Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

Ishiuchi Miyako. ‘Mother’s #35’, Mother’s series. Courtesy of the artist / The Third Gallery Aya.

Women, as quintessential subjects of photography, have seen their bodies magnified and objectified countless times by art. In three series by Ishiuchi Miyako, who strives to ‘capture the invisible,’ the female body shines through its absence. The photographer skillfully crafts intimate portraits of those who have passed through the objects they left behind: dresses with no hips to fill, a comb with no hair to adorn, a lipstick with no lips to color.

In Mother’s (2000-2005), ひろしま/hiroshima (2008-present), and Frida (2013), Ishiuchi Miyako reconstructs the lives of her mother, victims of the atomic bombing, and artist Frida Kahlo. The photographer, born in 1947 in Gunma Prefecture, has curated these three series, which depict the lives of women, in an exhibition titled Belongings at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles (until September 29, 2024), where she received the 2024 Women in Motion Award for Photography. An accolade she accepted as a representative of a group of Japanese women photographers who have long been sidelined in the history of their discipline, now honored in a major collective exhibition this year.

A Talent for Seeing Things Differently

In Zesshō Yokosuka Story (‘Magnificent Poem: Yokosuka Story’), the artist captured the city where she grew up from an unprecedented angle. While other photographers like Daido Moriyama and Shomei Tomatsu had already documented the military base and entertainment districts there, Ishiuchi Miyako indirectly highlighted the consequences of American occupation on the surrounding neighborhoods and their inhabitants. This was her way of reconciling with a city where numerous unpunished sexual crimes occurred. She later said that it was in this environment that she first became aware of her identity as a woman.

This realization continued to shape her as she advanced in her career. In the Japanese photography world, which she describes as a ‘boys’ club,’ Ishiuchi Miyako had to assert herself. ‘As a young woman, you fall victim to many things,’ she explains in an interview with Pen. ‘Even though I don’t consider myself a victim of misogyny, I didn’t want to be underestimated. So, I created an image of a strong woman to face men.’

The Passage of Time, Central to Her Work

Her attitude evolved as she turned forty, and the image she had created became too burdensome. She then returned to her ‘natural state.’ This return to essentials is reflected in her work through two series revealing unadorned bodies. In 1・9・4・7 (1988-1989), Ishiuchi Miyako photographed about fifty women born the same year as her, focusing unusually on their hands and feet. With Scars (1995-1996), she illuminated scars as traces of past wounds. ‘I want to represent things that have no form. Time, sadness, memories,’ she said.

The passage of time is thus central to her work. After identifying it in the knots and creases of palms and soles, Ishiuchi Miyako sought its traces in the personal effects of the deceased. ‘These objects carry the proof of a human life,’ she asserts. ‘Even after a person is gone, their shape, like a shadow, continues to inhabit their belongings.’

From 2000 to 2005, Ishiuchi Miyako attempted to reconstruct her mother’s life, who had passed away suddenly, in the series Mother’s. She pondered over the aspects of her mother’s personality that would remain forever inaccessible, such as her penchant for collecting lingerie. Her photographic approach also evolved, notably transitioning to color. This work garnered significant success, and the photographer was selected to represent Japan at the Venice Biennale in 2005. Shortly after, a publisher proposed that she photograph the belongings of atomic bomb victims from Hiroshima. Surprised to discover colorful clothes, having only seen black-and-white images of the disaster, Ishiuchi Miyako created a new color series, ひろしま/hiroshima.

‘I want to capture things as they naturally are. That’s why I switched to color. To capture the crimson of [my mother’s] lipstick,’ recalls Ishiuchi Miyako. ‘I initially started photographing the ひろしま/hiroshima series in black and white. But monochrome is heavy. And it’s not natural because we don’t see in black and white.’

Attention to Details that Constitute Women’s Lives

Later, the photographer was invited to immortalize Frida Kahlo’s personal effects, kept sealed in the artist’s bathroom at the request of her husband Diego Rivera until 2004. In Frida (2013), Ishiuchi Miyako once again revived the shadow of a past life, giving form to Frida Kahlo’s personality in a unique way, as if she had just left her corsets and boots.

