To spark interest in Mingei among clients initially drawn to Scandinavian design, they developed motif-free yachimun (Okinawan ceramics). When they presented this idea to artisans, some were skeptical, but through in-depth discussions and a clear vision, they managed to win them over. These exclusive, understated pieces quickly gained popularity. By adapting Mingei to the needs and sensibilities of their time, Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura multiplied custom collaborations and helped redefine the image of this traditional craftsmanship.

Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura: Redefining the Spirit of Contemporary Mingei

The founders of MOGI Folk Art breathe new life into the traditional Mingei craft, while adapting it to today’s lifestyles.

Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura, owners of MOGI Folk Art, offer an eclectic selection ranging from furniture and ceramics to clothing and artworks, without limiting themselves to a specific genre.

A century has passed since the birth of the Mingei movement. Over this time, lifestyles have evolved, and so has the perception of this craft. Revisiting Mingei in a contemporary context means embracing the creative freedom that characterized its origins. By doing so, we can deepen and expand our appreciation of this timeless art form.

‘The key is to ask yourself if an object genuinely appeals to you,’ explains Keiko Kitamura of MOGI Folk Art, a driving force behind Mingei’s current resurgence. ‘The idea of ‘functional beauty’ is, of course, important, but reducing Mingei to purely utilitarian objects would be a mistake. We also select pieces that captivate the eye.’

One concept often associated with Mingei is yō no bi—the beauty of utility. While this principle is central to its aesthetic, overemphasizing it risks confining Mingei to a rigid framework, far from its original spirit of freedom and spontaneity. In truth, Mingei shines in its diversity, offering space for individual interpretation and expression.

Since the late 1990s, Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura have demonstrated how to seamlessly integrate Mingei into modern life. Their approach respects its history while thoughtfully adapting it to contemporary needs.

The couple’s journey into the world of Mingei began with the iconic ‘Butterfly Stool’ designed by Sōri Yanagi. Both had started their careers in the 1980s as fashion buyers for the London office of BEAMS, the celebrated Japanese select shop. In the mid-1990s, they launched BEAMS Modern Living, a homewares line that championed Scandinavian design from the 1940s to the 1960s, sparking a wave of Nordic design appreciation in Japan. Amid this, they incorporated the ‘Butterfly Stool’ into their selection.

‘The Butterfly Stool is a quintessential piece of Japanese mid-century design. While flipping through vintage European interior design magazines, we noticed it featured repeatedly. When we discovered it was designed by Sōri Yanagi, we decided to visit his studio upon returning to Japan,’ they recall.

Over time, they built a relationship of trust with him, which they continued to deepen even after securing the distribution of the ‘Butterfly Stool.’ At the time, Sōri Yanagi was the director of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Nihon Mingei-kan), and they visited it many times, drawn in by the richness of the Mingei movement initiated by his father, Sōetsu Yanagi.

‘Mingei is what the people of a region create using local materials to meet the needs of their community. Today, the movement of people and objects across the world has made local specificities less visible. Yet, there is no other country in the world where local craft traditions are as well preserved as in Japan,’ explains Terry Ellis.

Impressed by their discerning eye and enthusiasm, Sōri Yanagi opened his personal collection to them and introduced them to artisans across Japan. On one occasion, he even inscribed a recommendation on the back of his business card, a rare gesture they treasure to this day.

This pivotal encounter with Sōri Yanagi inspired them to travel across Japan, visiting the workshops of local artisans. At every step, they engaged in meaningful dialogue with the creators, selecting only the pieces that deeply resonated with their sensibilities to then share them with the world.

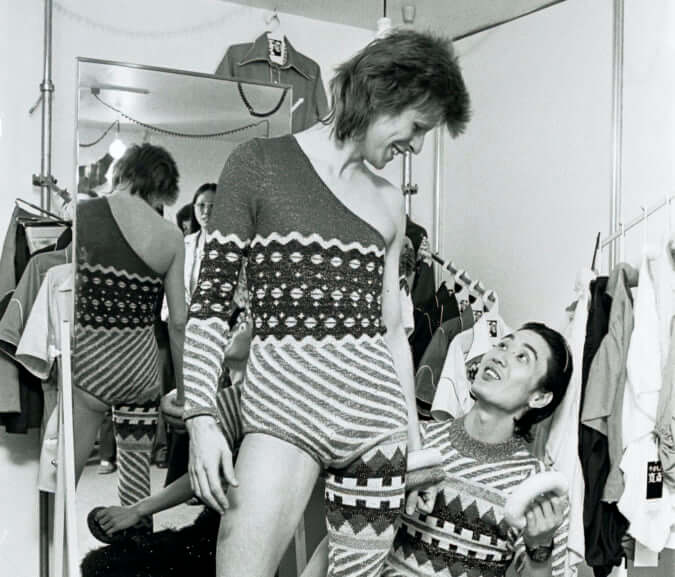

Right: Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura visit the workshop of Osamu Matsuzaki, a wood and lacquer artisan based in Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture. Having been interested in Mingei for nearly 30 years, they have built strong, trusting relationships with artisans across Japan by visiting them regularly and engaging in sincere dialogue. Left: Terry Ellis shares his ideas at Kimano Tōki workshop in Mashiko, where a couple of artisans trained in Okinawa continue to produce ceramics. Photo credits: MOGI Folk Art

‘In the homes of the great Nordic designers, there were always Mingei objects’

‘There is no other country in the world where local craft traditions are as well preserved as in Japan,’ says Terry Ellis.

