Toulouse-Lautrec and His Japanese Influences

Inspired by his Japanese counterparts, the painter reinvented form and technique within his art and is indebted to printmaking techniques.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. ‘ELLES: the seated clowness’, 1896 © Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France

Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrait of Suzanne Valadon, completed in 1884, right at the beginning of his career, contains a small detail that isn’t immediately noticeable. The composition itself, depicting the woman entirely naked, face-on, and with a look of defiance, is enough to ruffle the feathers of any moralising observer; however, it is the mask in the background that is of particular interest. This Noh mask is not there by chance—it is a nod to Toulouse-Lautrec’s passion for Japanese art.

The work of the French painter was on display at the Grand Palais in Paris under the exhibition Toulouse-Lautrec, Resolutely Modern, until 27 January 2020. From his mastery of lithography to his representations of daily life from a naturalist perspective, the artist, born in 1864, was often strides ahead of his contemporaries. However his love of Japan was very much of his time.

The Epoch of Japonisme

It was initially Japanese ceramics, such as Imari ware, that initially made it to the West in the 17th century, followed by prints brought by Dutch traders in the early 19th century. When Japan opened its borders to the world upon the advent of the Meiji Era in 1868, a wealth of exchanges took place between Japan and Europe, with the East and its art—especially woodblock prints—now more accessible. This was the arrival of Japonisme, and the influence of Japanese art on Western writers and artists, with its influence peaking between 1860 and 1890.

Toulouse-Lautrec was one of these fans, proclaming his appreciation for Japanese influences. The exhibition at the Grand Palais includes a photo of the painter dressed in Japanese dress, sat in seiza, squinting outrageously, a look borrowed from one of the many prints that he collected.

According to Danièle Devynck, director of the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum in Albi in France, and curator of the exhibition, it is known for certain that he was in possession of a number of Hokusai manga (sketchbooks), and that he also collected woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) by Utamaro Kitagawa. He was an informed lover of Japan, reading the revue Le Japon Artistique published by Siegfried Bing.

This monthly revue, published between 1888 and 1891, reproduced images of Japanese woodblock prints and objects, Siegfried Bing being a notable importer of such goods. Between 1894 and 1895, Toulouse-Lautrec created an Art Nouveau stained glass panel for the dealer, entitled ‘Au Nouveau Cirque, Papa Chrysanthème’ (At the New Circus, Papa Chrysanthemum), referencing the ballet Papa Chrysanthemum, which takes place in Japan—a Japanese prince marries a French woman who must dance in front of the Japanese imperial court in order to be accepted. In Toulouse-Lautrec’s interpretation we see a woman from the back, absorbed by a circus.

