Shuntaro Tanikawa, the Poet Weaving Words

This globally celebrated author distinguishes himself through his approach to the illustrated book, seen as complementary to poetry.

At nearly 91 years old, Shuntaro Tanikawa continues his daily creative work. Recently, he embarked on a series of nude drawings inspired by the poem ‘Because We Are Naked’ 「ハダカだから」. His poetry seamlessly blends kanji, hiragana, katakana, and the Western alphabet with remarkable freshness.

In Search of the Sensation of the Cosmos, an Interview with Shuntaro Tanikawa, the Poet Weaving Words

For over half a century, Shuntaro Tanikawa has carefully crafted words. As one delves into the monumental collection of illustrated books he has consistently produced alongside his poetry, it feels like a journey back to the moment when language first emerged in the world.

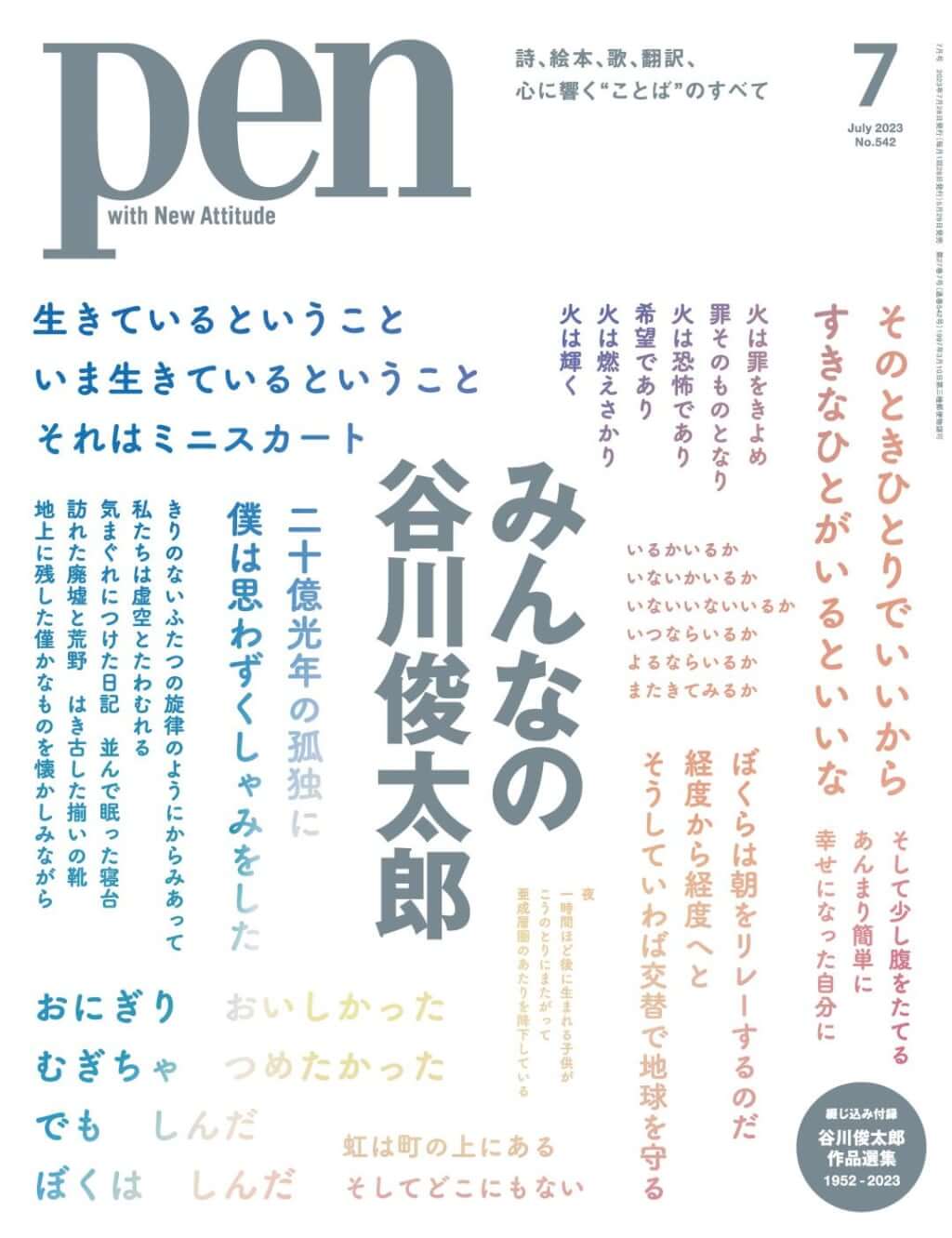

We had the privilege of sitting down with this poet who has embraced the boundless possibilities offered by language. Excerpts from the July 2023 issue of Pen Magazine.

