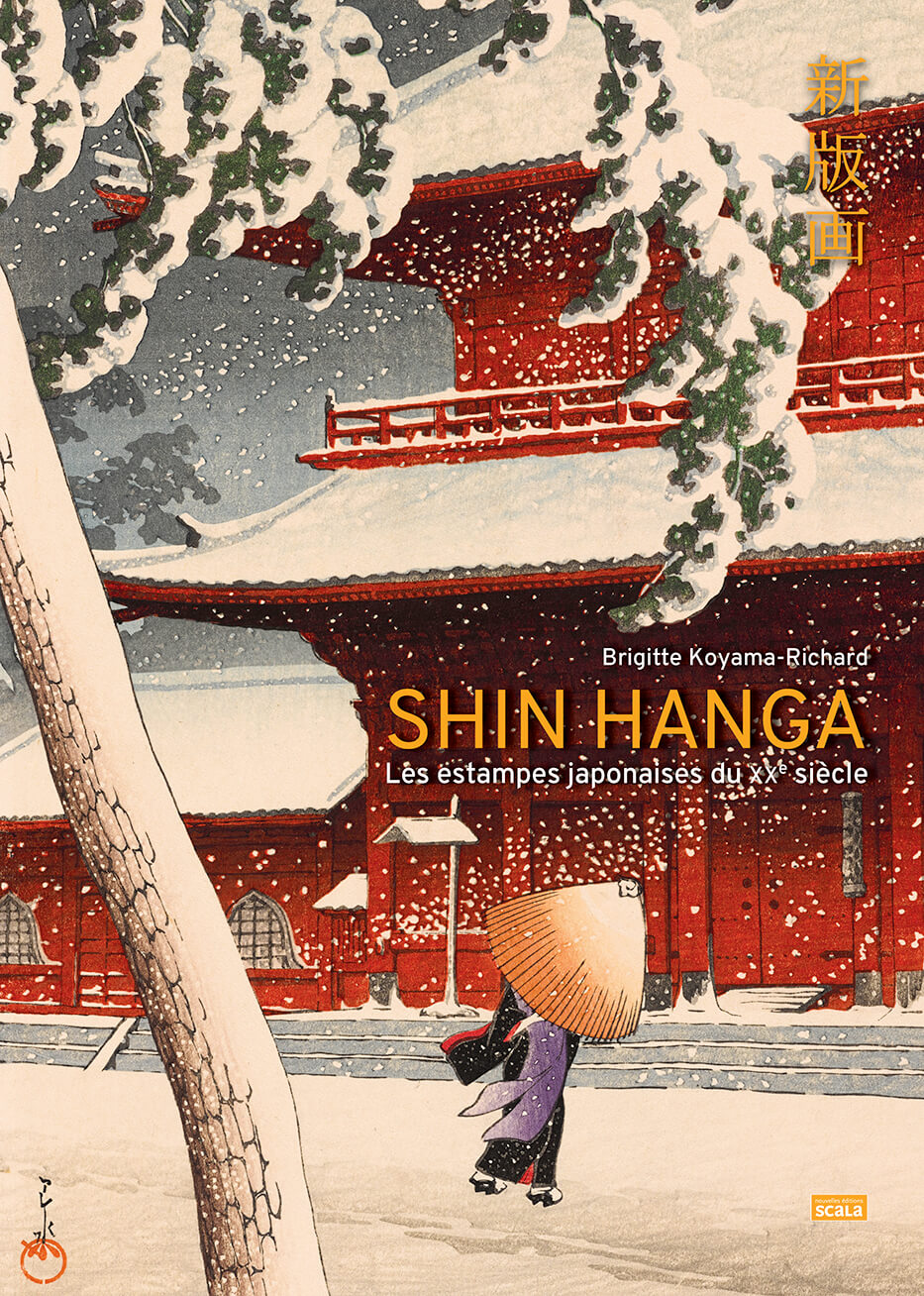

Shin-hanga, Breathing New Life into Prints in the 20th Century

In this book, Brigitte Koyama-Richard analyses a pictorial movement that revived wood engraving long after its golden age.