A Renewal of Form

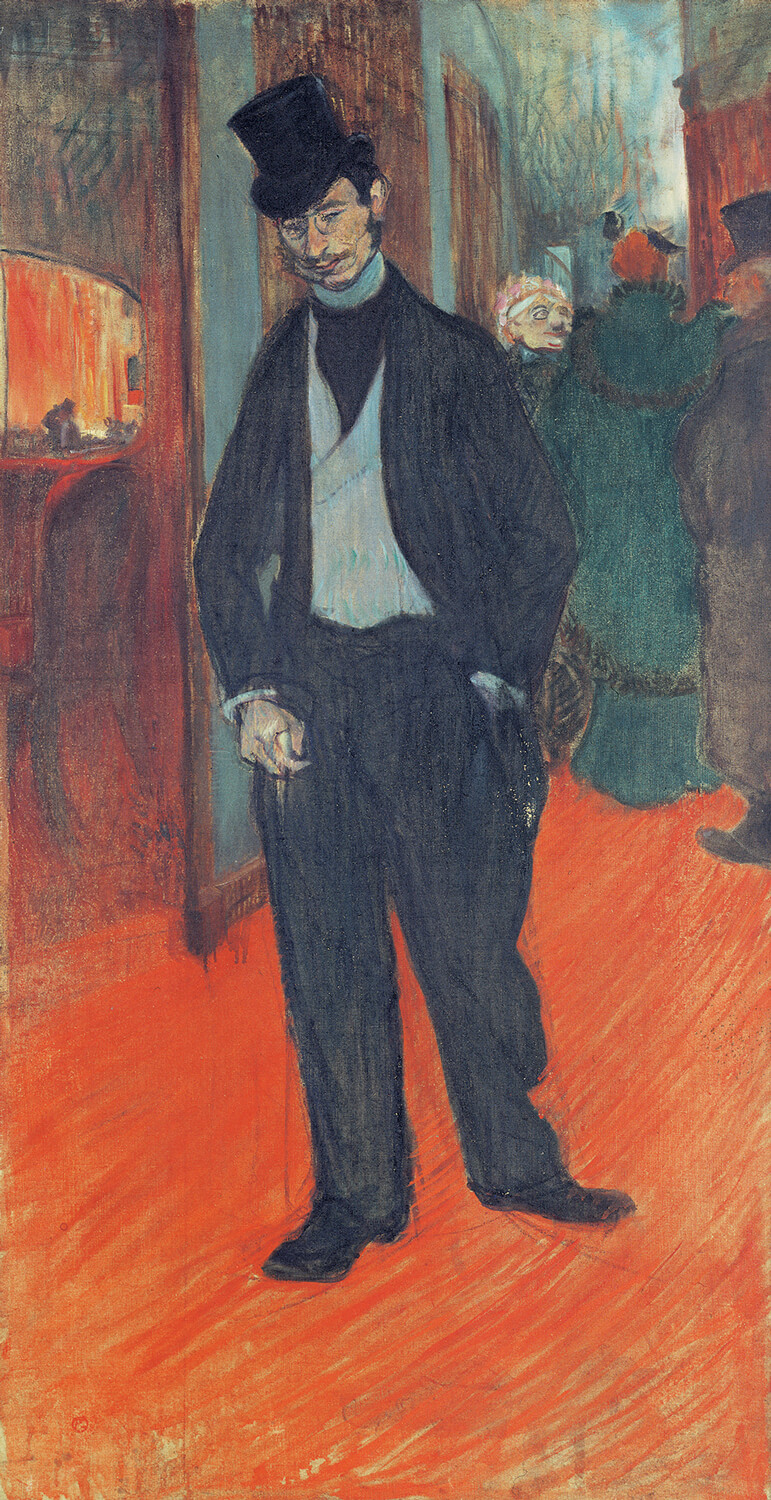

Inspired by his Japanese counterparts Toulouse-Lautrec reinvented his art. His admiration for Japan shows through in multiple ways. First and foremost it can be seen in the vertical format of his paintings, reminiscent of kakemono. The series of portraits of dandies on display at the Grand Palais is one of the most obvious examples, notably the painting of his cousin, ‘Doctor Tapié de Céleyran’ (1893-1894). This is a direct reference to the Japanese vertical format, as are the use of kakemono in the background of the ‘Portrait of Doctor Henri Bourges’ (1891).

Beyond just the format, from Japan Toulouse-Lautrec also borrowed printmaking techniques. His lithographs, which he spent years perfecting, are now considered the apex of his production. He produced over 400 during his career, up until when they had been more or less looked down upon by artists.

According to Danièle Devynck, Japanese art seemed to provide responses to the artistic questions Toulouse-Lautrec was asking himself at the time. These synthetic images, depicted in Japanese printing with their flat colours and on the diagonal, provided a new compositional format.

