Yurie Nagashima, a Leading Female Voice in Japanese Photography

Tank Girl. 1994, C-print

Photographer and writer Yurie Nagashima grew up surrounded by strong female role models: her teachers, members of her family, and Simone de Beauvoir. Women that had nothing to do with the notion of how a woman should be or behave in the Japan of the 90s. Ignoring those instructing her to be more feminine, the young Nagashima decided to raise her own unique voice through photography. And her voice was heard. Still a university student, Nagashima won the Urbanart award. Serving as a member of the jury was none other than the highly-acclaimed and polemic photographer, Araki Nobuyoshi.

The Personal is Political

From the series Family. 1997, C-print

The series of photographs that won her the award depicted Nagashima’s family in the nude, and quickly became a national sensation. Soon after, the term ‘onnanoko shashin’ (or Girls’ photography), was born. It referred to a group of female photographers, with Nagashima as one of the lead figures, who were documenting their day-to-day lives and expressing themselves for the first time freely and in the open. Self-portraits and nudity were common and that would frequently draw criticism over the real motivations of these photographers.

Onion. 2005, C-print

When asked about the series, Nagashima explains that it was not meant to be about her family, but a family, any family. The artist wanted to start a dialogue about the concept of family itself as the smallest political unit. The family as a reflection of the dynamics that move our society. This quest to explain in images the concept of family, which started with her in the role of daughter and sister, has naturally evolved over time as she has adopted new roles —mother, wife and daughter-in-law.

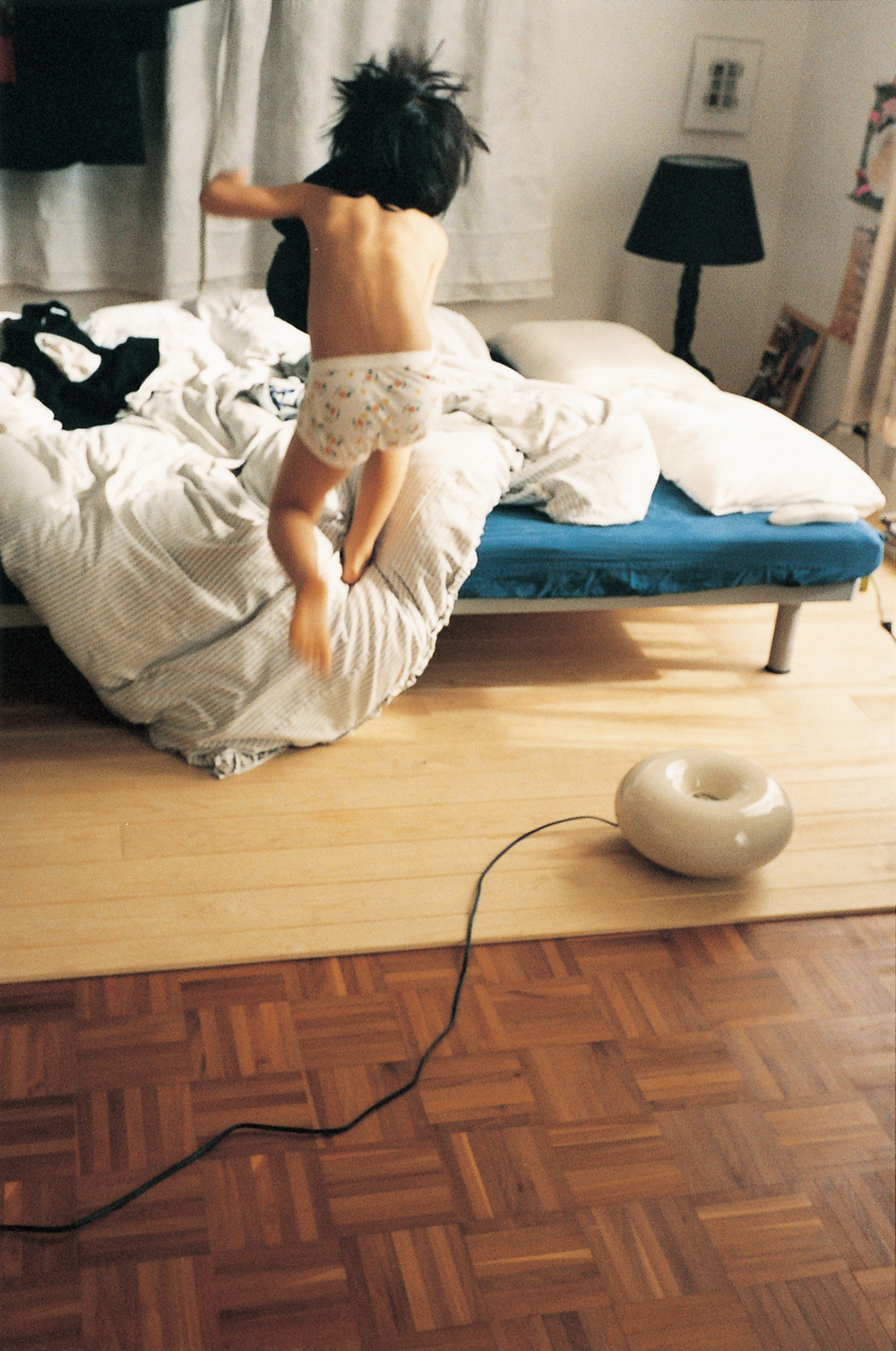

From the series 5 comes after 6. 1997, C-print

The attitude of the artist towards the act of photography itself has also changed. Less bold than before, she now accepts that there are moments that she needs to let pass by without the sound of the shutter. But even though the tone of her voice has changed as she has grown up and deepened her knowledge of feminism through her studies in Sociology, the message is still clear. For one of her latest installations, the artist sewed with her mother a tent made up of her family’s old clothes, further shedding light on the concepts of family and home that have always been at the core of her work.

From the series about home. 2016. Embroidery, T-shirts, Cotton bags, ect., Dimensions variable

From the series 5 comes after 6. 1997, C-print

From the series 5 comes after 6. 1997, C-print

from "5 comes after 6" (2014)

The Kiss (From the series 5 comes after 6). 2011/2017, C-print

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

Tokihiro Sato, Shedding Light on an Invisible Presence

Photographers are generally behind the camera, but 'Photo Respiration' represents the artist's ephemeral appearance.

-

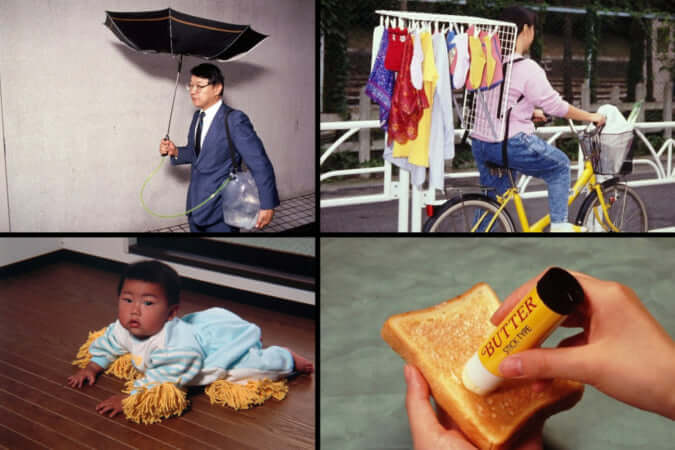

‘Chindogu’, the Genius of Unusable Objects

Ingenious but impractical inventions: this was all that was required for the concept to achieve a resounding success.