Underground Noise Music Questions the Frameworks of Art

An exhibition on Japanese art in the 1980s/1990s foregrounds an entire genre of music as a radical disturbance.

EYE - ‘Sleeve art for Super roots 9’ (2006). Courtesy of Boredoms.jp.

Where one may expect the contemplative silence of a white cube, noise permeated Los Angeles’s Blum & Poe in the course of Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s.

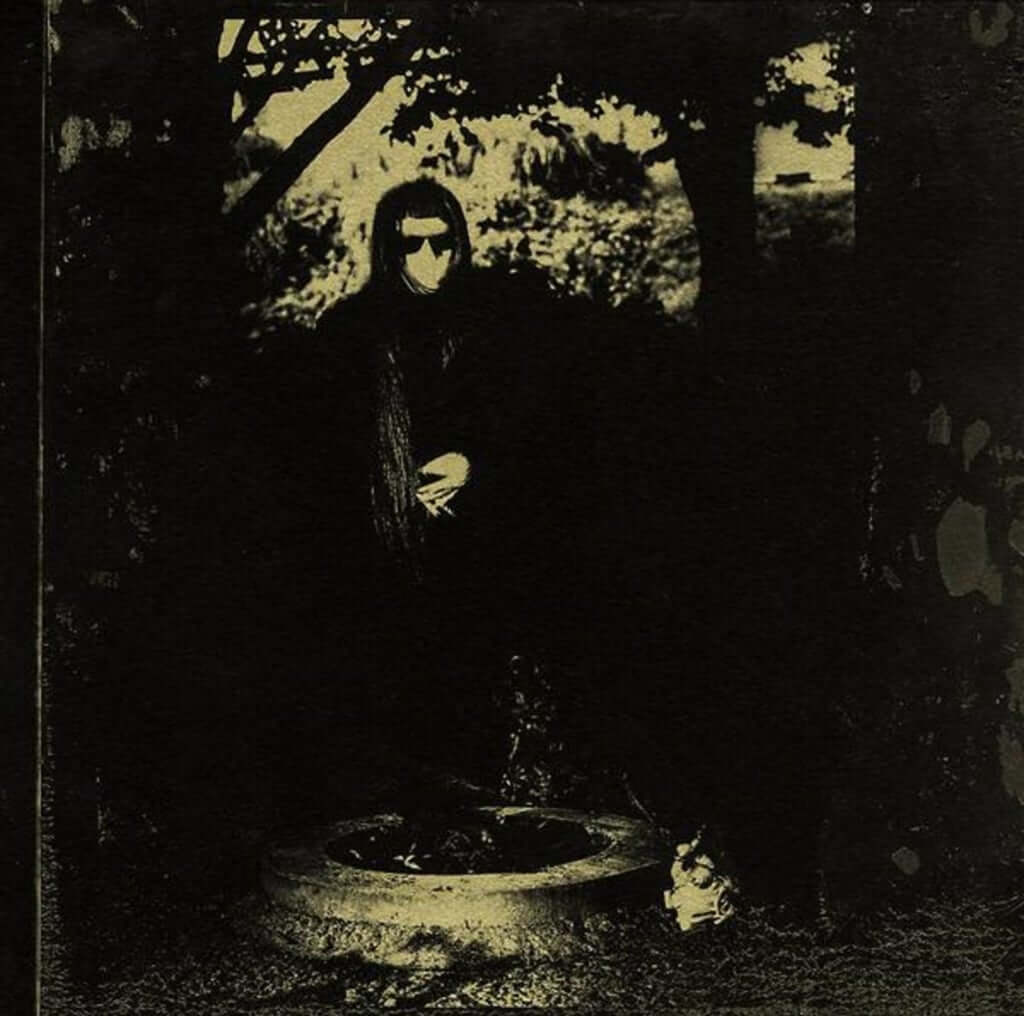

Running from February to May 2019, the gallery honoured ties to Tokyo with twenty-five visual artists coming out of an explosive wave of culture in Japan. But next to works by Tadanori Yokoo or Mariko Mori, the dark shamans and enfant-terribles of Japanese music also made appearances. Keiji Haino, an Artaud-like enigma of the sonic avant-garde, seemed to warp time itself through improvised vocals and dark guitar twangs. Experimental noise-pop artist EYE—once infamously seen on a bulldozer destroying a venue he was performing in—had his arms strapped with wires as his movements immersed a crowd in feedback.