At nearly 91 years old, Shuntaro Tanikawa continues his daily creative work. Recently, he embarked on a series of nude drawings inspired by the poem ‘Because We Are Naked’ 「ハダカだから」. His poetry seamlessly blends kanji, hiragana, katakana, and the Western alphabet with remarkable freshness.

Shuntaro Tanikawa, a poet born in Tokyo in 1931, published his first collection of poems, Two Billion Light-Years of Solitude, in 1952. Not limited to poetry, he is also renowned for writing illustrated books, screenplays, essays, song lyrics, and translations. Over the course of nearly half a century, he has authored more than a hundred poetry collections and illustrated books, earning numerous awards, including the Yomiuri Prize, the Noma Prize for Children’s Literature, the Tatsuji Miyoshi Prize, and recognition at the Struga Poetry Evenings.

In the spring of 2023, the Shuntaro Tanikawa Picture Book Exhibition was held at the Play!Museum in Tokyo, showcasing the poet’s illustrated works among the vast array of his creations. Simultaneously, his new illustrated book, Here is Home 「ここはおうち」, was released, delicately and magically brought to life by the popular artist junaida.

Reflecting on this initial collaboration, Shuntaro Tanikawa reminisced, ‘When I saw the first detailed proofs, their originality struck me, and the words came to me naturally.’

‘When I write,

I always wonder

if my words are suited to our era.’

It’s been 50 years since he wrote his first illustrated book. Do words come to him first, or are they preceded by images? Shuntaro Tanikawa revisited the various creative processes that lead to the creation of an illustrated book, explaining that he seeks to renew his palette of expressions each time.

The story of Here is Home concludes with the appearance of an elderly man holding a tablet, a familiar object for today’s children. With this scene, the author aimed to represent contemporary thinking.

‘When I compose a narrative, I always ask myself if it resonates with our times. It’s a matter of the era, but what matters most to me is how the present is perceived. This is a major theme in my work. However, it seems to me that today, everyone feels like they are losing. Regardless of the number of innovations that enter the market, the real question remains, ‘Do we truly need all these things?’ In the past, the future was open, so we didn’t think about such matters, but today, the possibilities of the future seem to be narrowing. Therefore, I strongly believe that we should not resign ourselves to losing to our era.’

Where is ‘here’? When is ‘now’? These questions have haunted Shuntaro Tanikawa since childhood. One day, he realized that his existence was just a point in the universe. That’s how his work Two Billion Light-Years of Solitude came to him during adolescence.

‘I have only a faint sense of history and have always preferred things of space. The present moment is connected to the past and the future, but this flow of time is not as regular as the ticking of a clock. ‘Within eternity, the present moment’ has multiple facets for me, and that’s what I have always sought to express in my poems.’

Just 50 years ago, Shuntaro Tanikawa focused on the richness and attractions of the Japanese language. In 1973, Wordplay Poems 「ことばあそびうた」 was published, an illustrated book he proudly considers one of his top three works. Words like 「かっぱかっぱらった」 (‘the kappa stole’) and 「かっぱらっぱかっぱらった」 (‘the kappa stole a trumpet’) are examples of wordplay found within, where the repetition of syllables, forming different words depending on their arrangement, creates witty rhyming tales. By rhythmically combining sentence endings, Shuntaro Tanikawa crafts an arrangement as subtle as craftsmanship, all written simply in hiragana.

‘At the inception of language, there is sound. And hiragana is to the Japanese language what sound is to the origin of language. Writing with phonetic symbols like hiragana gives the impression of going back in time. I believe that at the root of Japanese, there is a certain ‘texture’, and I am delighted to have succeeded in portraying it in this book.’

‘Unlike a poem composed solely of words,

accompanying texts with drawings or photographs

allows the world to expand in one stroke.’

Shuntaro Tanikawa often pondered the meaning of words. He also doubted language, just as he believed that certain things could not be expressed through words alone. Illustrated books, therefore, represented a new opportunity for him. ‘Unlike a poem composed solely of words, accompanying texts with drawings or photos allows the world to expand in one stroke and become more tangible.’

As his interest in sounds deepened, Shuntaro Tanikawa ventured into writing illustrated books about onomatopoeias. One of them tells the story of a chick embarking on an adventure, where chirps 「ぴよぴよ」 come from a world where everything is expressed through sound effects or onomatopoeias like 「わんわん」 (‘woof woof’) or 「ぽたんぽたん」 (‘plop plop’). What is a world where one understands a situation solely through the sound of a word or the tone of an onomatopoeia?