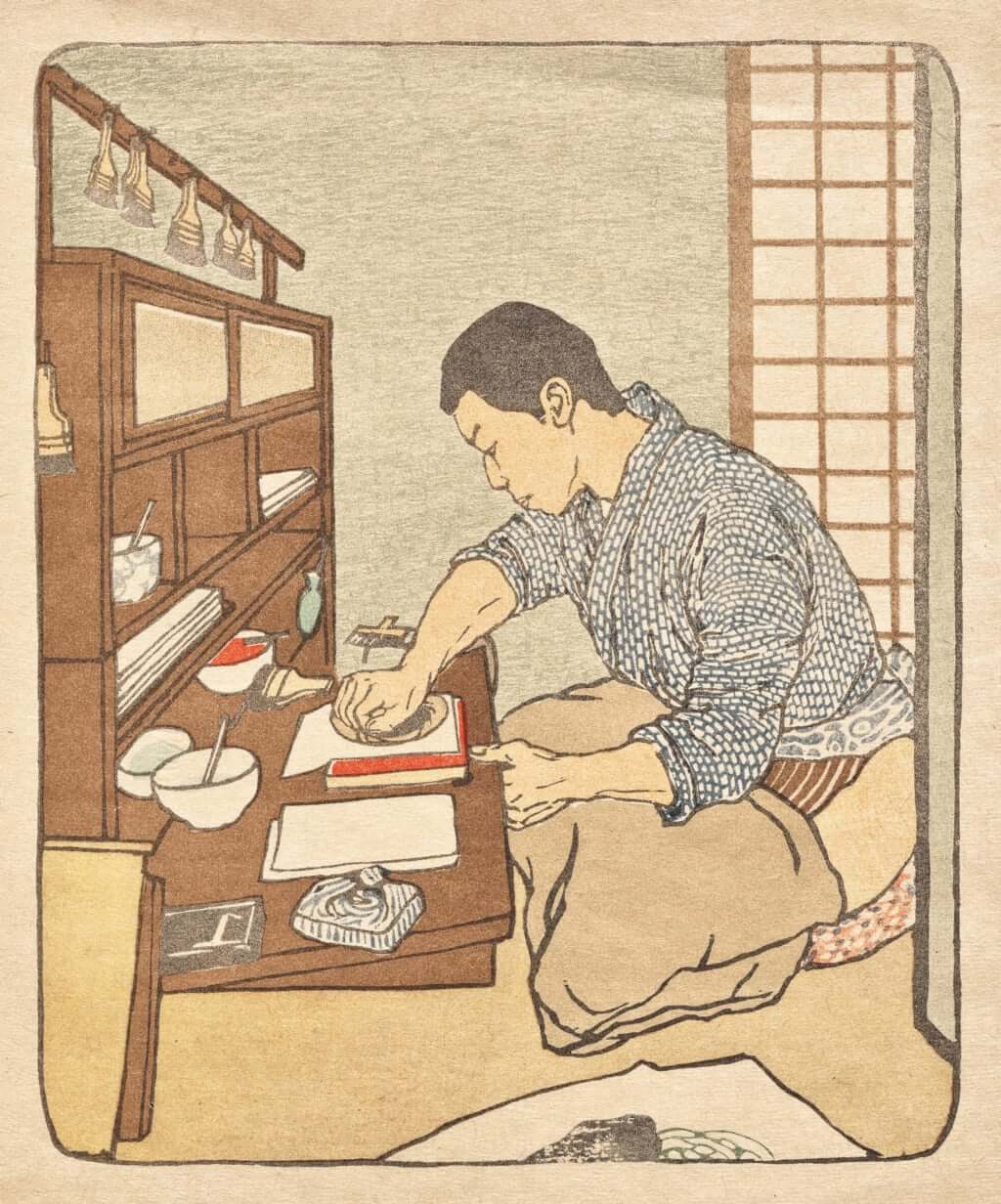

Emil Orlik, ‘Nihon no surishi (A Japanese printer)’, 1901. Lithograph, 19.3 x 15.6 cm (detail). Ph. © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Following Animaux dans la peinture japonaise (‘Animals in Japanese Painting’) (2020), author Brigitte Koyama-Richard released a high-quality work dedicated to a Japanese artistic movement, Shin hanga : Les estampes japonaises du XXe siècle (‘Shin Hanga: 20th-century Japanese Prints’) (2021). This movement, also known as ‘new prints’ or ‘pictorial revival’, developed between 1912 and 1950.

Through over 300 richly coloured illustrations, the writer presents the different artists, both from Japan and overseas, who dedicated themselves to the movement, but also the numerous themes examined (female beauty, kabuki theatre, landscapes).

Resurgence of Japanese prints

With the opening up of Japan’s economy in 1853, as well as the frenetic modernisation of the country from the 1870s onwards, ukiyo-e prints (‘‹pictures of the floating world’ in Japanese) struggled to compete with photography, lithography and other forms of prints brought over by Westerners.

Japanese businessman Shozaburo Watanabe decided to give a second life to this pictorial art by creating a new style of xylography, Shin-hanga. With the help of young artists and artisans, 2000 prints were produced in the first half of the 20th century. Thus, enthusiasts and collectors from all over the world were attracted to the movement.

