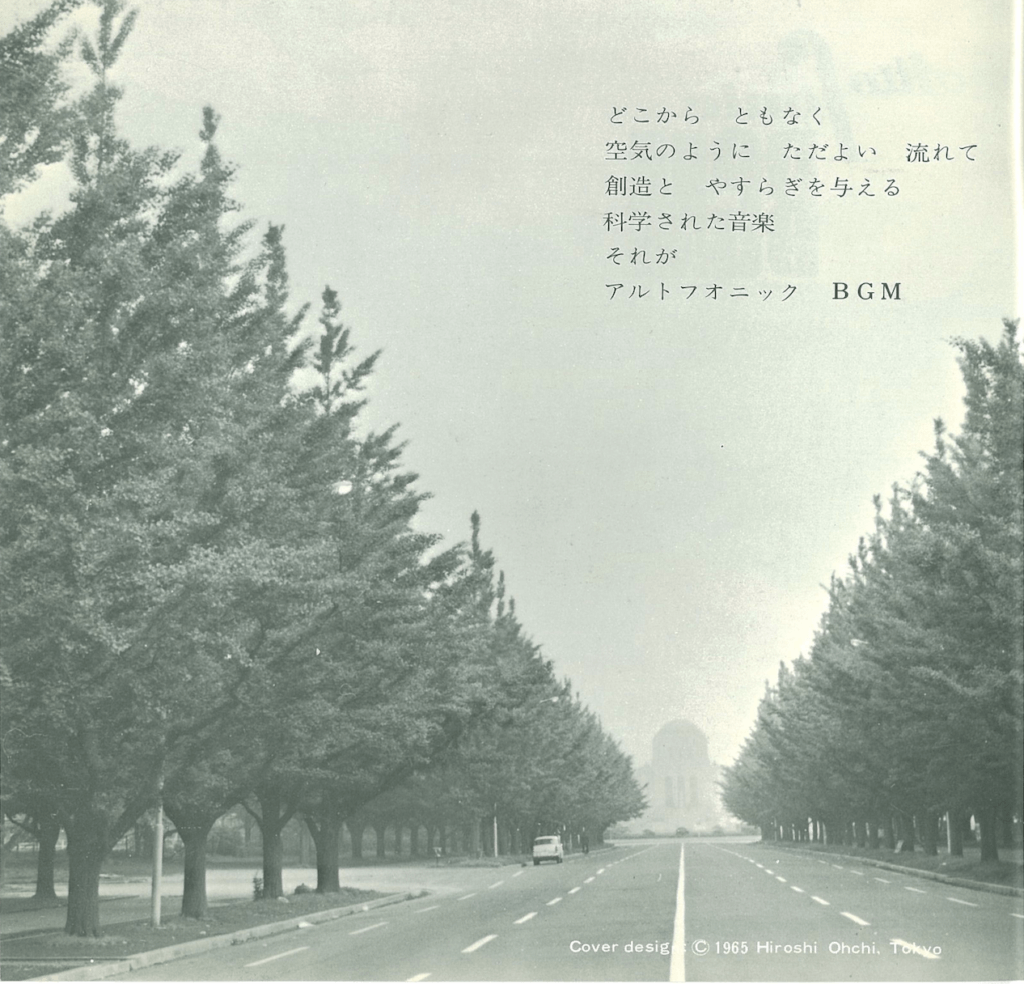

An original record of BGM with the music of the ‘Toyo Ongaku Hoso’ company (1965). Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

The programme rooms of the Toyo Ongaku Hoso company. Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

‘Out of nowhere, floating like the air. Giving creativity and comfort. Scientific music - that is Altofonic's BGM.’ Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