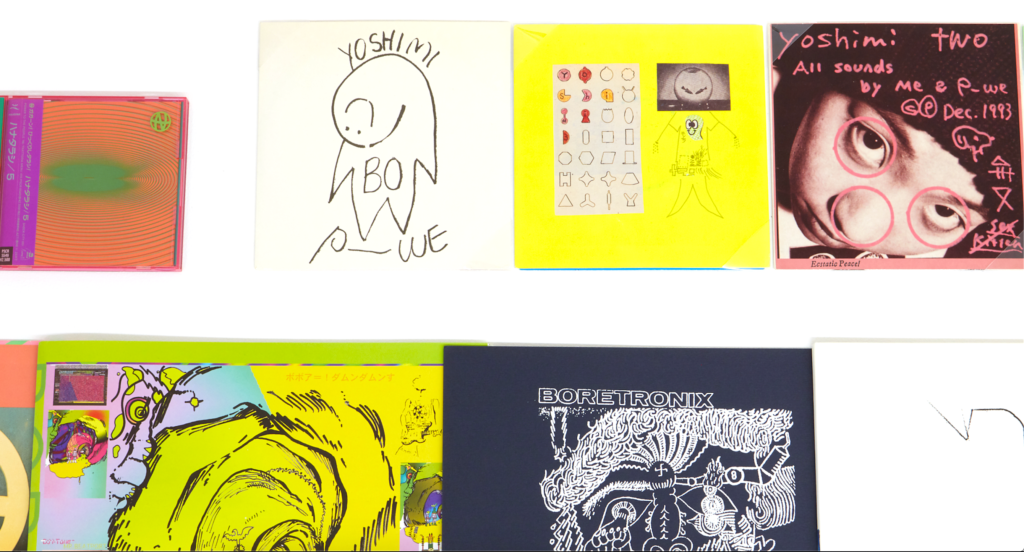

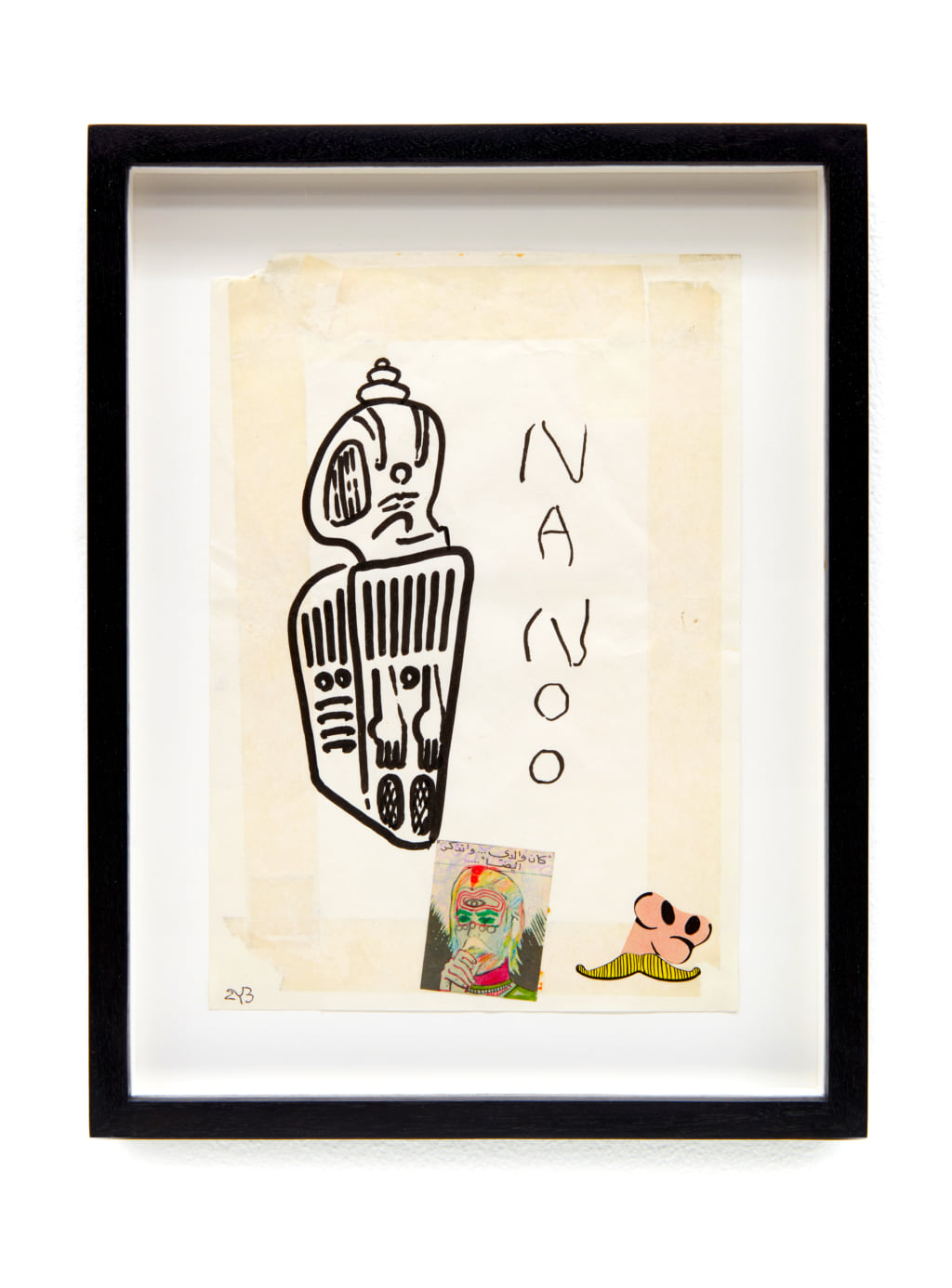

In the underbelly of Japan’s post-war legacy, the abrasive techniques of noise music represented a nihilistic side to heteronormative pop culture, with its distorted feedback loops hosting an entire underground society. Parergon displays rare records and other ephemera retrieved from an analog past, alongside visual art made by some of its musicians. Next to known figures in contemporary art, the entire scene is immortalised in an extensive publication with contributions by music scholar David Novak and Peter Kolovos of the Black Editions label.

Subterranean Resonances

Blum & Poe in Los Angeles, New York, and Tokyo has a history of representing the most prestigious names in Japanese Fine Art, including Yoshitomo Nara, Takashi Murakami, and Lee Ufan of Mono-ha. In Parergon, curator Mika Yoshitake strings together diverse practices—sculpture, painting, photography, and performance—of a particularly productive era in Japanese history, tracing new conceptual languages between minimalist or neo-pop tendencies. The exhibition refers to Jacques Derrida’s 1979 essay that questioned the ‘frameworks’ of art, a moment when Western philosophy noticed a shift in traditional cultural demarcations. But looking at Japan, it appeared that it had already embodied a collapse of categories under its advanced capitalism that blends high art and mass culture or East and West indiscriminately, and Parergon then re-evaluates post-war Japan’s unique position within postmodern discourse.

In attempting to ‘reframe’ Japanese art, Parergon includes an entire subterranean community of music as a cultural artefact in itself. The exhibition presented coveted physical material that had then circulated, but what was really on display were the resonances that carried them. Noise’s submerged circumstances, as an uncharted space of eccentric individuals with recordings notoriously hard to find, actually manifested an underground network before the arrival of the Internet. As international audiences sought out its revolutionary sound, the technological phenomena of feedback seemed to emphasize invisible links stretching from Japan to the West.

