‘Garo’, An Era of Underground Manga

A niche monthly anthology running from 1964 excited arts scenes as the leading showcase for dark, experimental manga.

‘Garo’, Seirindo Kogeisha.

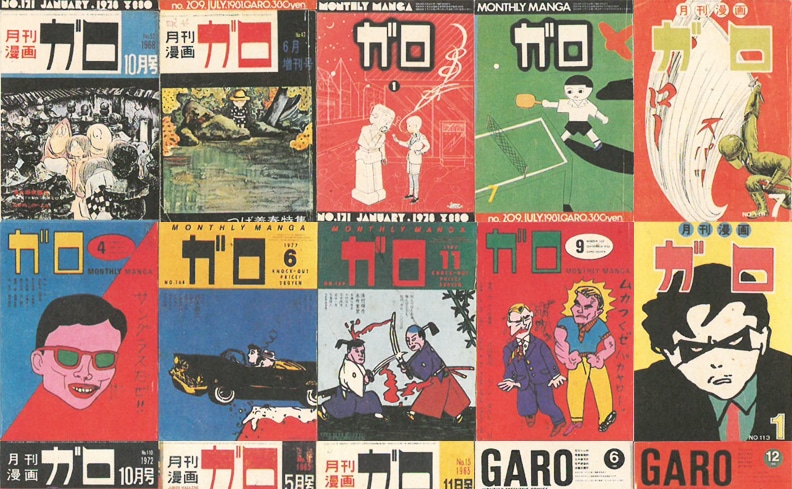

Having now been out of print for a couple of decades, one would be immediately confronted with a distinct presence coming across a rare edition of Garo. Each cover hosts artwork by manga history’s most distinguished names, in shockingly diverse art styles that impacted students, activists, and artists from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

As Japan’s most notorious alternative manga anthology, Garo’s pioneering artists ventured unhesitatingly into difficult subject matter—complicated historical dramas, existentialist takes on modern life, abstract illustrations, cruel depictions of poverty, and often, artistic inquiries into the erotique and grotesque. Though never deemed a successful ‘major’ magazine, Garo’s unboundedness sowed the seeds of contemporary manga—and for that, of all Japanese pop culture.

Graphical Insurgence

Garo‘s beginnings took place within a bygone era of Japanese culture, when manga only circulated through a kashi-hon book rental system, and all amidst a politically turbulent climate with frequent student protests. When first founded by Katsuichi Nagai in 1964, Garo featured the work of Sampei Shirato, an artist and essayist known for introducing gekiga—a gritty style of comics aimed towards adults that dominated manga in the 1960s and 1970s.

With Sampei Shirato’s politically conscious ninja-drama Kamui-den especially hitting a young left-wing audience, the serialised distribution of manga meanwhile established Garo as a revolution. The publication then came to be the first to recruit iconic gekiga artists, with the likes of Yoshiharu Tsuge, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, and even Shigeru Mizuki making contributions before achieving widespread fame.

An Unruly Enterprise

Garo was born amidst social turbulence, seemingly feeding from the strange energies of the time—the hangover and amnesia of World War II, Yukio Mishima’s public suicide, and the Yodogo hijacking incident—but its surreal expressions, combined with a dark sense of humour, guided a generational venture in the march towards the unknown.

Despite being part of a demanding industry sensitive to public opinion, the editors of Garo allowed absolutely anything to be published, however ominous in tone or critical of the status quo. When financial situations were dire and its aesthetics became impoverished, readers only focused in closer on the unpredictable characteristics. The experimental illustrations of those such as Suehiro Maruo, Seeichi Hayashi, or King Terry are now hailed for their phenomenal influence on graphic design. Rivalries emerged with other magazines who popped up to echo Garo’s model. Many were often more commercially successful, but they always followed in Garo’s footsteps.

By the 1990s, Garo’s popularity had started to decline. Six years after the death of Katsuichi Nagai in 1996, authors went their own ways, founding other anthologies like Ax. Though no longer in print, Garo is unanimously hailed as the hidden pillar of Japan’s manga industry—its atmosphere still creeps out of frames.

Garo has been out of print since 1992, but the works of many of its artists have been published and translated for international audiences. Collections of stories in its successor—Ax—have been published by Top Shelf Comics.

Cover of ‘Garo’ from 1993, with artwork by Suehiro Maruo.

Cover of ‘Garo’ from 1966, with artwork by Yoshiharu Tsuge. The edition particularly featured his works and published his legendary short, ‘Numa’ (Swamp).