Nowadays, the Watanabe company, run by the grand master’s grandson Shoichiro Watanabe, still sells this style of painting. ‘I would be happy if the Shin-hanga prints created a century ago still existed in 100 or 200 years’ time’, reveals Shozaburo’s successor in an exclusive interview with Brigitte Koyama-Richard that can be found in her book.

Priority given to the atmosphere

The Shin-hanga artistic movement reflects the evolution of Japanese society, shaken up by the arrival of Western codes, and the syncretism of two diverging cultures. This renewal does not betray the Japanese spirit; on the contrary, the traditional themes of ukiyo-e are revived.

Unlike prints from the Edo period (1603-1868), which excelled in popular themes, this movement pays particular attention to the atmosphere. Thus, the artists, inspired by impressionists, do away with technical constraints and integrate Western elements. Shadow and light effects appear in the prints. The sun shimmering over a snowy field, morning mists evaporating from a lake, the glow of streetlights reflected on the damp streets…

These effects were previously unheard of in Japanese art. ‘Since the end of the Edo period, artists had developed a passion for chiaroscuro, Western perspective and the expression of relief, and their attempts resulted in the Meiji era’, Brigitte Koyama-Richard explains in her book.

Shin hanga: Les estampes japonaises du XXe siècle (‘Shin Hanga: 20th-century Japanese Prints’) (2021), a book by Brigitte Koyama-Richard published by Nouvelles éditions Scala (not currently available in English).

