Charlotte Perriand and Japan

During a four-month trip in 1940, the French architect immersed herself in the subtleties of life on a tatami mat and of Japanese minimalism.

© AChP

On 15 June 1940, Charlotte Perriand boarded the Hakusan Maru to embark on a journey to Japan that would take two months and six days. The architect, aged 36 at the time, left France a few days before the German army arrived in the country and headed to Japan, having receiving a proposition from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. She had notably worked in Le Corbusier’s studio, and was called upon to advise on the production of industrial art in Japan. ‘At the time, Japan was like the Moon’, she explained before her big departure, and indeed it would feel like she had arrived on another planet.

While wandering through cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka and exploring the nooks and crannies of the Japanese countryside to select ‘objects worthy of being exported’ for the ministry, Charlotte Perriand discovered not only the art of living in Japan, but also the art of inhabiting. ‘In Japan, which was 100% traditional at the time, I discovered emptiness, the power of emptiness, the religion of emptiness, fundamentally, which is not nothingness. For them, it represents the possibility of moving. Emptiness contains everything’, she explained to France Culture in Mémoires du siècle in 1997.

Two exhibitions in Japan

During her travels, the architect presented conferences at schools, production centres and cultural institutes, accompanied by her translator Mrs Mikami and her assistant Sori Yanagi. Over the four months, whenever speaking to people, Charlotte Perriand made sure to emphasise the thing she considered indispensable: innovation. ‘My aim was to give a sense of creation back to these artisans who were so focused on their traditions or trapped in reproducing inanimate objects copied from publications (…) I encouraged all of them to create new objects’, the architect explained in her autobiography, A Life of Creation.

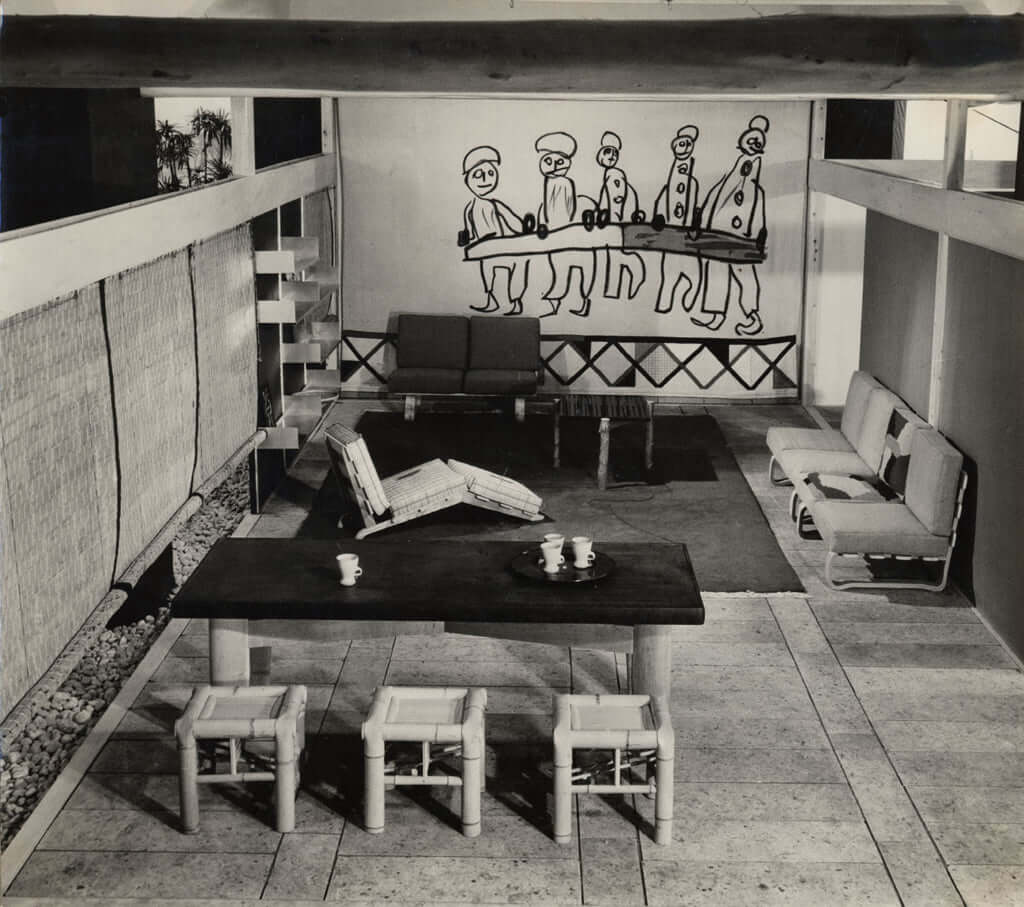

This gave her the idea to stage an exhibition entitled Selection, Tradition, Creation in 1941, which would synthesise her mission: to bring together all the necessary elements of equipment for the home, combining modern spirit and Japanese tradition for European use. It included a low table with standard wooden legs and a black lacquer tabletop, which was much higher than Japanese low tables, and a chaise longue, resolutely modern but made from bamboo and wood.