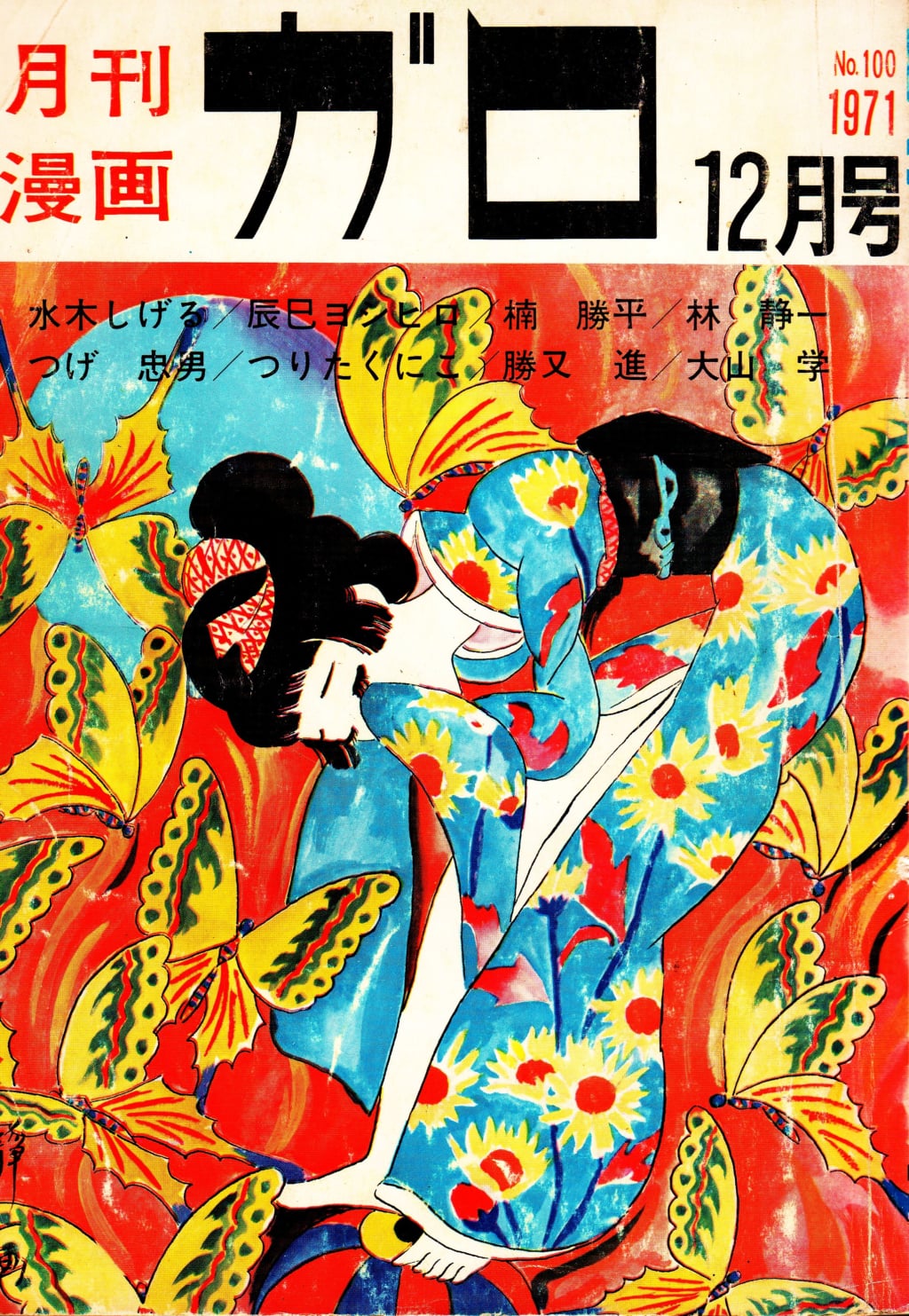

Cover of ‘Garo’ from 1971, with artwork by Seeichi Hayashi.