Inside MOGI Folk Art, Mingei pieces sit alongside folk art, vintage objects, apparel, and original creations. This eclectic mix embodies the contemporary spirit of Mingei that Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura have cultivated since founding fennica at BEAMS in 1997. This sub-label blends Japanese craftsmanship with modern design—a vision shaped by their earlier experiences at BEAMS Modern Living.

‘When we started working with Nordic design at BEAMS Modern Living, we incorporated the ‘Butterfly Stool,’ which led us to meet Sōri Yanagi and expand our interest in Mingei. While visiting Scandinavian countries, we noticed that in the homes of great Nordic designers, there were always pieces of Mingei present. For instance, Shōji Hamada’s plates were often on display in their homes. These designers appreciated Mingei and surrounded themselves with such pieces. At Hans J. Wegner’s home, there were straw-woven shoes and straw coats from Japan’s snowy regions. They collected these items simply because they found them beautiful. These objects were seamlessly integrated and displayed within the clean, precise interiors characteristic of Scandinavian design,’ recounts Keiko Kitamura.

This harmony between Nordic design and Mingei inspired them to introduce Japanese craft objects at BEAMS Modern Living. Initially, however, they faced challenges. In 1997, as Scandinavian design gained popularity, customers were drawn to clean-lined white ceramics and sleek glassware. The bold, rugged pottery of Okinawa, for example, failed to resonate.

‘At the time, Mingei was seen as something for the older generation—not as something that could fit into a modern lifestyle,’ Keiko Kitamura recalls.

Their efforts eventually bore fruit: by the early 2000s, their shop and Mingei itself began to gain recognition, laying the groundwork for the growing popularity this art enjoys today.

A black Korean ceramic ‘tokuri’ sake bottle from the Joseon period. Once owned by Janet Leach, wife of Bernard Leach, this piece was acquired in London.

A condiment container by Shōji Hamada. Initially presented as an anonymous piece when discovered in Mashiko, Terry Ellis was convinced it was the work of Shōji Hamada. His attribution was later confirmed by Tomoo Hamada, the artist’s grandson. The pot’s unusually large size for Japanese use reflects the influence of foreign objects observed by Shōji Hamada.

A tea bowl by Kanjirō Kawai. Both utilitarian and remarkably beautiful, this bowl perfectly embodies Kanjirō Kawai’s distinctive style.

‘The things you acquire instinctively always integrate naturally into your life’

‘If something speaks to you, just buy it. Your sensibility will naturally evolve through your choices,’ advises Keiko Kitamura.

‘What matters most is that you genuinely love an object and want to live with it,’ Keiko Kitamura emphasizes. ‘If it feels more beautiful displayed, then display it. And if your tastes change, perhaps you’ll want to seek out an earlier piece by the same artisan. By tracing these creative lineages, Mingei becomes even more fascinating.’

She encourages people to follow their instincts when buying. By collecting objects that resonate with them, individuals naturally refine their sensibilities over time. This philosophy is evident in the carefully curated selection at their two shops—and one can only imagine the vast collection in their home.

‘There’s no need to think, ‘What’s the point of owning so many things?’ Instead, create a space where each piece can shine. When hosting guests, we rearrange displays or select tableware to suit the meal. It sparks conversations. And for those worried about small spaces, try adding larger pieces. Paradoxically, it makes the space feel bigger and more balanced than cluttering it with small items,’ Keiko Kitamura advises.

In the 1990s, when few paid attention to Mingei, Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura saw its beauty and relevance. They’ve spent decades demonstrating how this craft can enrich daily life—not by replicating the past but by staying attuned to contemporary needs. Their driving force? Loving what they choose and trusting their own sensibilities.

‘When buying something, don’t over-research it on your smartphone,’ Terry Ellis suggests. ‘Trust your intuition. The things you acquire instinctively always integrate naturally into your life.’

More information on MOGI Folk Art can be found on the boutique’s website.

A plate by Kashin Teruya, representative of Okinawa’s ‘yachimun’ style. Trained under master artisan Eishō Kobashigawa—one of the ‘Three Men of Tsuboya’ (in Naha, Okinawa)—Kashin Teruya has been producing pieces for nearly 40 years since opening his own workshop in 1985.

A stool from Kenya. A rare piece in the collection of Terry Ellis and Keiko Kitamura, which primarily consists of West African artifacts.

A West African mask. ‘Japan is home to many outstanding pieces of African art. Keisuke Serizawa’s collection is a perfect example and has deeply inspired us,’ says Terry Ellis.

TRENDING

-

Hiroshi Nagai's Sun-Drenched Pop Paintings, an Ode to California

Through his colourful pieces, the painter transports viewers to the west coast of America as it was in the 1950s.

-

A Craft Practice Rooted in Okinawa’s Nature and Everyday Landscapes

Ai and Hiroyuki Tokeshi work with Okinawan wood, an exacting material, drawing on a local tradition of woodworking and lacquerware.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

David Bowie Dressed by Kansai Yamamoto

The English singer was strongly influenced by 'kabuki' theatre and charged the Japanese designer with creating his costumes in the 1970s.

-

‘Seeing People My Age or Younger Succeed Makes Me Uneasy’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.