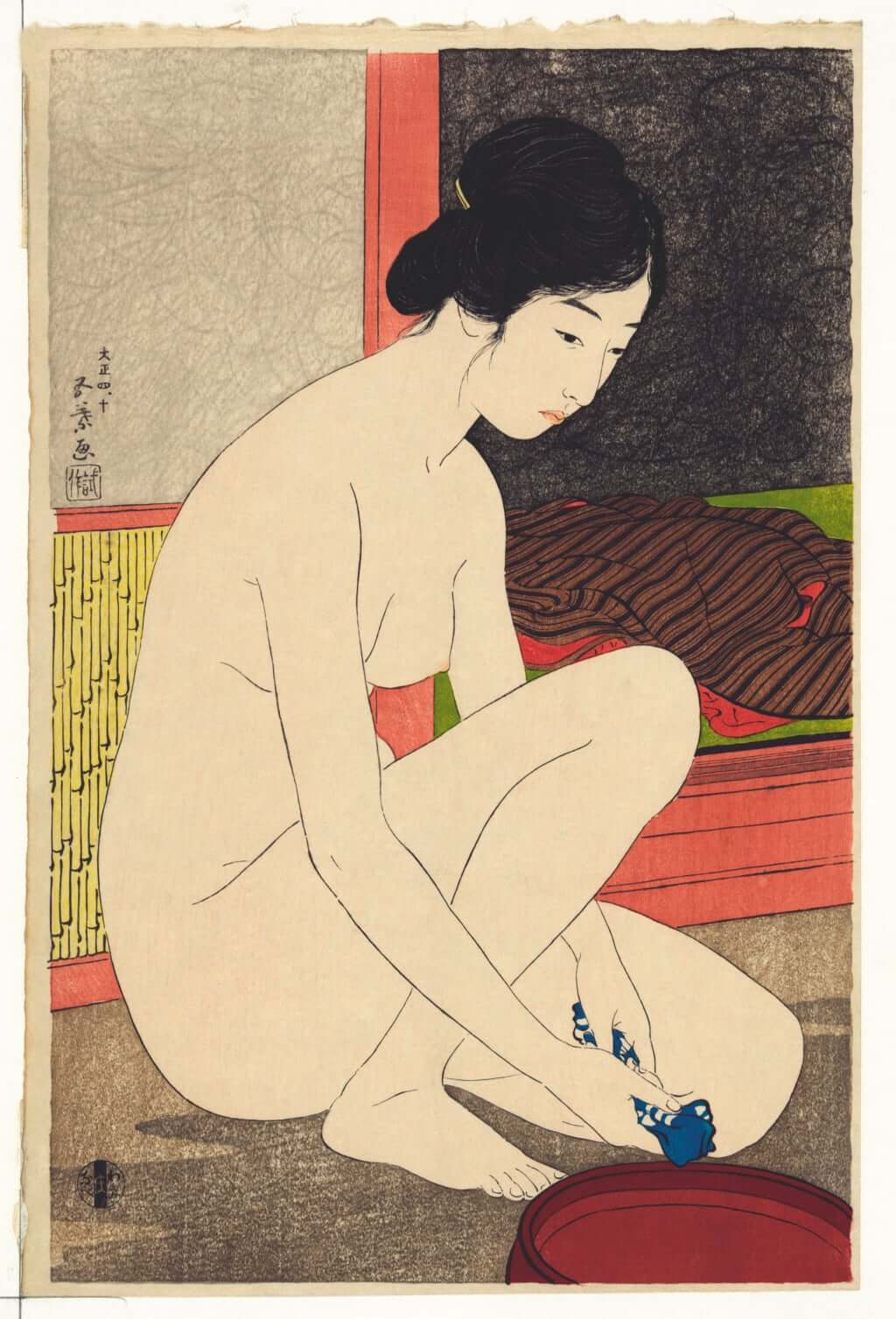

Hashiguchi Goyô, ‘Yokujô no onna (Woman after a bath)’, 1915. Woodblock print, 40.1 x 26.1 cm. Ph. © Washington, Library of Congress.

