Satoshi Ashikawa, The First Echoes of ‘Kankyo Ongaku’

An essential precursor, ‘Still Way (Wave Notation 2)’ is the only available recording by Japan’s first front runner for ambient music.

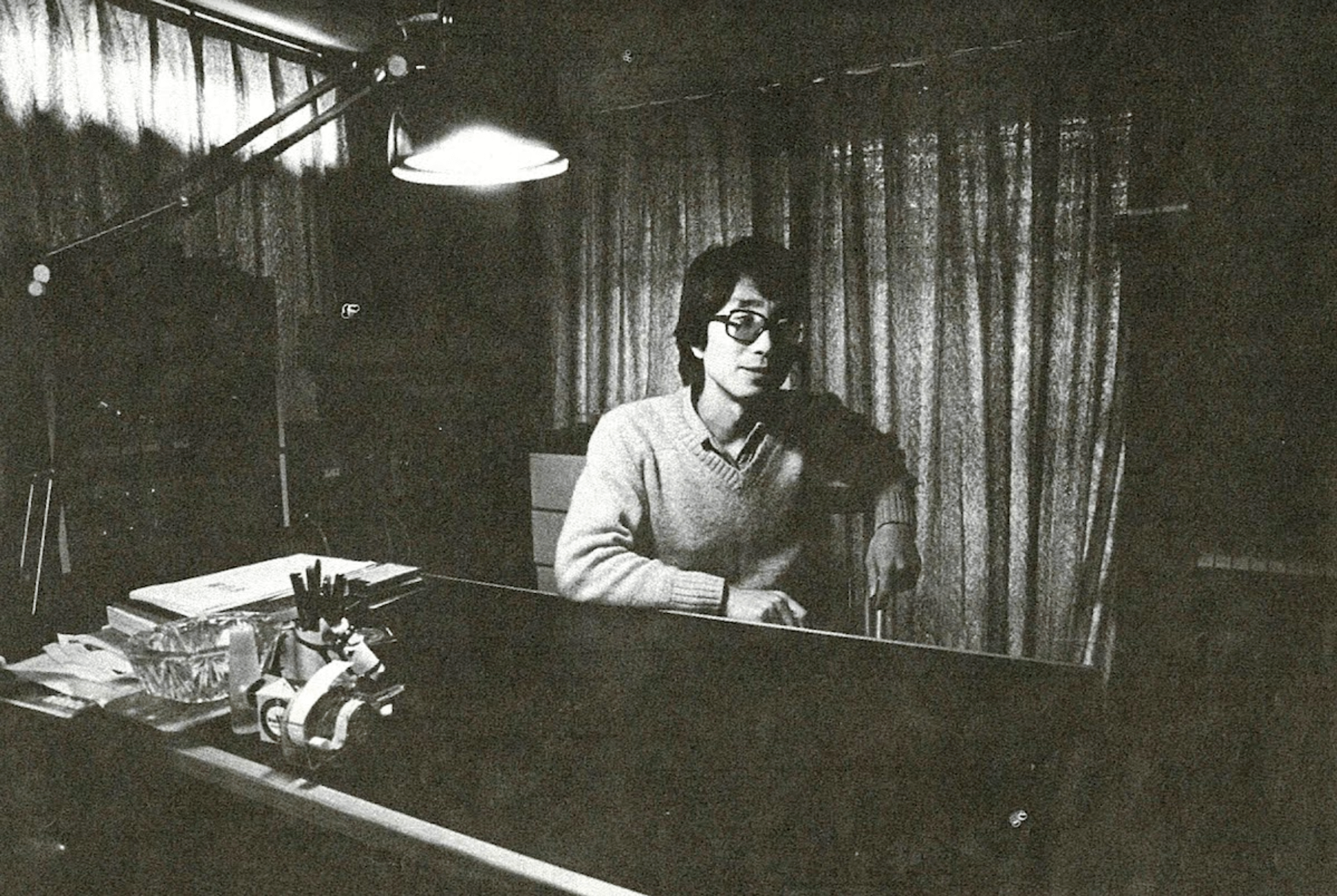

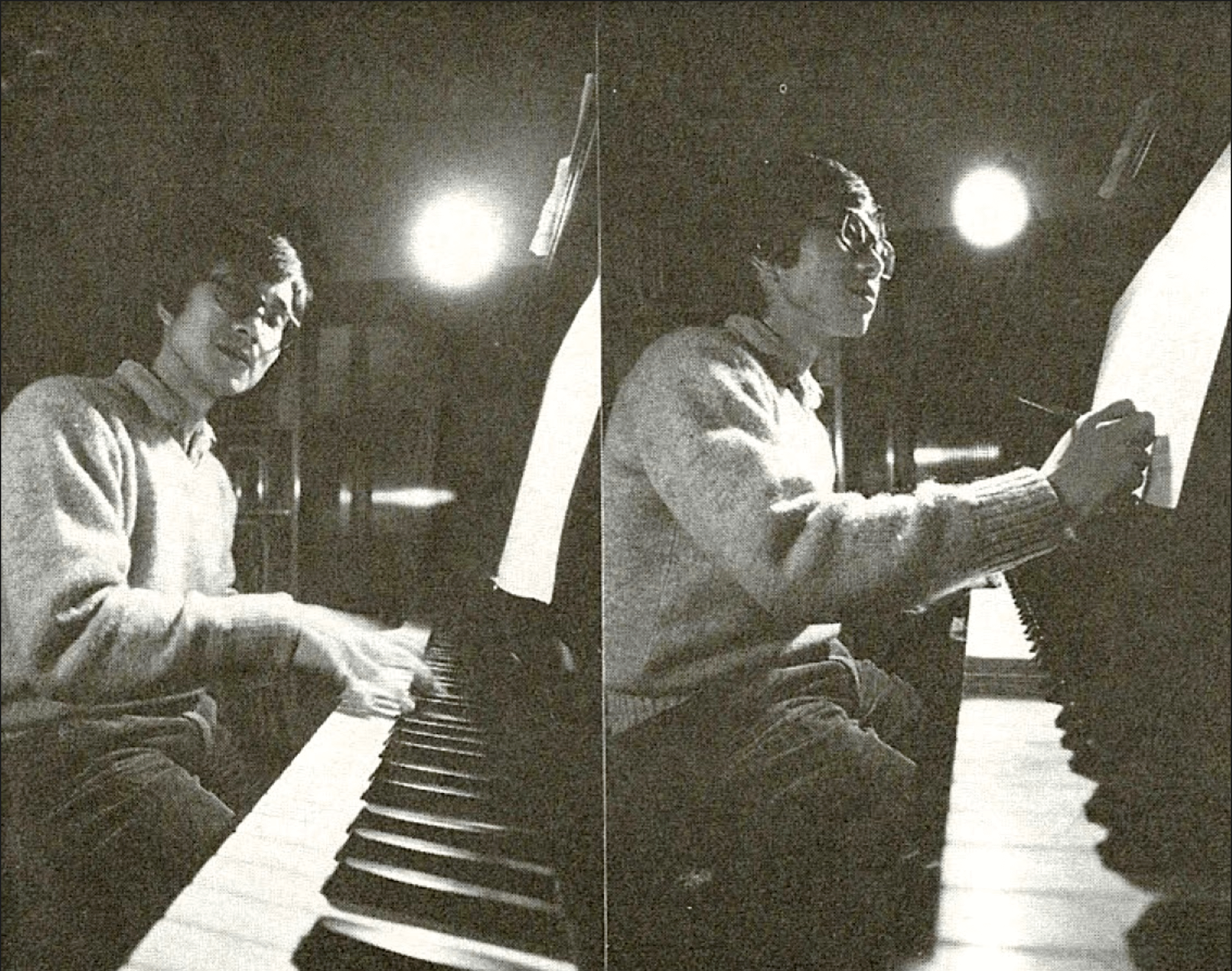

Satoshi Ashikawa, courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

As Still Way (Wave Notation 2) (1982) resounds its notes, all is gently washed away. Subtle and disarming, its tonalities of piano, harp and vibraphone softly grows deeper as it gently invites our attention, making soft ripples before fading back into silence.

Amidst the revival of Japanese ambient music, the first and only record by its earliest flag-bearer Satoshi Ashikawa —minimalist composer, musician and record store owner— continues to reverberate to newer generations. The popularity of his reissues by Swiss label WRWTFWW testifyies to the inherent timelessness of his work.

