Modernology, Kon Wajiro’s Science of Everyday Observation

Makeup, beard shape, the organisation of cupboards, and meeting places: all of these details decipher 1920s Tokyoites.

© Kon Wajiro

Ginza, May 1925. On the avenue that links Kyobashi and Nihonbashi Bridge, a group, dispersed in the crowd with pencils and pre-filled plans in hand, notes down the different idiosyncrasies of the capital’s residents. This meticulous task was termed modernology and came from the imagination of Japanese architect and designer Kon Wajiro. The aim was to capture live, in a scientific manner, the everyday life of the residents and of this city just picking itself up after an earthquake that had hit two years previously.

Born in 1888 in Aomori Prefecture in northern Honshu, Kon Wajiro moved to Tokyo with his family while finishing his secondary-level studies and enrolled in the Tokyo University of the Arts the following year. He then went on to work at Waseda University, where he would spend his career as a professor, alongside participating in various surveys of Japan’s rural areas. After this, he undertook his own observation of the present time in the Japanese capital.

Itemising habits

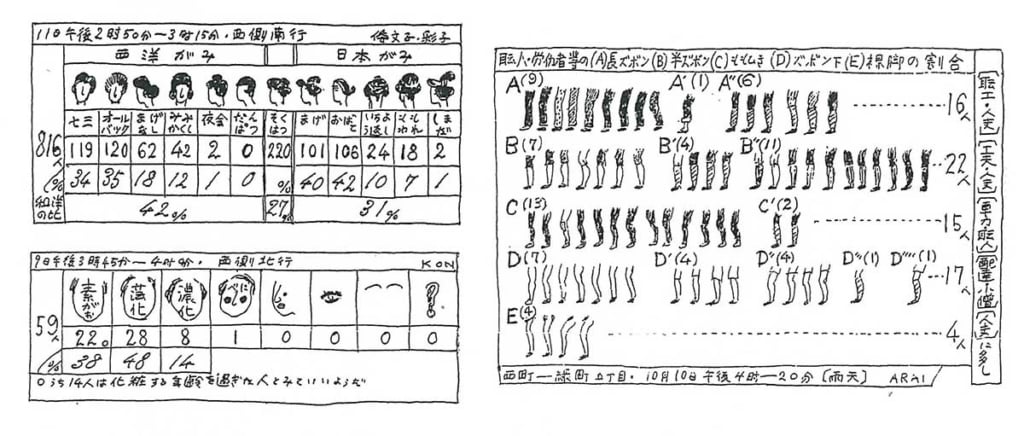

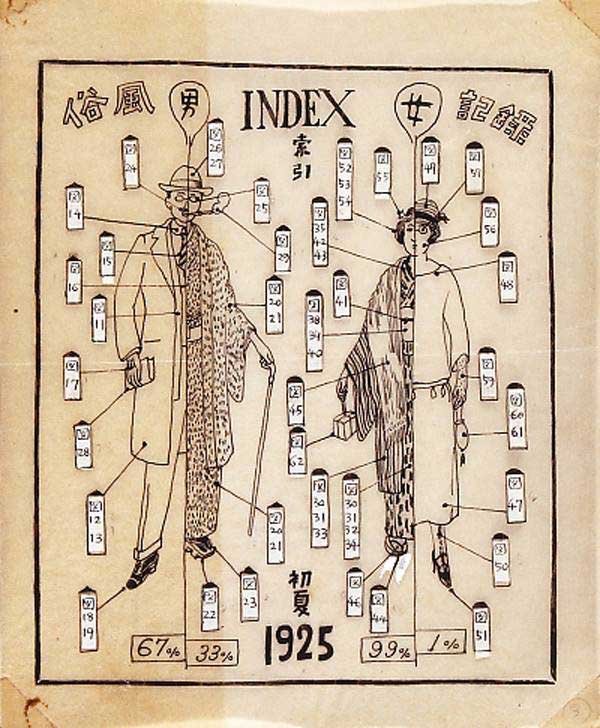

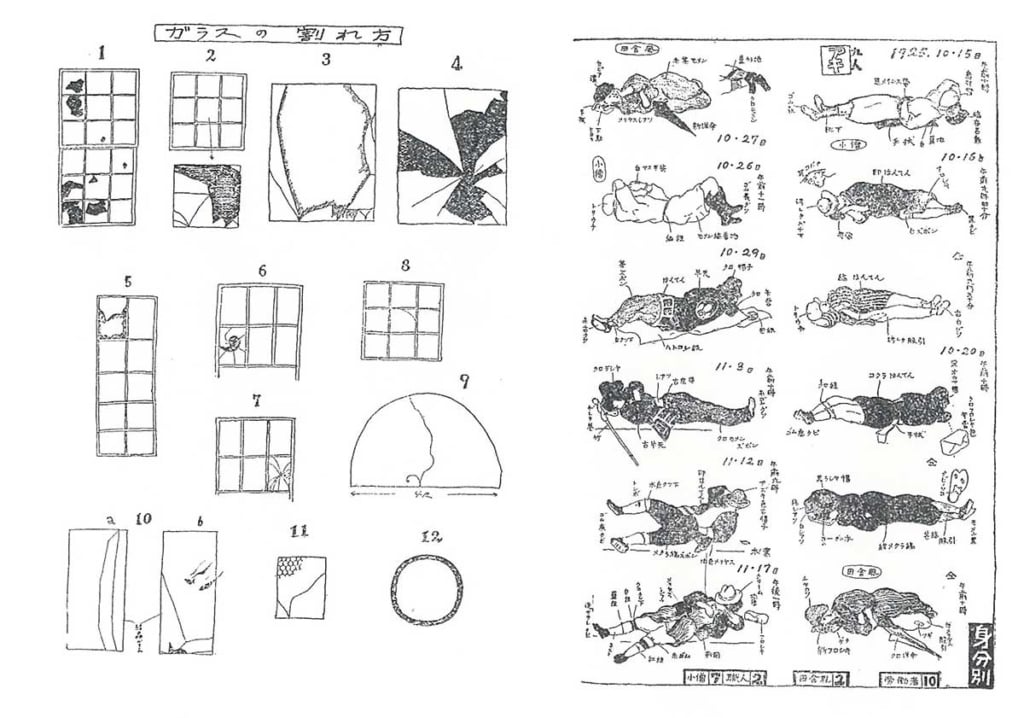

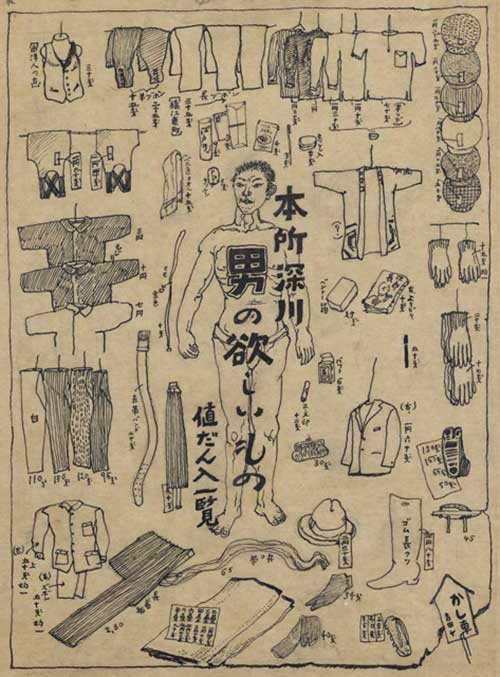

Sex, age group, makeup style, beard and moustache shape, type of kimono, length of skirt… Kon Wajiro kept a record of these details that might seem insignificant to the uninitiated. The results of this first study, which lasted four days, were published a few months later in the magazine Fujin kôron in the form of drawings, sketches, and graphics designed to offer a precise image of the Tokyoite in the spring of 1925. First termed kogengaku (science of the present), Kon Wajiro himself preferred the Esperanto term modernologio and, in 1930, wrote the manifesto What is Modernology? In this text, the architect sets out the fundamental principles of the science he sought to create, in order to note down the present and the development of the practices and lifestyles of Japanese people in the most accurate way possible.