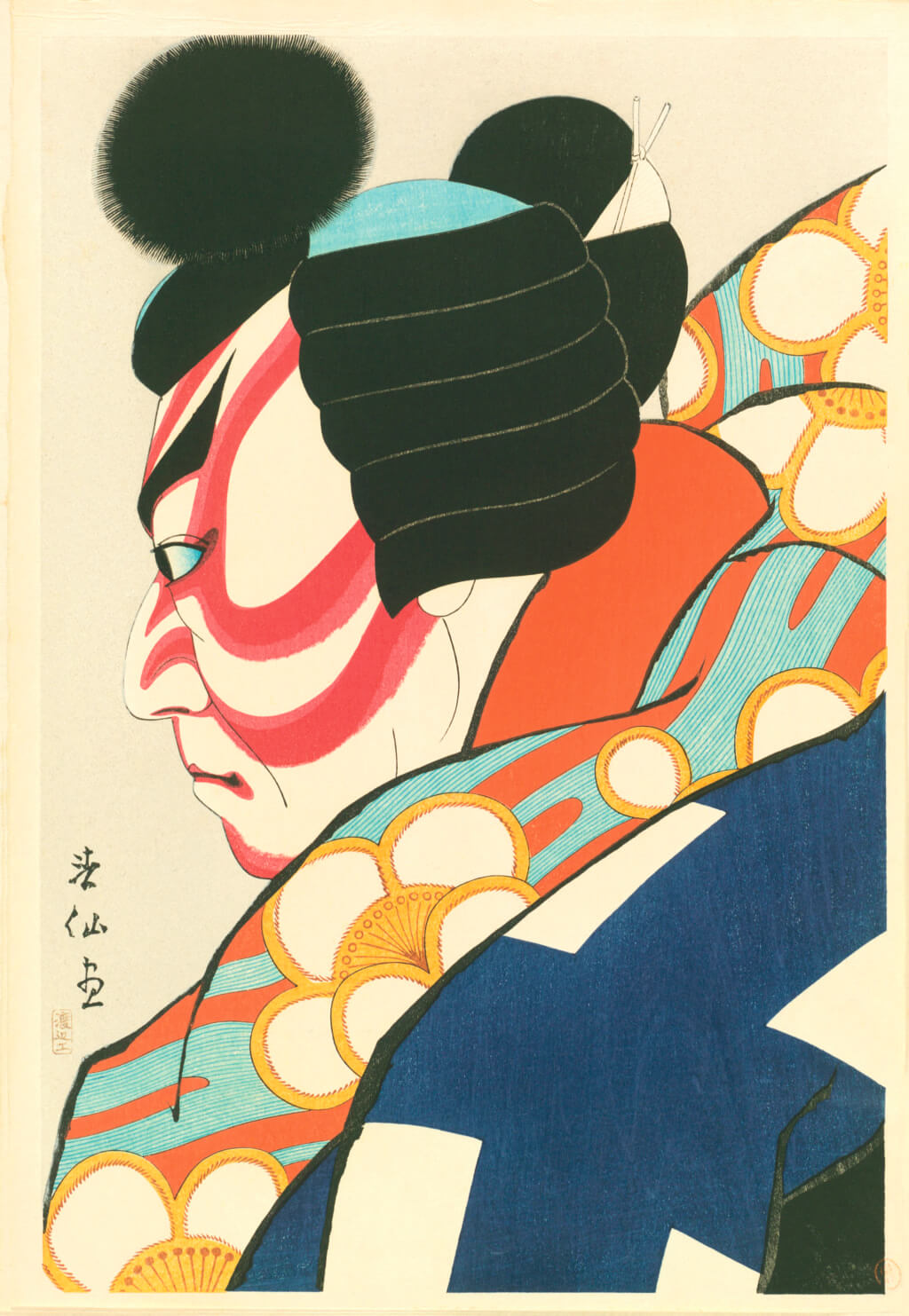

Natori Shunsen, ‘Nanadaime Matsumoto Kôshirô, Umeô, Sôsaku hanga Shunsen nigao-e shû (Matsumoto Kôshirô VII Matsumoto Kôshirô I playing the role of Umeô. Creative prints. Collection of portraits of actors by Shunsen)’, 1926. Woodblock print, 38.1 x 25.8 cm. Publisher: Watanabe Shôzaburô. Ph. © Tokyo, National Diet Library.

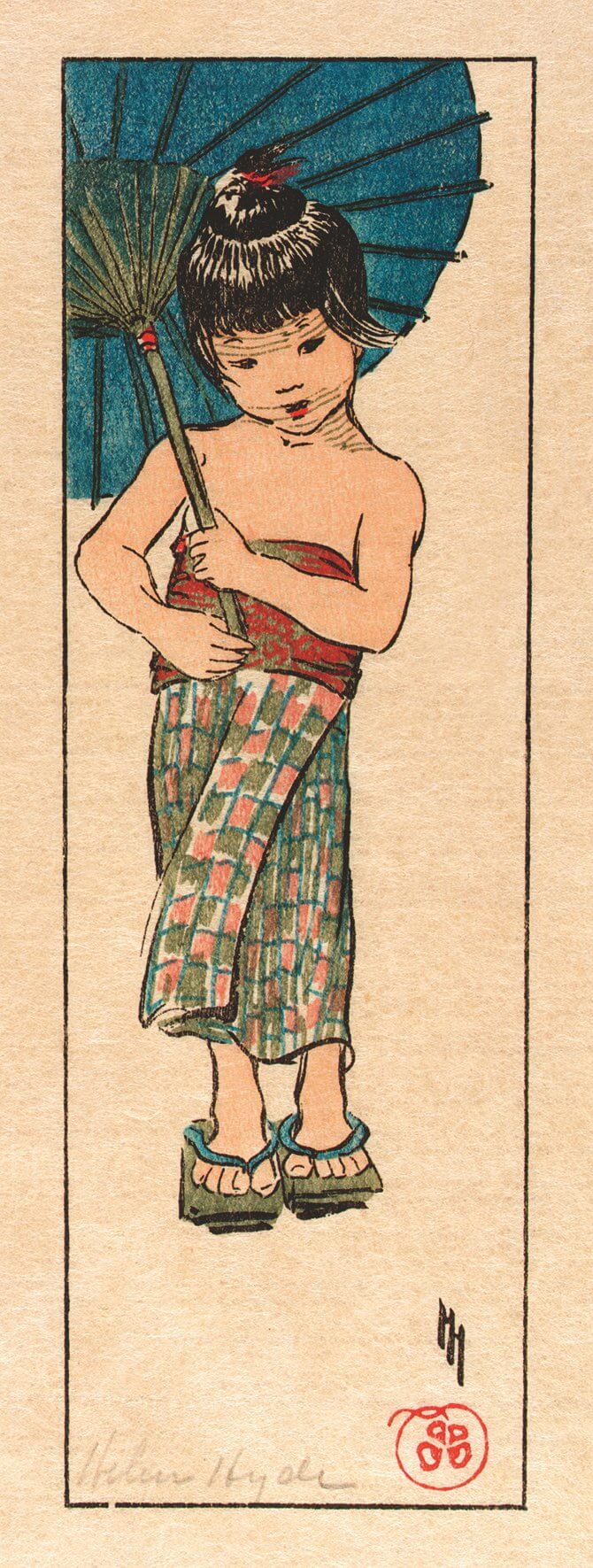

Helen Hyde, ‘A Summer Girl’, 1905. Woodblock print, 18.5 x 6.0 cm. Ph. © Washington, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Kawase Hasui, ‘Matsushima Futagojima (Matsushima Futagojima)’, 1935. Woodblock print, 23.9 x 36.1 cm. ‘Hanga shû 2 (Album of prints 2)’, Watanabe hanga ten. Publisher: Watanabe Shôzaburô. Ph. © Tokyo, National Diet Library.

Kawase Hasui, ‘Tôkyô nijû kei, Zôjôji Shiba (Twenty Views of Tokyo. Zôjôji Temple in Shiba)’, 1925. © Nouvelles Éditions Scala, 2021.

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.