For the global art world which often sidelines sonic practices, the Japanese noise scene had a unique significance. Rather than forgrounding commercial objects on pedestals, noise music’s fleeting performances forged an interconnectedness. And rather than relying on essentialist discourse, it had already escaped all boundaries the moment it had crystallized.

Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s (2020) is edited by Mika Yoshitake and published by Blum & Poe and Skira Editore.

Further information about EYE and Boredoms can be found on a dedicated website and information on Keiji Haino and other musicians from the Black Editions archive can be found on the group’s website.

Images courtesy of Boredoms.jp andBlum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Hanatarash's Live Album CDs, Ephemera from Black Editions Archives. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

EYE, ‘Sleeve Art for Lift Boys’ (2012). Courtesy of Boredoms.jp. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

Album cover of Keiji Haino's ‘Watashi Dake?’ (1981). Courtesy of Black Editions Archive.

Ephemera from Black Editions Archives. Includes works by Hanatarash, Boredoms,Yoshimi P-We and more. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

EYE, ‘Facial Index’. Courtesy of Boredoms.jp. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

Ephemera from Black Editions Archives. Includes works by Merzbow, Hijokaidan and more. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

EYE, ‘Ongaloo’ (2005). Courtesy of Boredoms.jp.

Ephemera from Black Editions Archives. Includes works by EYE, Boredoms and others. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

EYE, ‘NANOO’ (1996). Courtesy of Boredoms.jp. Photo: Heather Rasmussen

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.