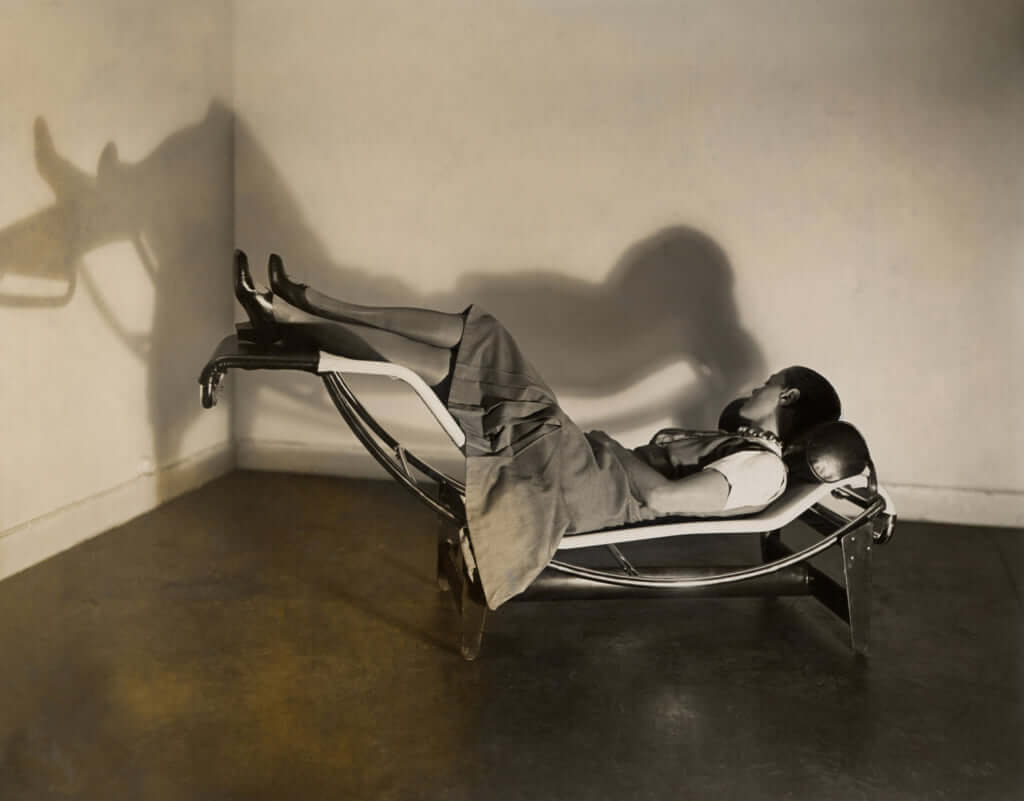

Iconic pieces recreated using local materials

‘The various institutes will have to gather objects made in their region and select those that are to be exported. To fill the gaps, new models will be created by the best artisans’, states Jacques Barsac in the book Charlotte Perriand et le Japon. Charlotte Perriand returned to her own creations for the occasion, a set of chairs and tables designed in the 1920s and 1930s, and adapted them using materials available in abundance in Japan: bamboo and wood. ‘I saw some sugar tongs made from bamboo, created by the Institute of Tokyo, and it gave me the idea to transpose the stainless steel chaise longue from 1928, using the flexibility of machined bamboo instead of steel’, she wrote in A Life of Creation.