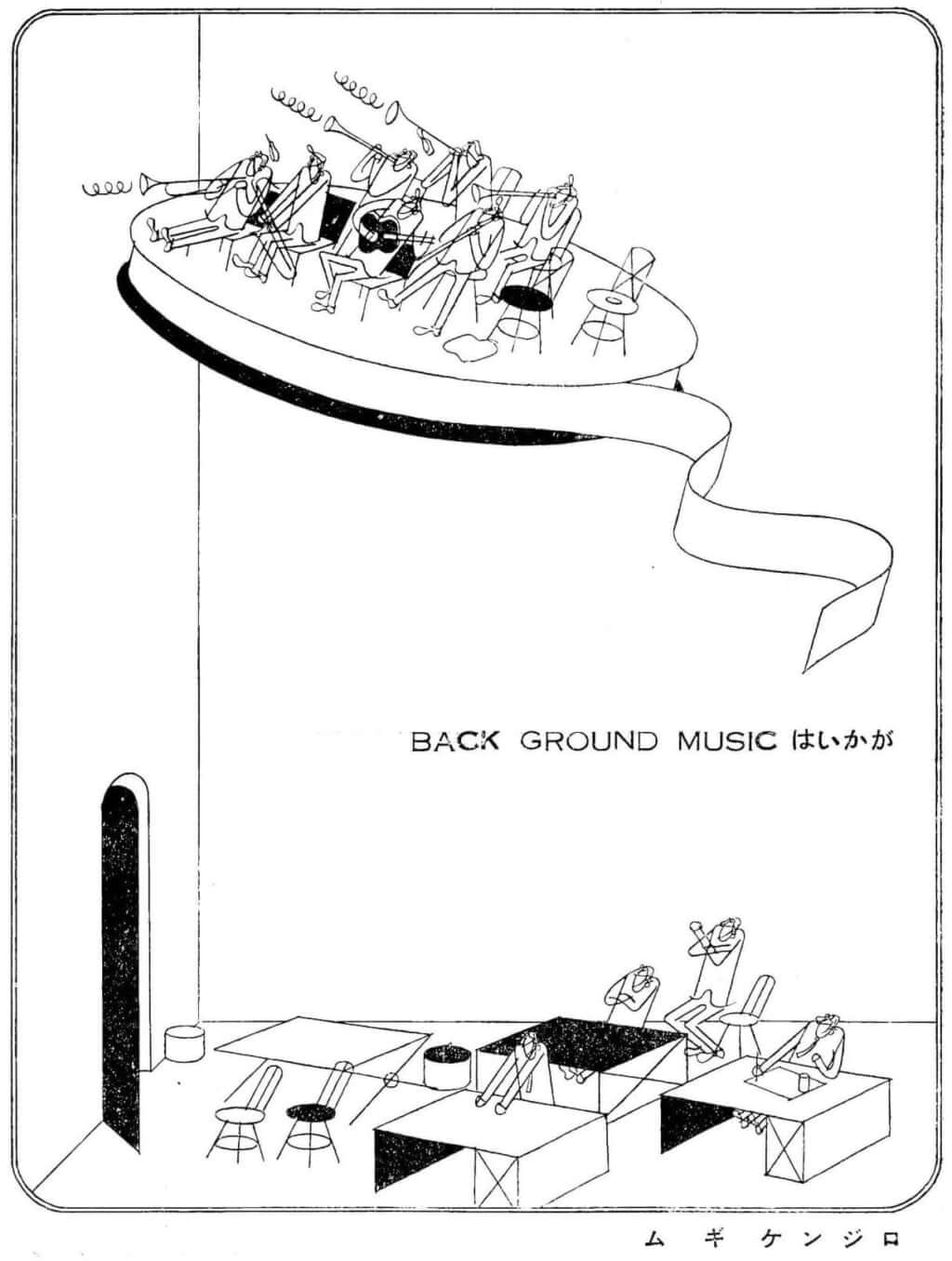

‘Would you like some background music?’ An image from ‘BGM Digest’ (1962). Courtesy of Toyo Media Links.

Satoshi Ashikawa's ‘Still Way (Wave Notation 2)’ (1983). He is considered one of the earliest flag bearers of ambient music in Japan. Courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

Midori Takada's ‘Through the Looking Glass’ (1999). Since her late revival, she has been described as another pioneer of ambient music, channeling African drumming and Indonesian gamelan into her minimalist composition. Courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

Yasuaki Shimizu's ‘Kakashi’ (1982). Yasuaki Shimizu advanced Japan's distinct jazz by fusing it with ambient and new age sounds. Courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

TRENDING

-

A Rare Japanese Garden Hidden Within Honen-in Temple in Kyoto

Visible only twice a year, ‘Empty River’, designed by landscape architect Marc Peter Keane, evokes the carbon cycle.

-

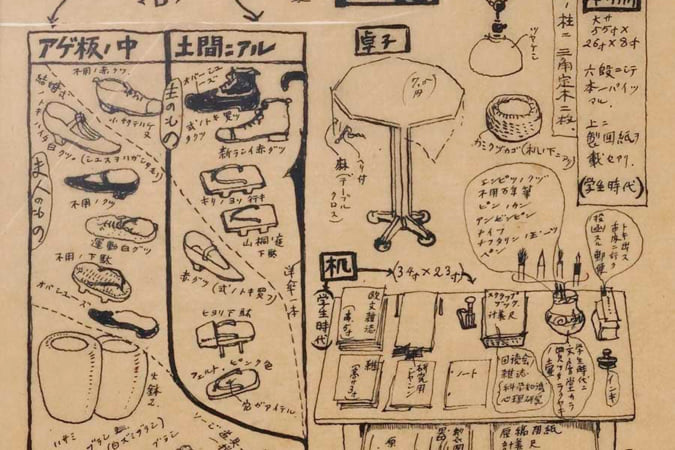

Modernology, Kon Wajiro's Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, organisation of cupboards and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

-

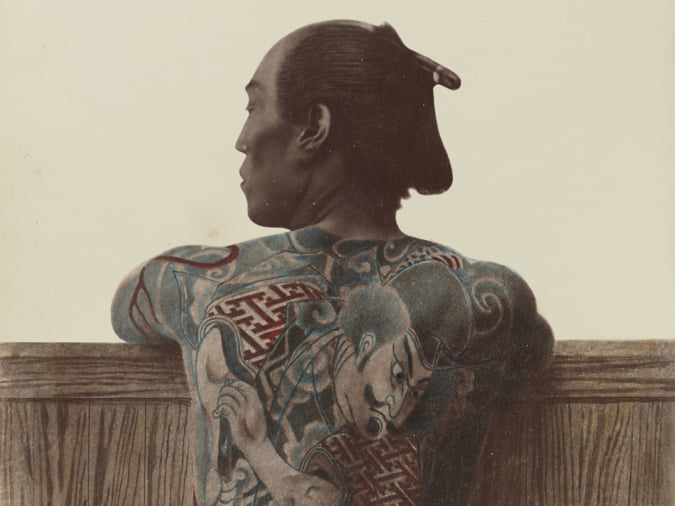

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Hitachi Park Offers a Colourful, Floral Breath of Air All Year Round

Only two hours from Tokyo, this park with thousands of flowers is worth visiting several times a year to appreciate all its different types.