Ukiyo-e Themes

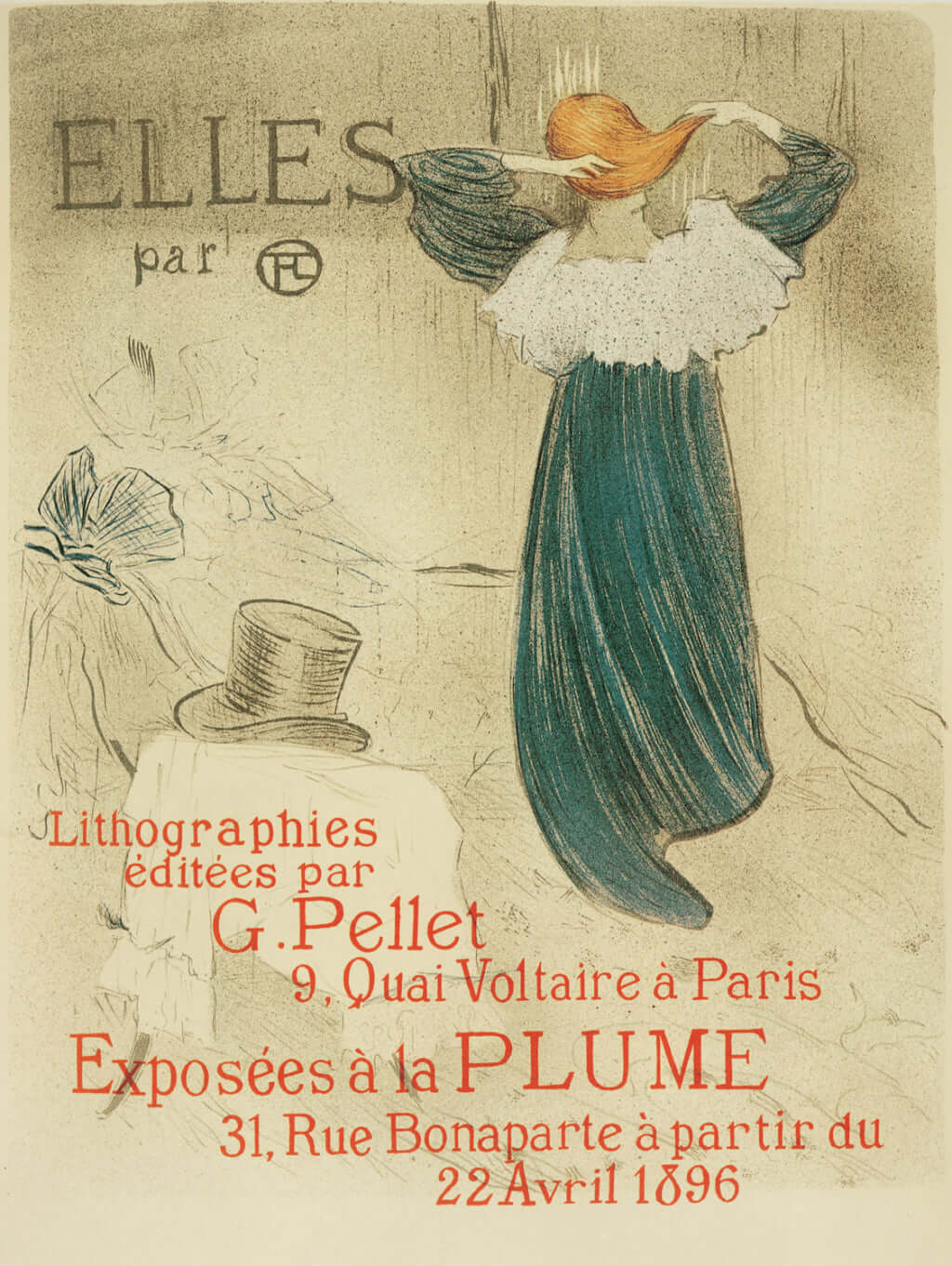

Japanese printmaking motifs are also recurrent in the work of Toulouse-Lautrec, either in his lithographies or his paintings. For example, the posture of the cat in the 1895 ‘May Belfort’ is reminiscent of those that feature in the work of Kuniyoshi Utagawa. While the powdered face and accentuated lips of ‘Elsa the Viennoise’ (1897) might not be a direct reference to Japanese beauty standards, ‘Woman in Bed, Profile, Getting Up’ from the 1896 Elles series instantly makes one think of the figures of ukiyo-e.

