Tohl Narita, an Iconic ‘Tokusatsu’ Visual Artist

Artistic director and creator of cult characters like Ultraman, this artist shaped the history of special effects in Japanese cinema.

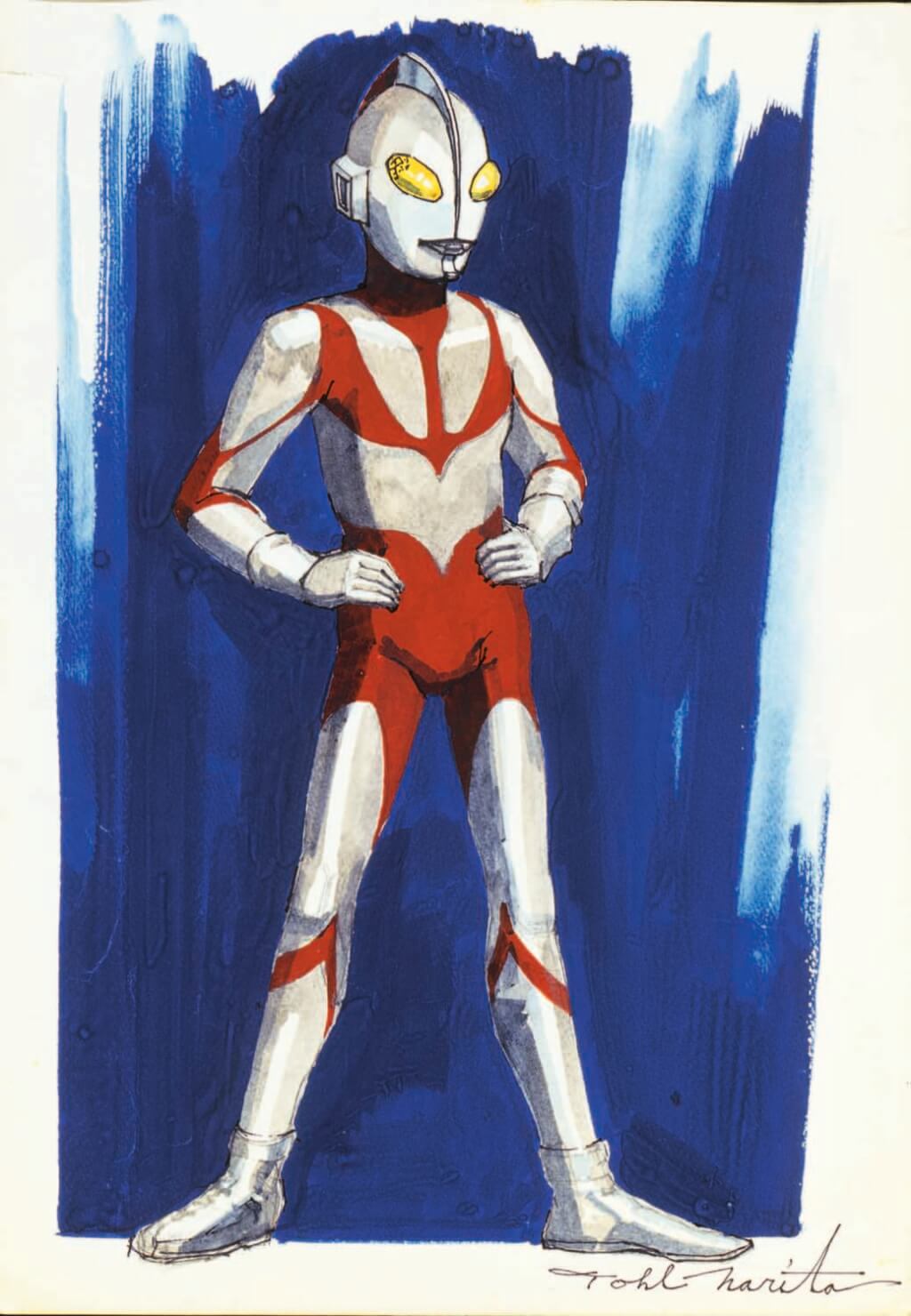

‘Human No.1, No.2’, Tohl Narita, 1972

One of the most important artists in the history of tokusatsu (video productions using special effects) was Tohl Narita, who was the creator of some of the genre’s iconic characters. Artist, sculptor, artistic director and author, he worked on various productions by Toho during the Showa era, and also on several television series by Tsuburaya Productions, like Ultra Q and Ultraman, which were very popular in Japan in the 1960s. Strongly influenced by the tradition of fine arts, his work stands at the crossroads between academic and popular culture.