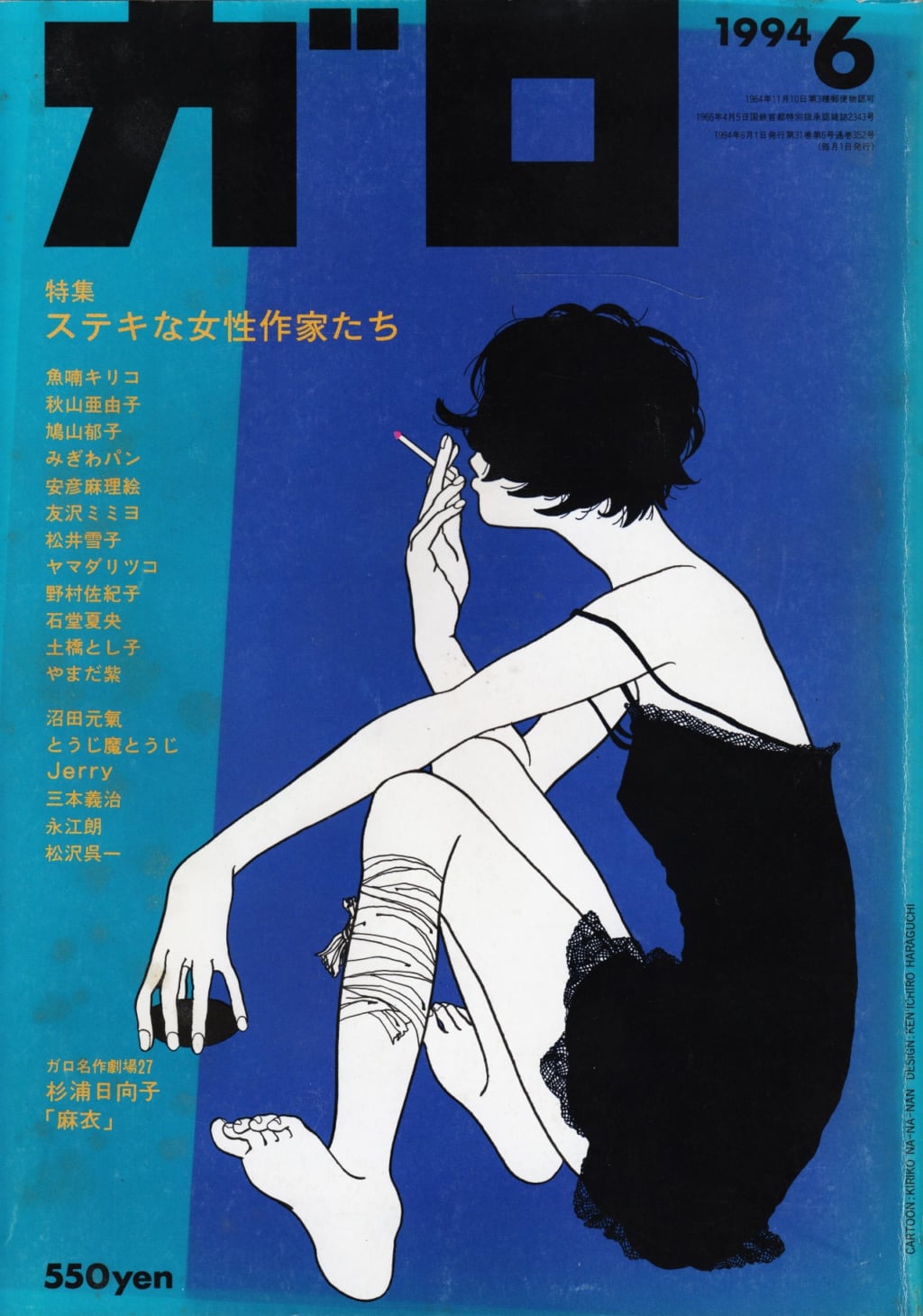

Cover of ‘Garo’ from 1994, with artwork by Kiriko Nananan.