‘Today, written culture is so prevalent that experiencing a world where we communicate solely in onomatopoeias, through something as primal as a chick’s cry, struck me as a fantastic idea. If, in addition to having a word that lets us visualize a sound, we have an image to accompany it, we can then guess the sound of a word. Like a babbling child. Like 「ちょちょち」 ‘bababa.’ You might think these are just fanciful inventions of children, but this is the origin of vocalizing language. What influence can this have on human hearing? 「ベタベタ」 ‘beta beta’ (an onomatopoeia for something sticky) and 「ペタペタ」 ‘peta peta’ (patting) are obviously different. And it’s not the reason that decides it but bodily intuition.”

Even when discussing profound topics, Shuntaro Tanikawa occasionally displays a mischievous smile. ‘Lately, I feel like a child wearing an old man's mask. When you live a long time, you become a child again.’

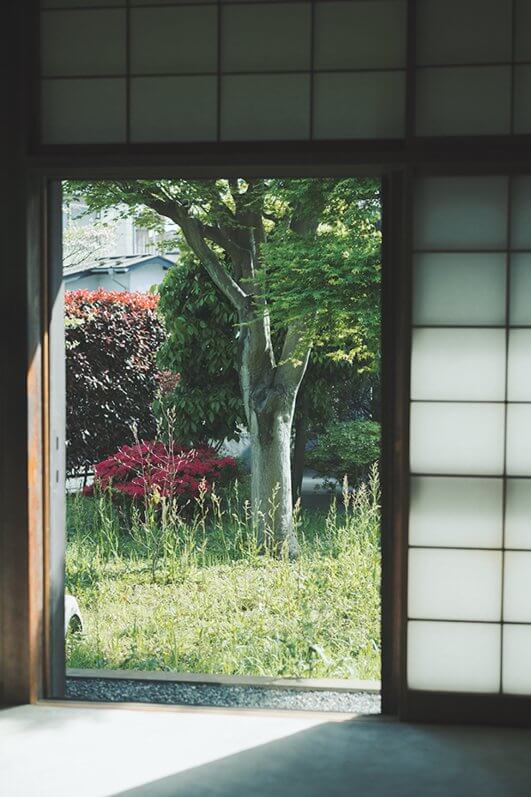

Shuntaro Tanikawa contemplates the changing seasons' effects on the flowers and plants in his garden from his living room. When he was young, he watched the sunrise from this same garden, deeply feeling the morning's beauty, awakening his poet's consciousness.

Originally, not only children but everyone naturally assessed circumstances and sensations through the sound of language. However, with the development of printing and the proliferation of books, written language took a predominant role, and opportunities for oral communication dwindled.

‘Most people care about the meaning of the words they use, but few consider the texture, the tactile-like sensation they can convey. In reality, the same poem, whether in prose or not, can have a different effect on each person. One person may be as sensitive to the texture of words as another may pay no attention to it at all.’

Through illustrated books, Shuntaro Tanikawa believed that not only children but also adults could feel the texture of language. Consequently, he began writing numerous books that made language palpable, starting with the onomatopoeic illustrated book Piyo Piyo 「ぴよぴよ」, followed by the globally renowned work Moko Mokomoko 「もこ もこもこ」. He also published picture books for toddlers and purely absurd illustrated books.

‘For me, the world we live in today is fundamentally absurd. We have become so accustomed to the rigidly defined words used by newspapers and magazines that we have come to believe that this is what language is. We should remember that originally, words have no meaning. Thus, our thinking could unfold freely. I’d like to break this value system where what doesn’t make sense is considered worthless, and what makes sense is highly regarded.’

Shuntaro Tanikawa naturally wears form-fitting T-shirts and sweaters, giving him an air of elegance. Whether discussing language or his childhood during the war, he speaks slowly and courteously. Always, he appears as a gentleman.

On shelves alongside cherished trinkets beloved by his father and various objects, he has delicately placed wildflowers from his garden. Although he grew up in Tokyo, he has regularly visited his second home in Kita-Karuizawa since childhood, and one can sense his deep affection and respect for nature.