Tohl Narita (1929-2002) was born in Kobe but grew up in Aomori prefecture, where his family moved in 1930. He burnt his left hand when grabbing some coal from the irori (traditional Japanese fireplace dug into the ground) in his home before he turned one year old, and despite undergoing various surgical procedures, his hand never healed completely. His injury meant he was only able to paint with his right hand, but this did not discourage him from becoming a painter. In 1950, he enrolled at Musashino Art University, where he studied foreign painting before specialising in sculpture.

A career in special effects, starting with Godzilla

After graduating, Tohl Narita was recommended by an acquaintance for a role in the production team for the film Godzilla, produced by Toho in 1954. He built a miniature building prop that was to be destroyed by the monster. This encouraged him to get more involved in film production design, and Tohl Narita decided to carve out a career in special effects while also continuing to work as a sculptor.

Later, he was promoted to special effects artistic director at Toei, then executive artistic director at Tsuburaya Productions. He worked on the special effects series Ultra Q (1966), Ultraman (1966), Ultraseven (1967) and Mighty Jack (1968), where he worked simultaneously to design the heroes, kaiju (monsters) and mechanisms. He then continued to create various characters and became a major figure in kaiju eiga (monster movies) and tokusatsu (contraction of tokushu satsuei, ‘special effects’ in English).

Varied sources of inspiration for designing kaiju

Tohl Narita’s approach to designing his monsters was somewhat surprising. He believed that abnormal beings could only be created in an abstract manner, with unusual proportions, and avoided the traditional approach of simply enlarging animals, insects and other things to create kaiju. To that end, he devised rules to be applied when designing his creatures, which have since gone down in history. Even though the artist never said as much in his lifetime, his creatures can also be seen to personify destructive natural forces like earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons that have regularly struck Japan for centuries.

Tohl Narita often drew inspiration from creatures found in the real world when creating his work, incorporating more conceptual elements that evoke surrealism, primitivism and dadaism; these can notably be seen in the illustrations of monsters from the series Ultraman. Moreover, one of his kaiju, the evil alien Dada (who appears in Ultraman) seems to take his name from the aforementioned European artistic movement. There are many and varied examples, as the artist had multiple sources of inspiration. For one of his favourite designs, the kaiju Kemur from the series Ultra Q, Tohl Narita is thought to have been influenced by Egyptian hieroglyphics that give Kemur a highly distinctive asymmetric face that is very popular with those who watch the series.