The Design of Silence

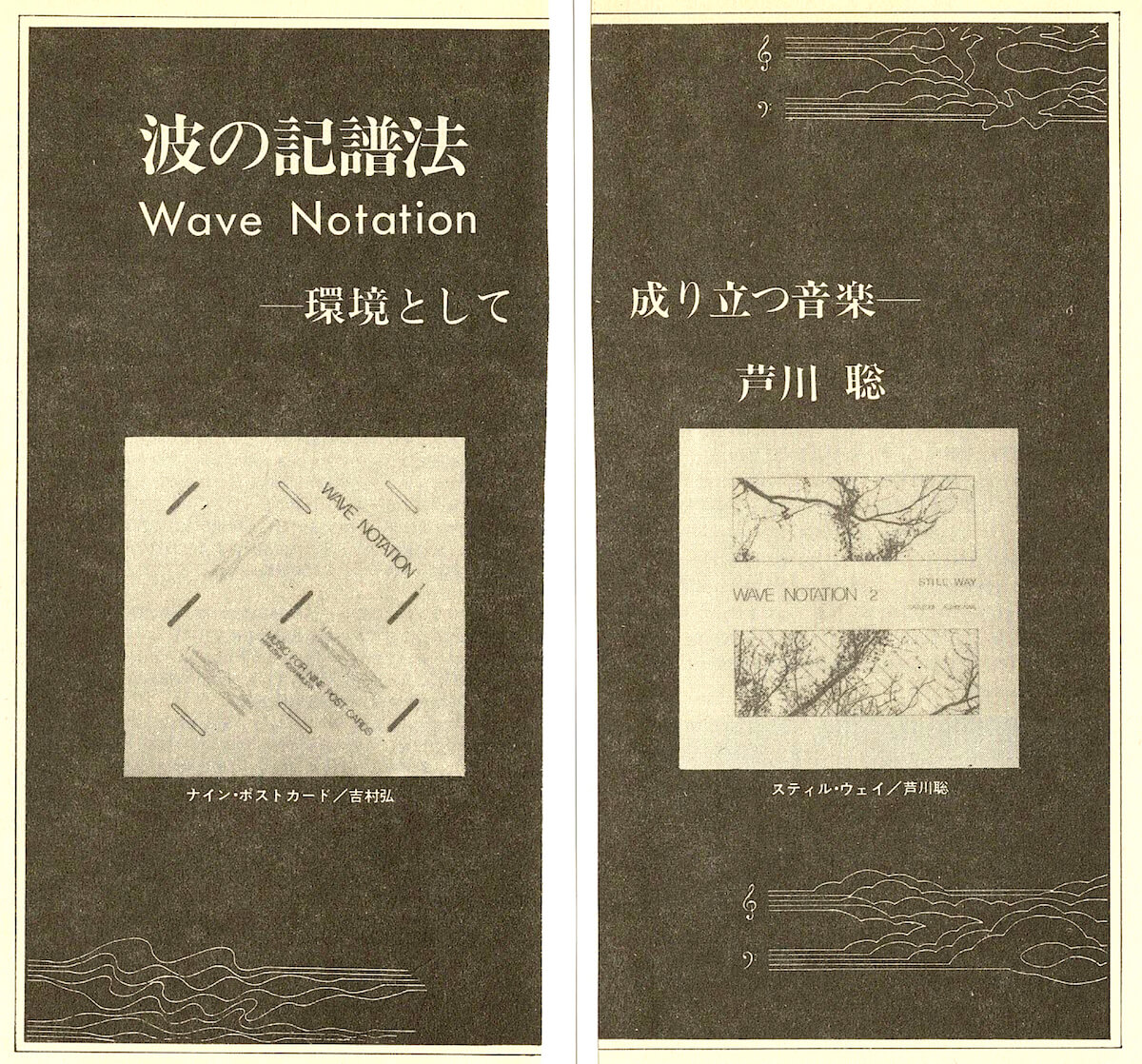

Under Satoshi Ashikawa’s own label Sound Process, Still Way was released as part of his ‘Wave Notation’ series, alongside Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music For Nine Post Cards and Satsuki Shibano’s interpretations of Erik Satie. Demonstrating his philosophy on minimal sound design, Still Way exemplified the advancing of kankyo ongaku (or ‘environmental music’) —an umbrella term of spacious music that, as explained in Satoshi Ashikawa’s own liner notes, ‘would drift like smoke and become part of the environment’.

Kankyo ongaku reflected a new curiosity towards the previous experiments of Western composers —Erik Satie, John Cage and Brian Eno— who were radical in considering more passive modes of listening to discover a genre that focused on atmosphere. But the functional treatment of ambience, or ‘music as furniture’ as put by Brian Eno, resonated uniquely in Japan’s cultural specific context. Much like how dripping water has been a feature of garden designs, sonic elements are historically integrated within traditional aesthetics and their aims to capture a temporality in minimal articulations. Meanwhile, the influence of foreign composers had poured in at the same moment when groundbreaking synthesiser technology was being developed in the Japanese 1980s. Enabled by new horizons of sound design, Still Way became one of the genre’s most important works, often mentioned alongside other masterpieces like Midori Takada’s Through The Looking Glass and Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Green.