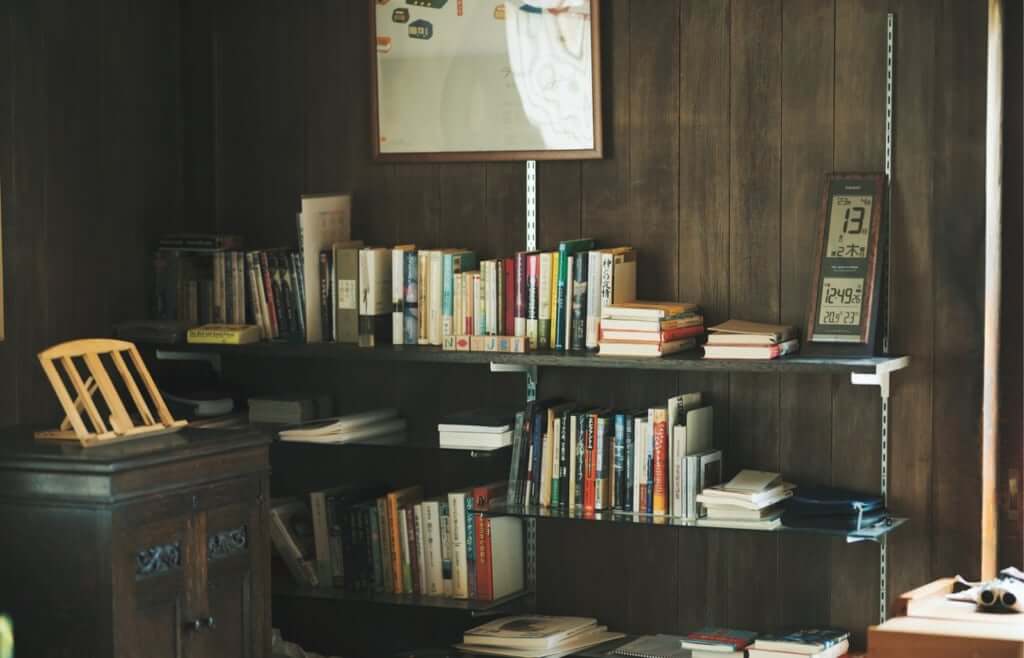

The house features a library, but bookshelves have expanded into the bedroom and hallways. Scattered around the living room are mostly recent books.

‘If, originally, language had no meaning,

it is still a tool of great delicacy.’

‘What is language?’ we asked him once more.

‘It’s difficult to express in a single word, but I believe it’s a tool of great delicacy. It’s like saying a ‘tonkachi’ トンカチ (a hammer) is a ‘kanna’ カンナ (a plane). However, the latter is actually a much finer, subtler tool. With this tool called language, humans understand each other, argue, or draw closer. Nevertheless, one should not forget that in the background, humans are made of flesh and can also perceive the sensation, the texture of language.’

He doesn’t view language as a bearer of meaning alone but also as something with a texture that can be felt. Is it because he has always sensed and accepted that our world is devoid of meaning? Since its release in 1977, Moko Mokomoko has remained a bestseller, with over 1.5 million copies sold. Even though it may seems like nonsense, the deliberate absurdity within Shuntaro Tanikawa’s work has surely resonated with many.

His favorite binoculars are placed near the window. ‘This way, I can observe birds in flight and flowers in full bloom.’ Bathed in soft light, time flows peacefully in Shuntaro Tanikawa's home.

Since the advent of word processors, Shuntaro Tanikawa prefers typing his texts rather than writing them by hand. He accomplishes poem composition, manuscript writing, and editing work on a Mac computer. Various magnifying glasses of different sizes are lined up on his desk. ‘Since my eyesight has declined, I absolutely need them.’

Shuntaro Tanikawa’s favorite word is 「好き」 ‘suki’, meaning ‘to love’. Within the exhibition, one could see his latest work, themed around the word 「すき」 ‘suki’, titled The Alphabet of Love 「すきのあいうえお」. Starting with the first letters of the Japanese syllabary, Shuntaro Tanikawa wrote about what he loves, creating assembled photos on slides to form a visual masterpiece.

‘In a single sound, you can name something with multiple meanings. To truly change things, time is needed, and this time I once again realized the all-encompassing power of language. What is truly impossible becomes achievable. Consequently, it’s also something to be wary of.’

From nothingness, language can describe and create everything from scratch. Thus, The Alphabet of Love 「すきのあいうえお」 is a work that gives shape to all the possibilities of language. To conclude, we asked Shuntaro Tanikawa about the word 「すき」 ‘suki’.

‘In summary, 「すき」 ‘suki’ is love. Isn’t love all we need, as the Beatles said? 「すき」 ‘suki’ is the word influenced by how humans fundamentally lead their lives. For me, it evokes the sensation of ‘basic Japanese language‘.‘

To live is to experience the physical sensation of reality. In our quest for the language woven by Shuntaro Tanikawa, we remembered the sensation of the universe that we had lost.

As a poet and author of illustrated books, Shuntaro Tanikawa has created numerous works in this house. From his youth to today, he has continually pondered these eternal questions, ‘When is now?’ ‘Where is here?’

Pen Magazine, July 2023 issue

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.