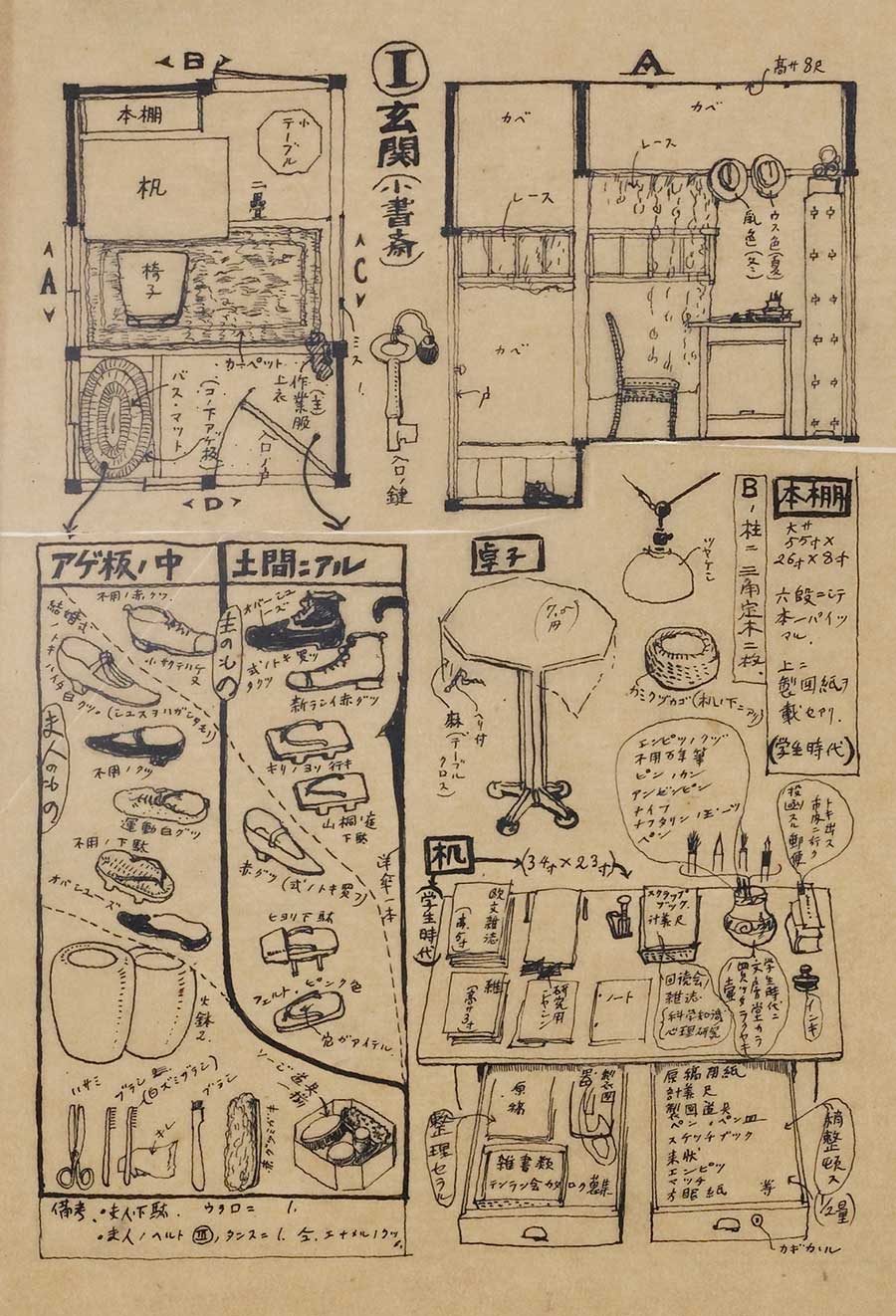

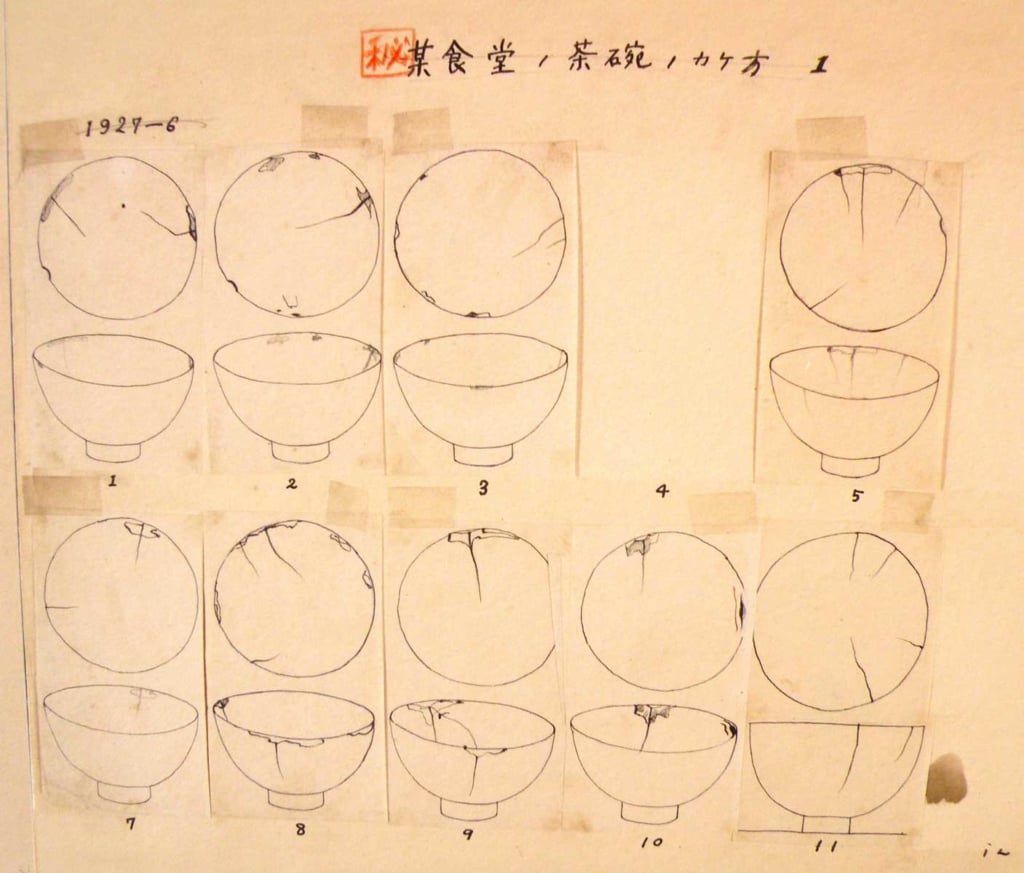

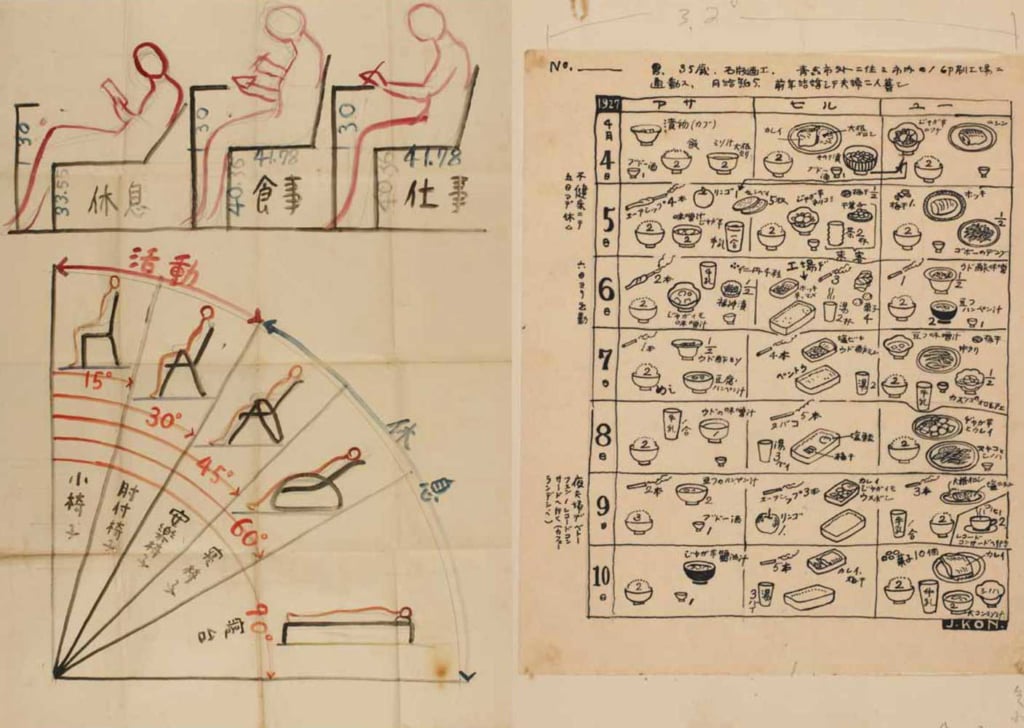

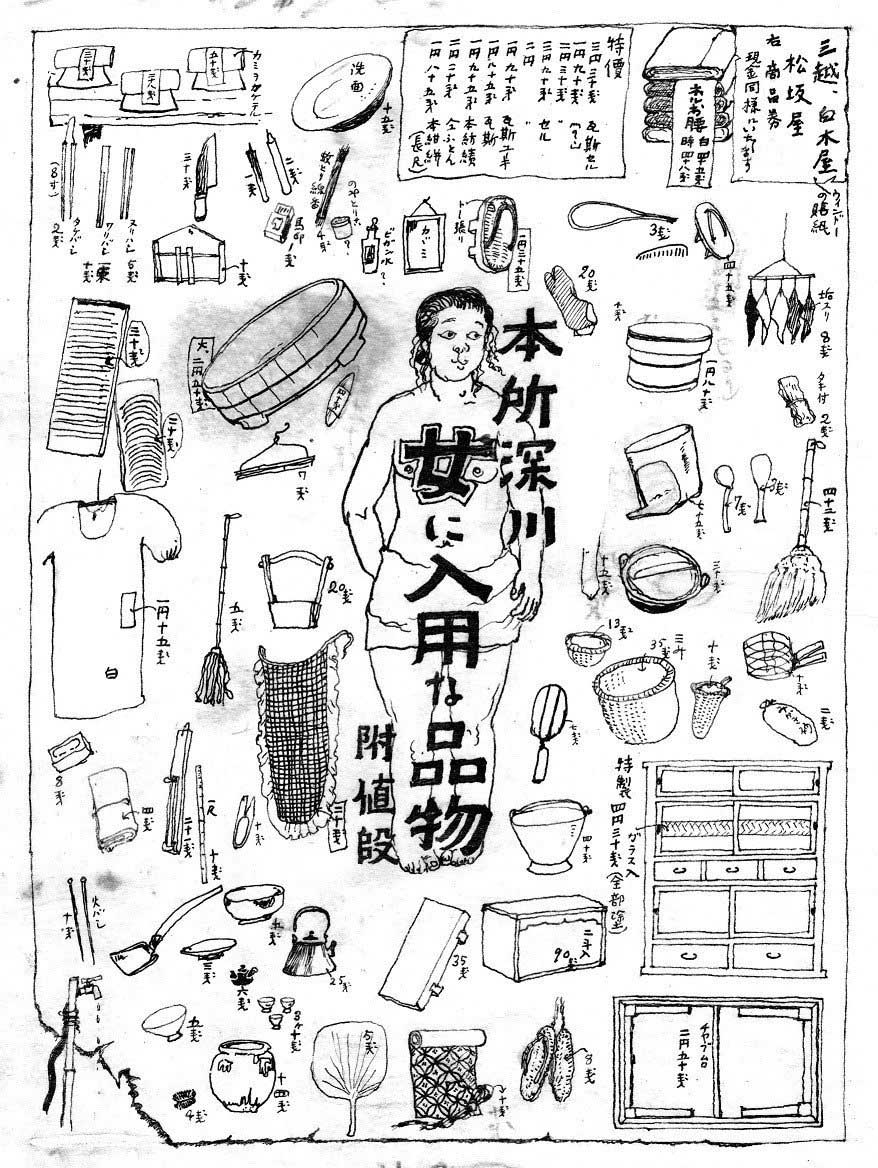

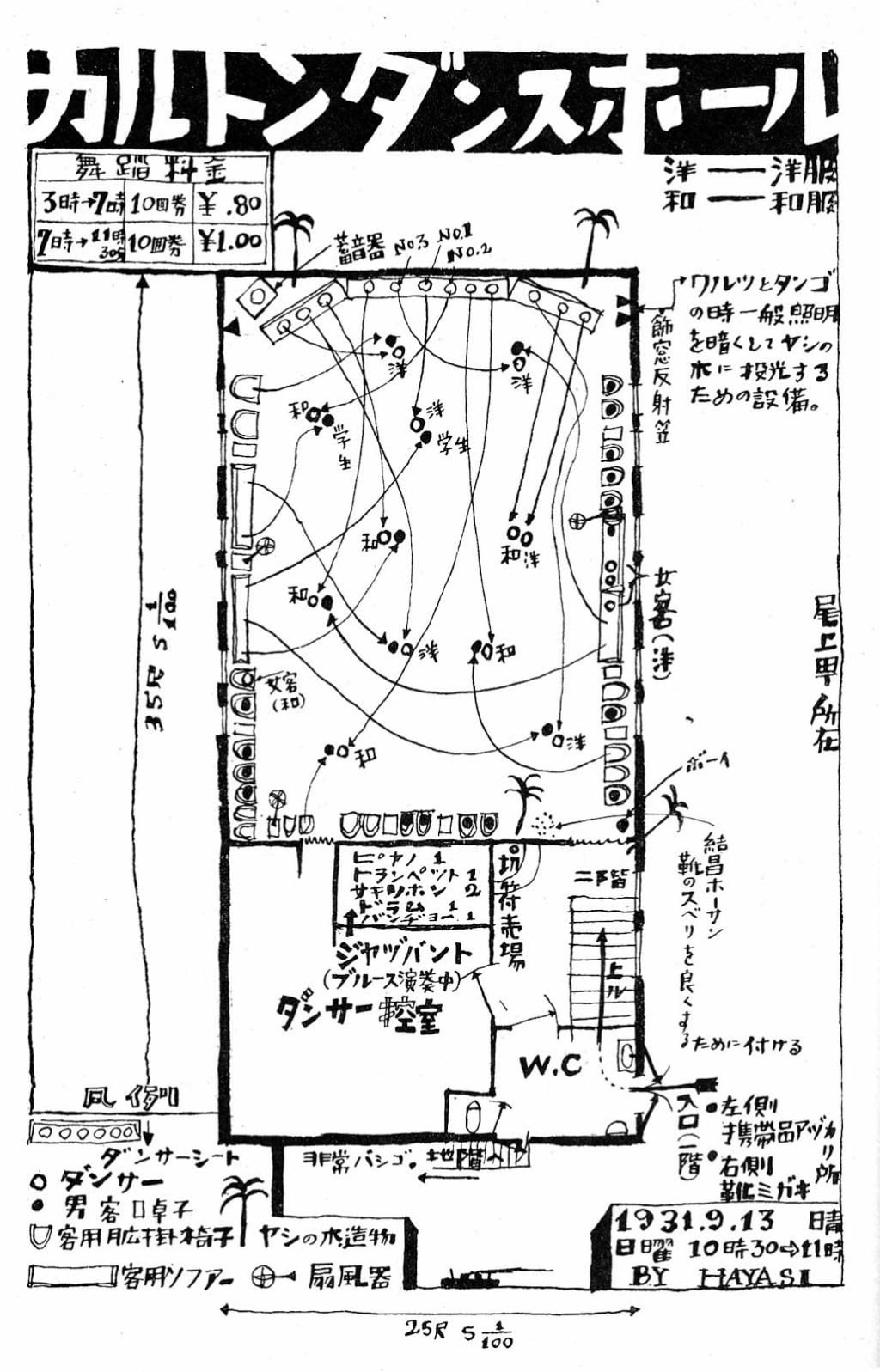

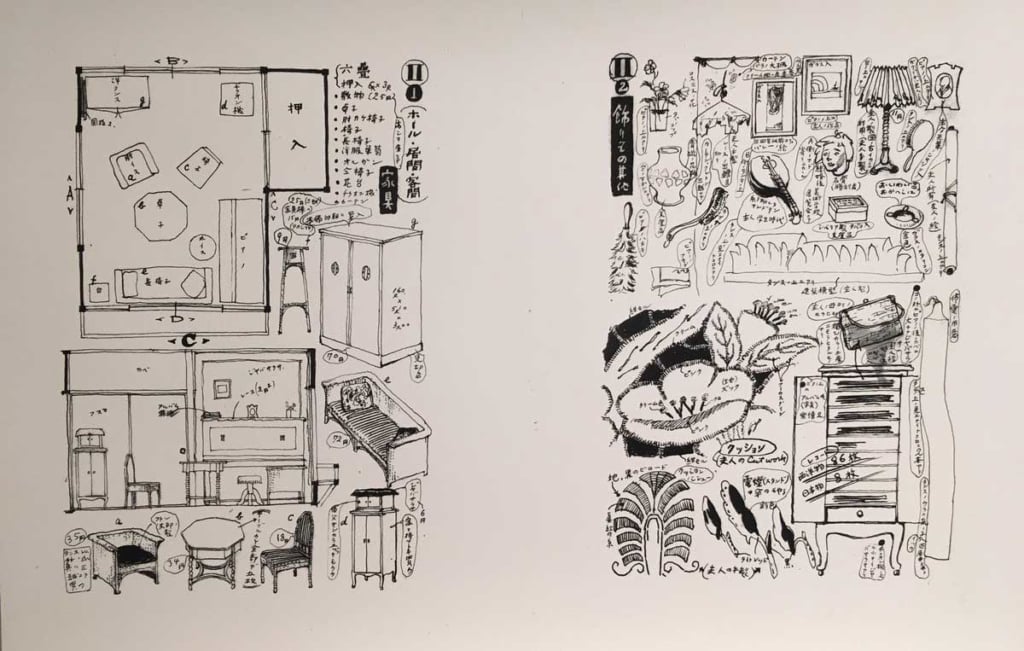

But this was just the first step for Kon Wajiro and his associates, who soon extended the protocol outside of the Ginza district and tried to capture the spirit of the time across the whole of the city. Picnic spots in parks, cracks in bowls in low-price cafeterias, the organisation