This attention to details that constitute women’s lives, and the way she conveys reality by moving away from fantasies and clichés through a female gaze, suggests a feminist approach to the photographic subject. When asked about this, Ishiuchi Miyako concludes with nuance and humility. ‘I didn’t really concern myself with feminism, but the result of my work is considered as such. It’s not just about gender or feminism, but about how I lived my life. And these themes naturally permeate my daily life.’

To celebrate the extraordinary life and career of the photographer, the Rencontres d’Arles and Kering awarded her the 2024 Women in Motion Award for Photography. This prize, since 2019, honors women photographers who have made a significant impact on their discipline.

As part of their partnership, the Arles festival and the French group are also committed to promoting photographic heritage with the Women in Motion LAB, an initiative supporting research projects around female figures in photography. In 2024, the program enabled the organization of a major collective exhibition of Japanese women photographers’ work, I’m So Happy You Are Here, Japanese Women Photographers From the 1950s to Now accompanied by an unprecedented book restoring the rightful place of Japanese women artists in the history of their country’s photography.

Belongings (2024), an exhibition of photographs by Ishiuchi Miyako at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, until September 29, 2024, Salle Henri Comte.

Ishiuchi Miyako is represented by The Third Gallery Aya.

Ishiuchi Miyako. ‘ひろしま/hiroshima #37F donor: Harada A.’, Courtesy of the artist / The Third Gallery Aya.

Ishiuchi Miyako. ‘ひろしま/hiroshima #21 donor: Segawa M.’, Courtesy of the artist / The Third Gallery Aya.

Ishiuchi Miyako. ‘Frida by Ishiuchi #34’, Frida by Ishiuchi series. Courtesy of the artist / The Third Gallery Aya.

Ishiuchi Miyako at the presentation of the 2024 Women in Motion Award for Photography at the Ancient Theatre of Arles © Lisa Le Corre

TRENDING

-

Hiroshi Nagai's Sun-Drenched Pop Paintings, an Ode to California

Through his colourful pieces, the painter transports viewers to the west coast of America as it was in the 1950s.

-

A Craft Practice Rooted in Okinawa’s Nature and Everyday Landscapes

Ai and Hiroyuki Tokeshi work with Okinawan wood, an exacting material, drawing on a local tradition of woodworking and lacquerware.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

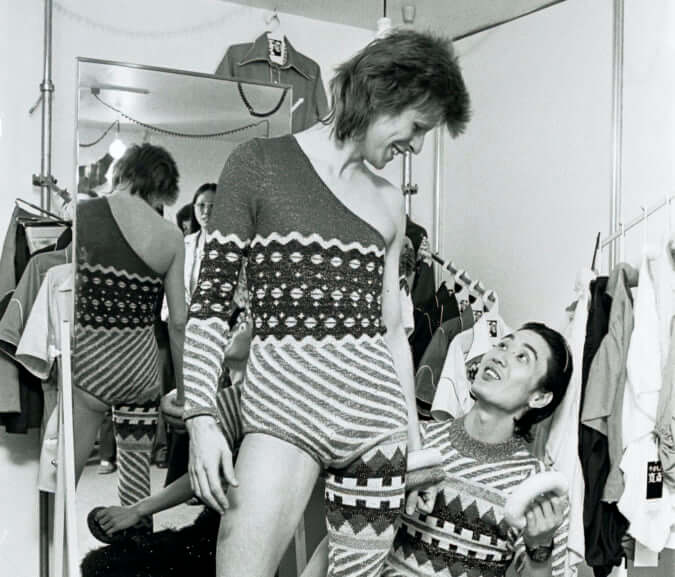

David Bowie Dressed by Kansai Yamamoto

The English singer was strongly influenced by 'kabuki' theatre and charged the Japanese designer with creating his costumes in the 1970s.

-

‘Seeing People My Age or Younger Succeed Makes Me Uneasy’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.