Being the first in the country to import Brian Eno’s pioneering records alongside other avant-garde releases through his record store Art Vivant, Satoshi Ashikawa was especially crucial as a link between international minimalists and Japan’s own ambient music circles. He however never saw the influence of his own work, having passed away in an accident a year after its issue. The final aim of his music was to draw our ears inwards, so that in a modern world inundated in noise we may hone in on what truly matters.

Still Way (Wave Notation 2) (1982) is available through the WRWTFWW’s official bandcamp page.

Satoshi Ashikawa, courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

Wave Notation Series. Courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

Satoshi Ashikawa, courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.

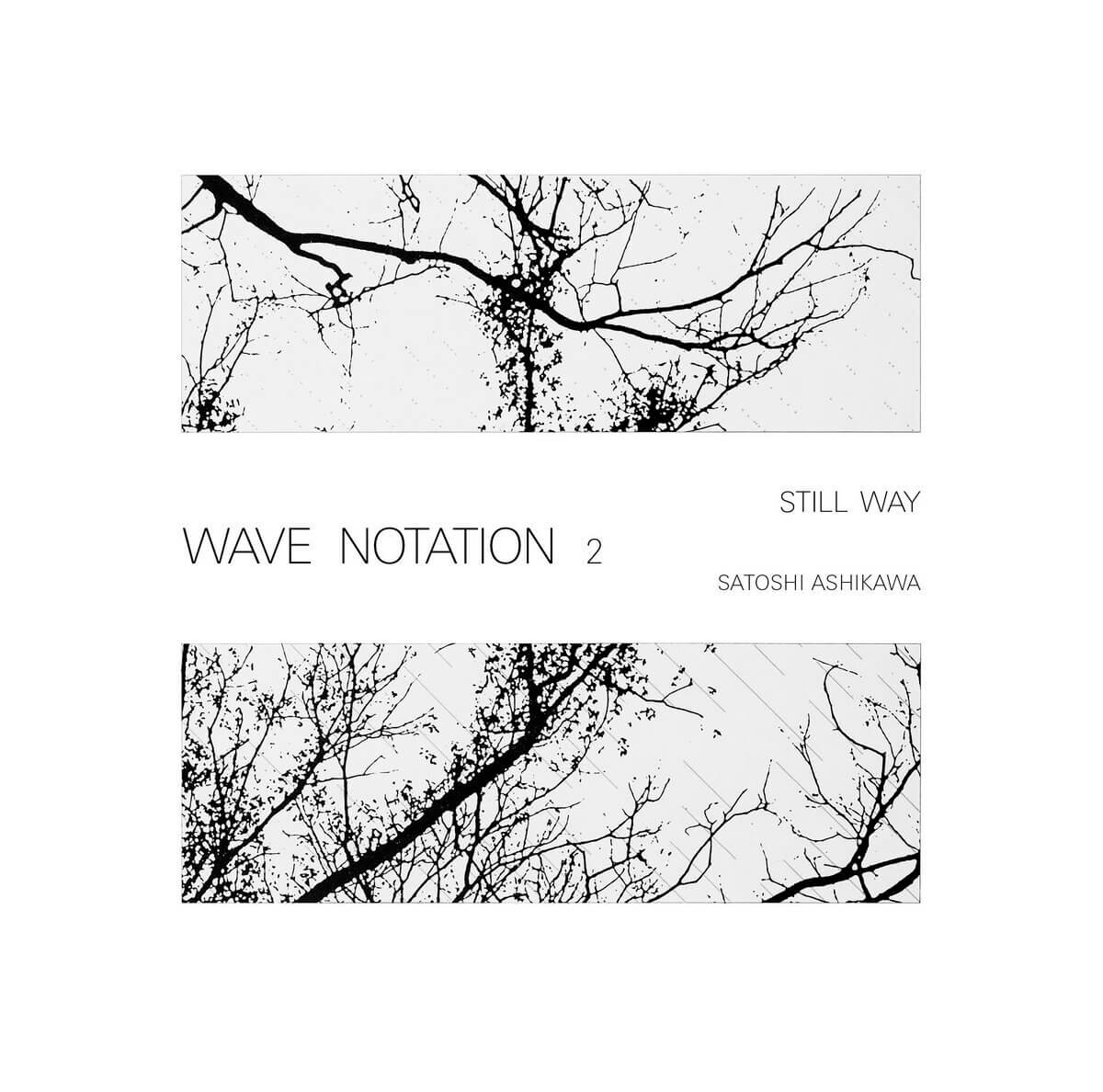

Satoshi Ashikawa ‘Still Way — Wave Notation 2’ (1982), courtesy of WRWTFWW Records.