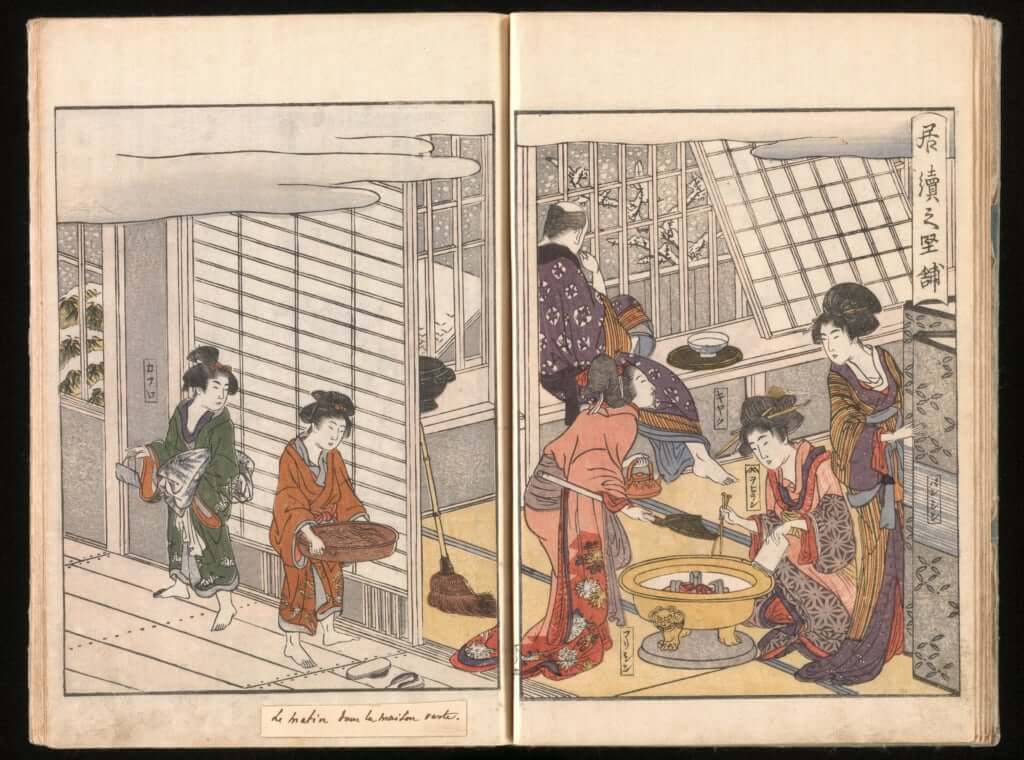

This series was equally inspired by the illustrations of Utamaro Kitagawa’s Yoshiwara seiro nenju gyoji (Picture Book of the Green Houses), a collection of stamps depicting the pleasure district of Yoshiwara in Tokyo in all its quotidian banality, without a hint of eroticism. This work of the great master is one of the last before his death in 1806 and arrived in France thanks to Edmond de Goncourt, who published it in the book Outamaro, le peintre des maisons vertes (Outamaro, painter of green houses) in 1891. The same year, an exhibition of Japanese prints took place at the School of Fine Arts in Paris, and was undoubtedly attended by Toulouse-Lautrec.

The series of 11 lithographies Elles depicts sex workers at various times throughout the day in banal everyday scenes, reworked through the eye of the artist. Not evocative enough to be fantasised about, the fin-de-siècle audience snubbed the series, largely out of step with the voyeurism of the time.