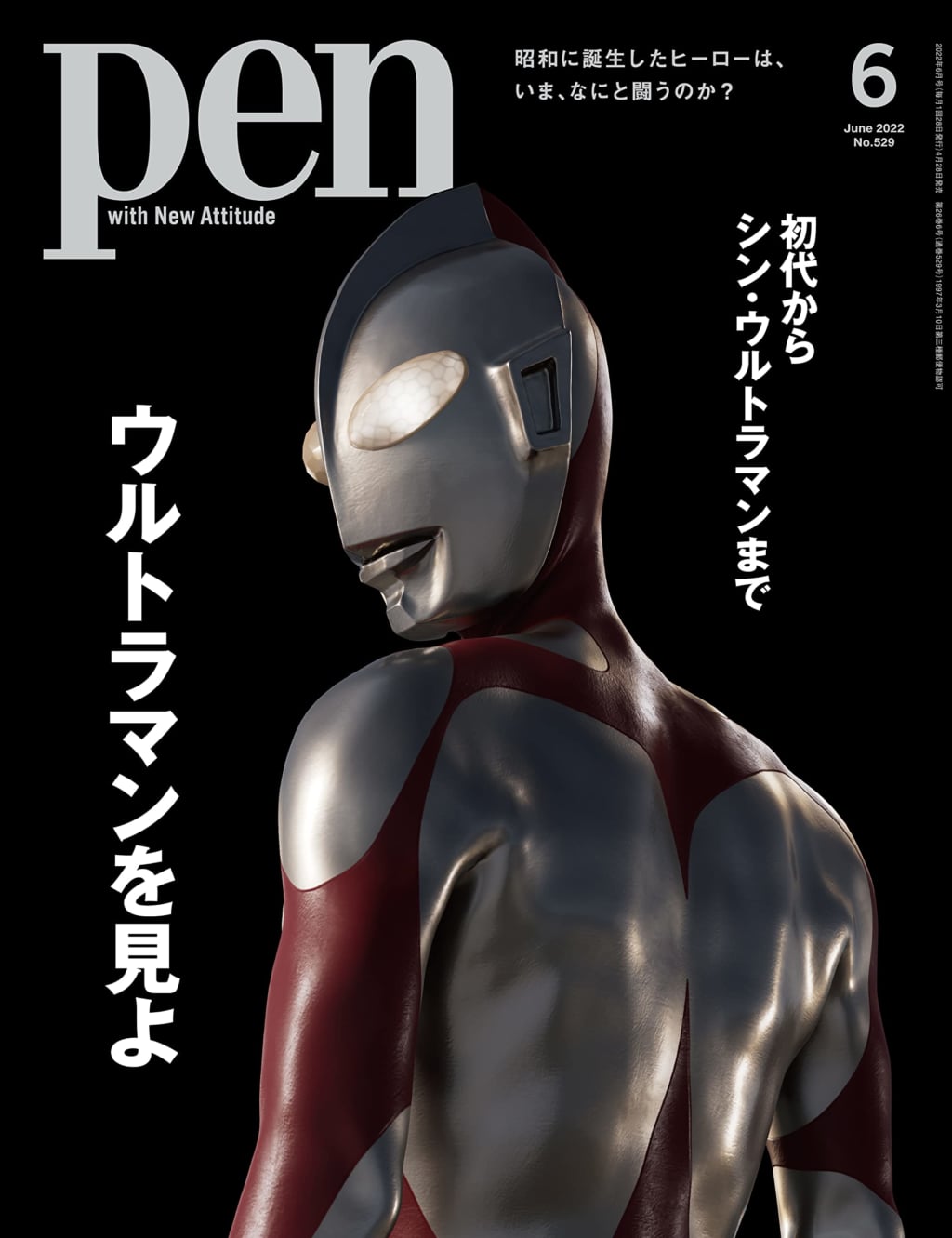

Since his death in 2002, Tohl Narita’s art has continued to inspire modern work in all domains. His influence can be seen particularly in the work of visual artist Takashi Murakami, founder of the Superflat movement and one of the most famous figures in contemporary art, who declares that Tohl Narita is one of the artists who influenced him most, due to the highly artistic quality of his work from the very beginning of his career. The directors of Shin Godzilla (2016), Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, were also inspired by Tohl Narita’s concept in reinventing the cult character from the 1966 television series 1966, Ultraman, in the film Shin Ultraman scheduled for release in 2022.

Tohl Narita’s work can be viewed on his official website.

成田亨作品集 (Anthology of the Work of Tohl Narita) (2014), a book published by Hatori Press, Inc.

The pieces presented here are taken from the book 成田亨作品集 (Anthology of the Work of Tohl Narita), Hatori Press, Inc., 2014. Courtesy of Hatori Press, Inc.©︎ Eternal Universe ©︎ Narita/TPC ©︎ TOHO ©︎ NTV