of their contemporaries’ cupboards, the shape of women’s elegant hairstyles… Any excuse to observe and collect details.

Capturing the present moment

The result is a kaleidoscopic observation where the individual, seen as the sum of details, sheds light on the period in which they live in their own way. Modernology’s aim is not really an analytical one; it sees itself more as a collection of ways of being, in a given place, at a given moment and where the collection of samples has value for what it is: a set of diverse profiles which, laid end-to-end like points on a map, have no other purpose than to offer an image of the present moment.

The sketches made from these observations are thus packed with information, the clarity of the message contesting with a certain desire for detail. As well as the sketches, the architect added measurements, materials, estimated prices, numbers… and multiplied the depth of interpretation, as if to objectify the real. Although Kon Wajiro’s modernology did not survive the 1930s as a scientific discipline, this very particular way of sketching everyday life in Japan and capturing the spirit of the time continues today, as in the work of Florent Chavouet, author of Tokyo Sanpo.

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

© Kon Wajiro

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

David Bowie Dressed by Kansai Yamamoto

The English singer was strongly influenced by 'kabuki' theatre and charged the Japanese designer with creating his costumes in the 1970s.

-

‘As the Wind Stirred the Ashes, Little Gems Remained’: Haruomi Hosono by Laurent Brancowitz, Guitarist of Phoenix

Since its inception, the French pop rock band has drawn inspiration from the rich soundscapes of 1970s Japan and one of its iconic figures.

-

Mount Zao's Snow Monsters

Every year, from December to March, the slopes of this volcano are invaded by strange creatures known as 'juhyo'.

-

Ceramics, Their Creators, and Japan in Their Most Intimate Aspects

In Mexico, six Japanese artists share life experiences, relationships to nature and their ways of connecting with it.