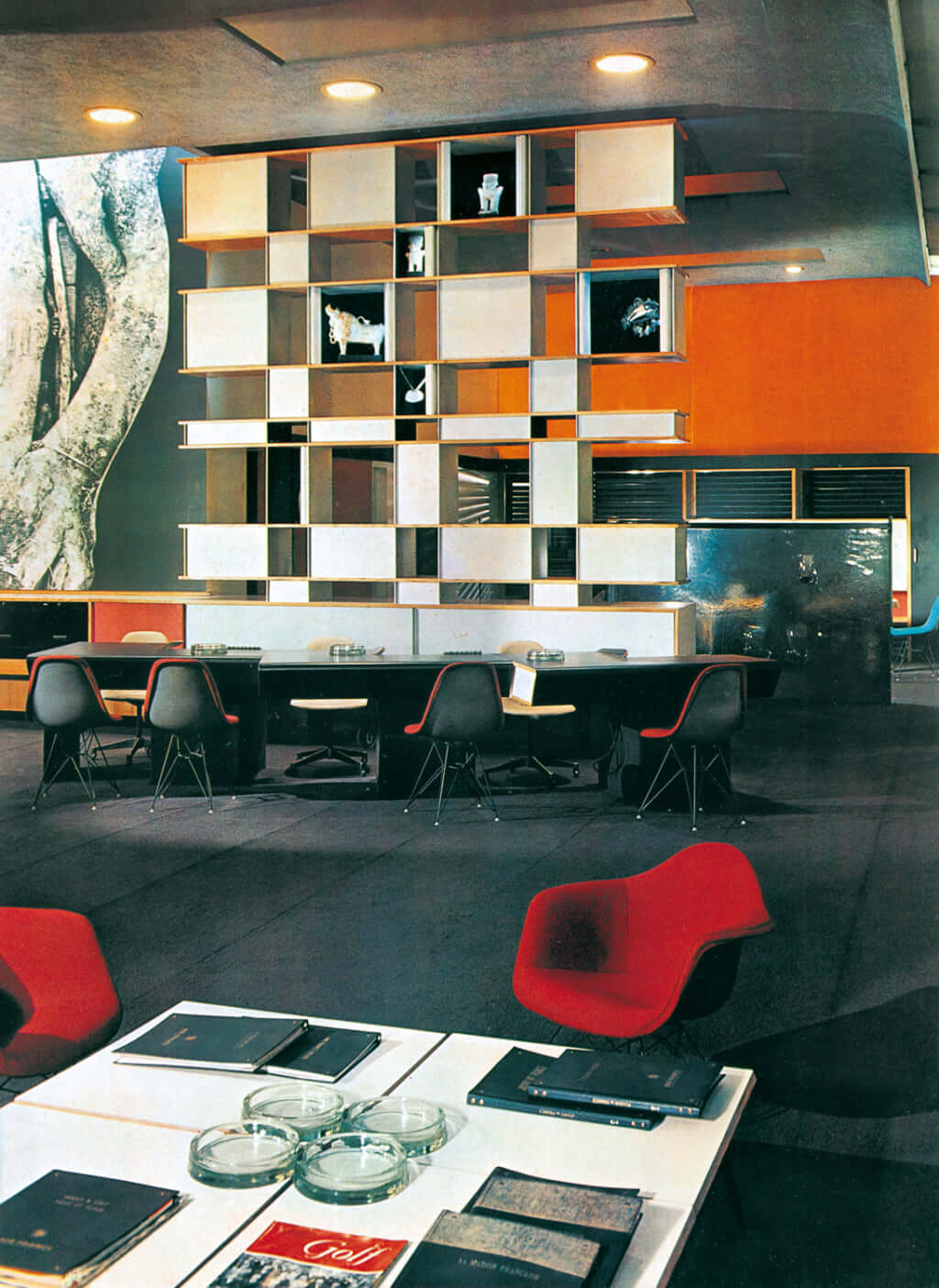

Charlotte Perriand left Japan in winter 1942 to head to Indochina before going back to France. But the architect’s Japanese adventure didn’t stop there. She returned to Tokyo in 1953 when she remodelled Air France’s offices, before staging a new exhibition, Synthesis of the Arts, in 1955. This time, she called upon her associates of the time, Fernand Léger and Le Corbusier, who created ceramics and a tapestry respectively. These creations adorned the exhibition where, in the middle of the stone floor and luxurious vegetation set up for the occasion, one of the designer’s most iconic pieces was unveiled: her Nuage (‘cloud’) bookshelf.

‘The Tea House’, her final Japanese creation

The links between Charlotte Perriand and Japan did not weaken over the years. After designing an apartment for Jacques Martin, CEO of Air France in Tokyo, she worked on the Japanese ambassador’s residence in Paris and the Shiki Fabric House showroom, as well as the apartment belonging to its founder Tadao Matsui. The architect’s career in Japan drew to a close in 1993, with the creation of a tea house in Tokyo at the request of her friend and ikebana master Hiroshi Teshigahara, for the UNESCO Japanese Cultural Festival. She returned to The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura, which she had first discovered in 1930. ‘The tea house does not claim to be anything other than a simple, rustic house’, the book states. ‘It is just an ephemeral construction, built to serve as a sanctuary for a poetic impetus.’

Charlotte Perriand, then aged 90, surrounded her tea house with a bamboo forest to shelter it from the noise from the capital. Its pine structure, furnished with four and a half tatami mats and covered by a canvas cone suspended from arches, which adds an ethereal touch, seems to be floating above black pebbles and little cups made from bamboo and filled with water.

In 2019, to mark twenty years since her death, the Fondation Louis Vuitton dedicated a retrospective to her, giving visitors the opportunity to view her creations and admire her famous tea house.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World (2019), a book on the architect’s work published by Gallimard on the occasion of the retrospective held by the Louis Vuitton Foundation in her honour.

© AChP

© AChP

© AChP

© Fondation Louis Vuitton

© AChP

© AChP

© AChP

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.