‘Alien Baltan, Final Version’, Tohl Narita, 1966

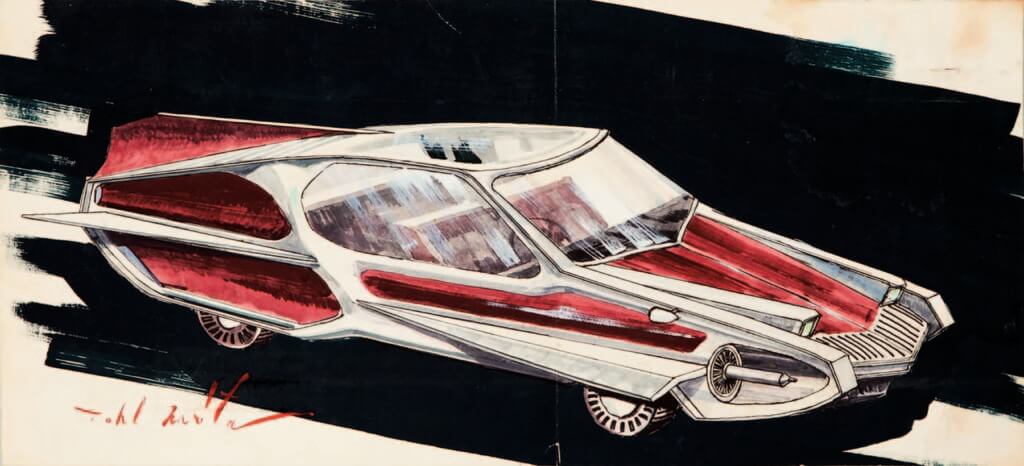

‘Pointer’, Tohl Narita, 1967

‘The Devil High Priest of Kurama’, Tohl Narita, 1987

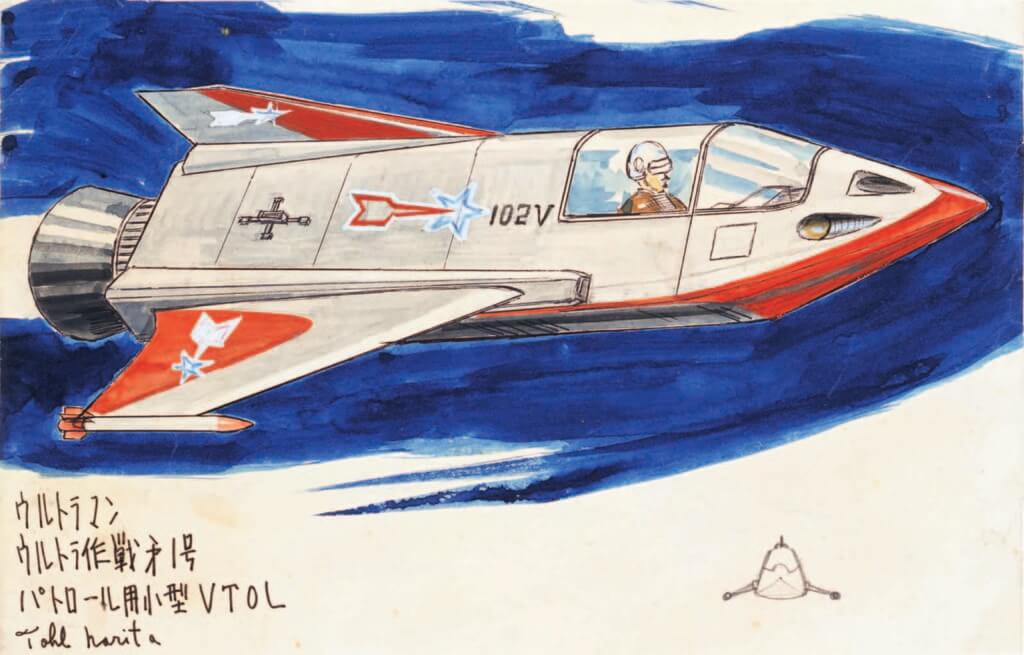

‘Beetle No.2, Prototype’, Tohl Narita, 1966

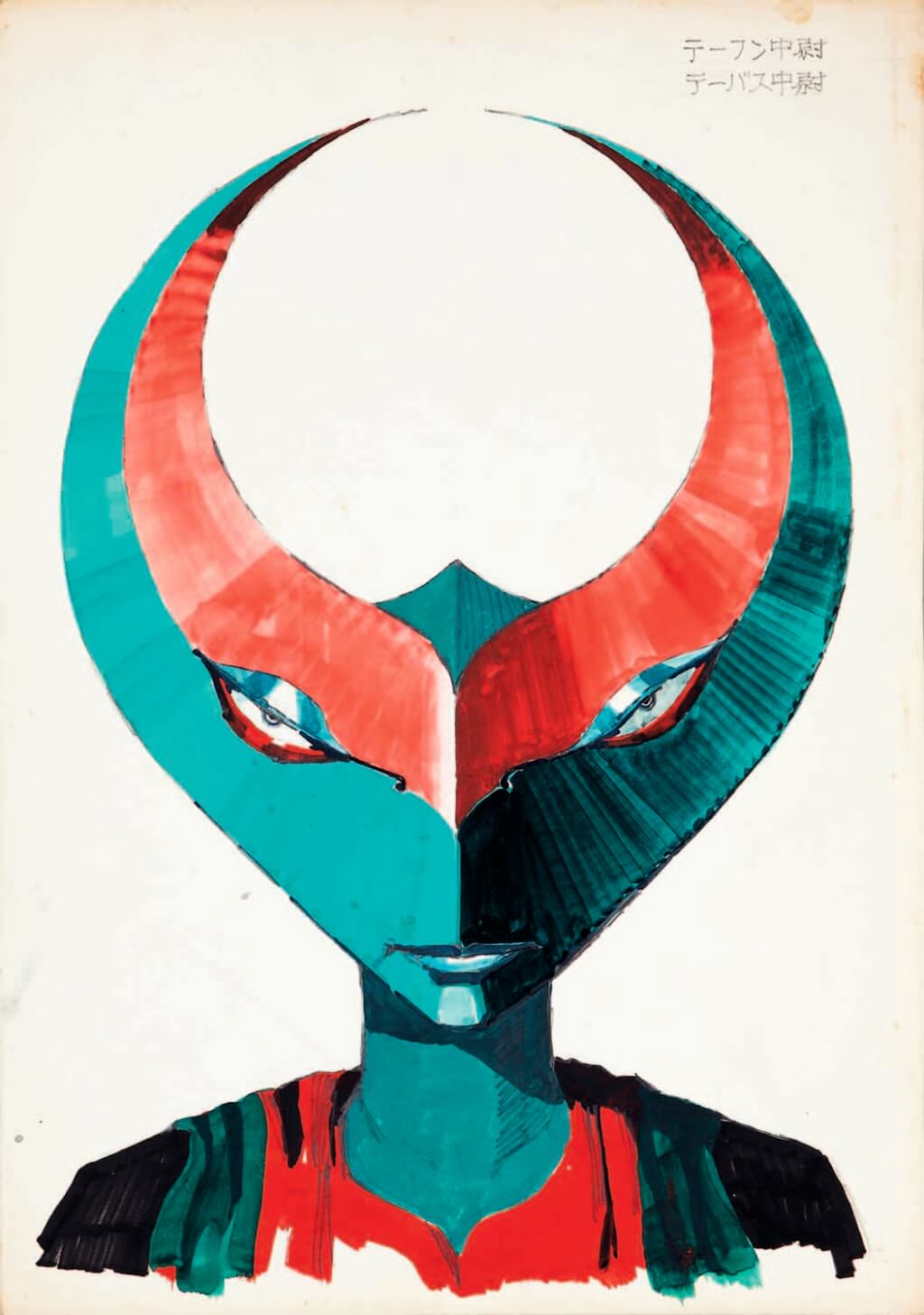