Popular with Japanese Audiences

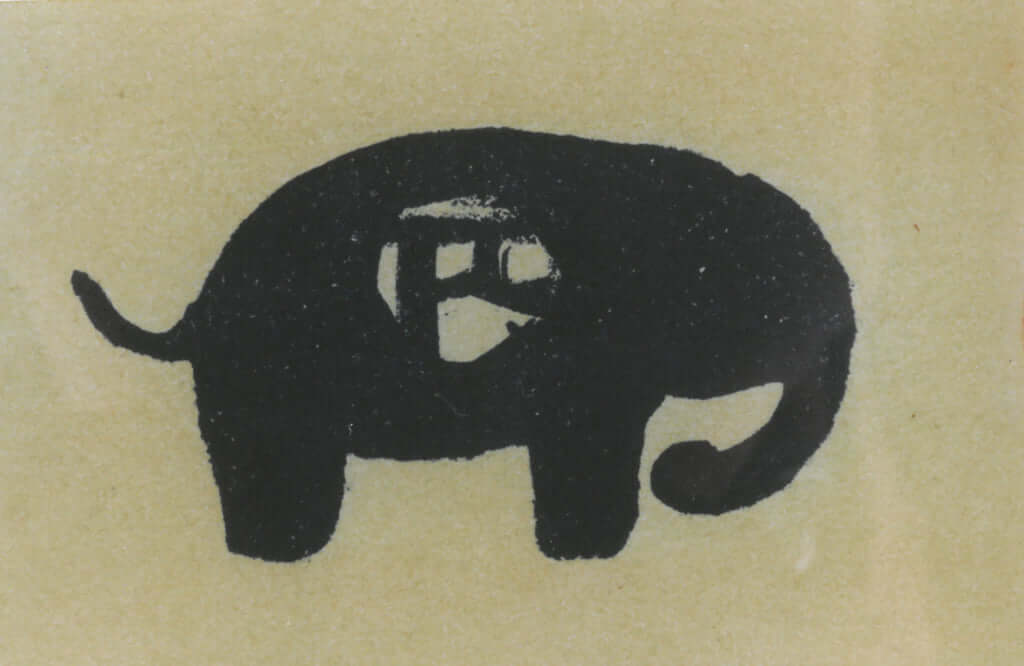

From his use of movement, to his representations of the triviality of the quotidien, as well as his signature of calligraphic initials in a circle, Toulouse-Lautrec admired, and was inspired, by Japanese art. He succeeded in capturing its essence and using it in his own work, and this is likely the reason why he is one of the most popular Western artists in Japan.

Of course, he was supremely capable of capturing a frivolous vision of a dream-like Paris. But maybe his work is also so popular because Japanese viewers are able to identify something familiar in the tender rendering of the small details of everyday life, an element so central to Japanese culture. His hometown of Albi is now a real hit with Japanese tourists, with even the Emperor paying a visit in 1994.

It is here in Albi that you’ll find the holy grail, the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, home to the leading public collection of his work. Following his death in 1901, his family offered the remaining work from his studio to a number of major Parisian museums, all of whom refused the collection. The then recently established museum in Albi accepted the work, paying homage to its most famous export. It is a chance for fans of the painter, from Japan or elsewhere, to get to know the full scope of his work, all in one location.

More information on the artist’s work can be found on the website for the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum in Albi.

Anonymous. ‘Toulouse-Lautrec posing as a cross-eyed Japanese man', 1892 © Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. ‘Doctor Tapié de Céleyran’ 1893-1894, oil on canvas, 108 x 50 cm Albi, Toulouse-Lautrec Museum © Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. ‘ELLES’, 1896 © Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France

『青楼繪本年中行事』 ‘Yoshiwara Picture Book of New Year’s Festivities (Seirō ehon nenjū gyōji)’ 1804. Kitagawa Utamaro Japanese. MET Museum

Toulouse-Lautrec's signature: a monogram in an elephant © Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi, France

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

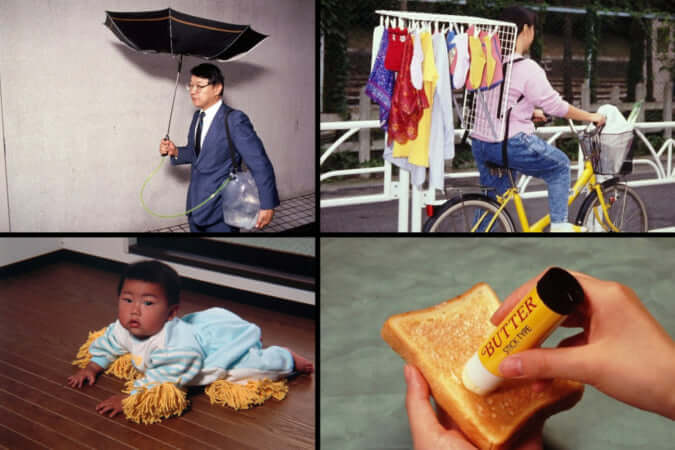

‘Chindogu’, the Genius of Unusable Objects

Ingenious but impractical inventions: this was all that was required for the concept to achieve a resounding success.

-

Tokihiro Sato, Shedding Light on an Invisible Presence

Photographers are generally behind the camera, but 'Photo Respiration' represents the artist's ephemeral appearance.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.