‘Lieutenant Teibasu’, Tohl Narita, 1976

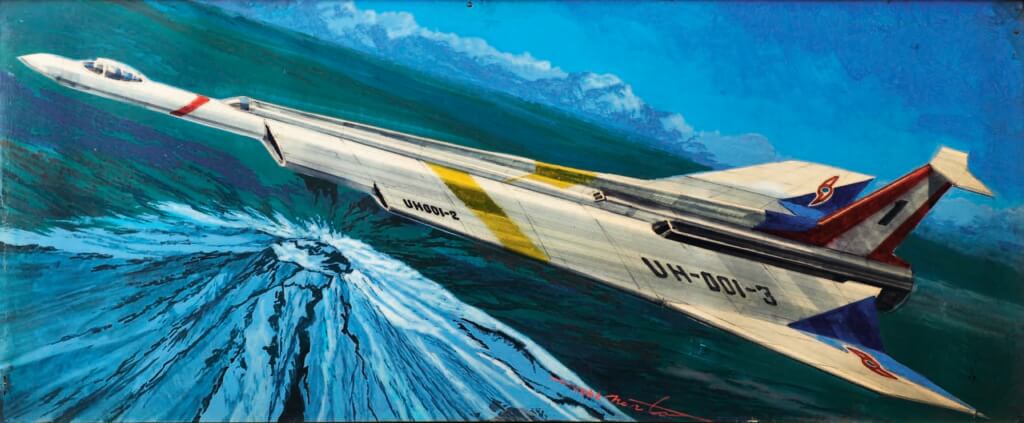

‘Ultra Hawk No.1’, Tohl Narita, 1980s

‘Ultraman’, Tohl Narita, 1966

Pen Magazine (ペン), June 2022 issue dedicated to Ultraman and the film ‘Shin Ultraman’. © CCC Media House Co., Ltd.

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.