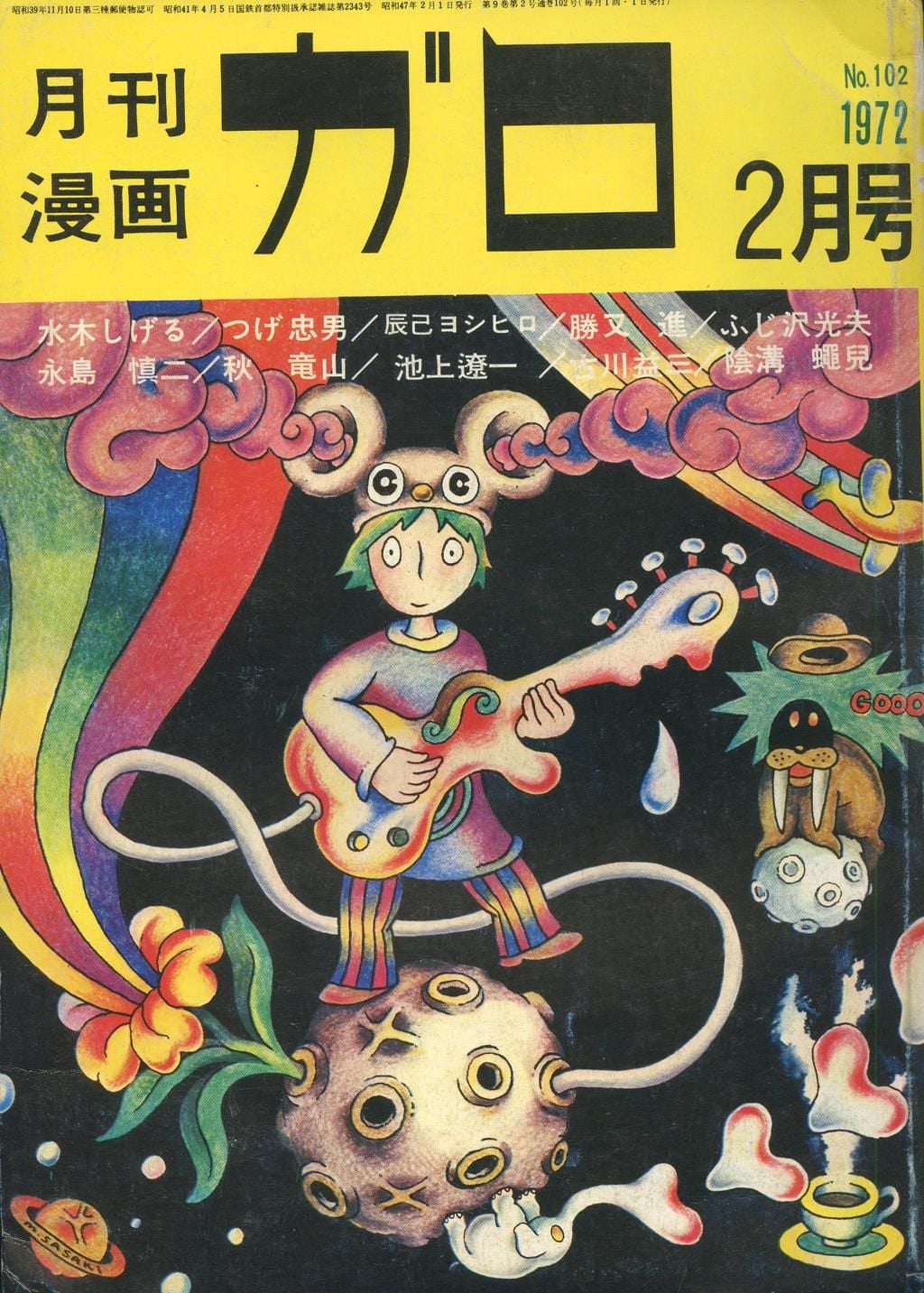

Cover of ‘Garo’ from 1972, with artwork by Maki Sasaki.

TRENDING

-

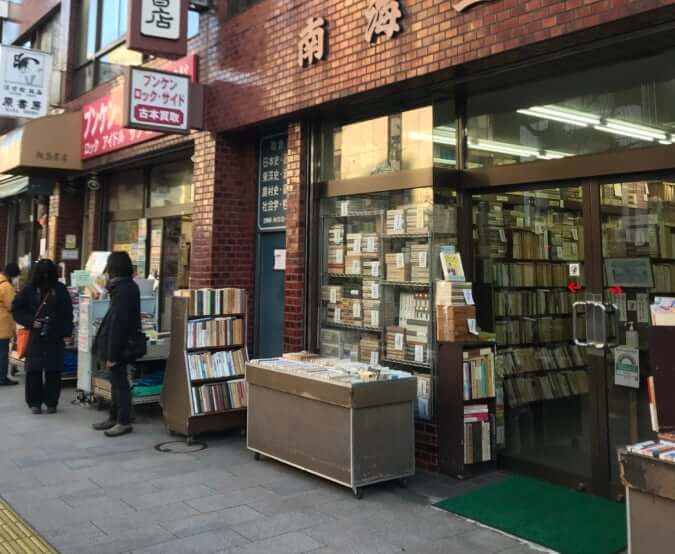

Jinbocho, Tokyo’s Book District

This neighbourhood in Chiyoda-ku has become a popular centre for second-hand book stores, publishing houses and antique curiosities.

-

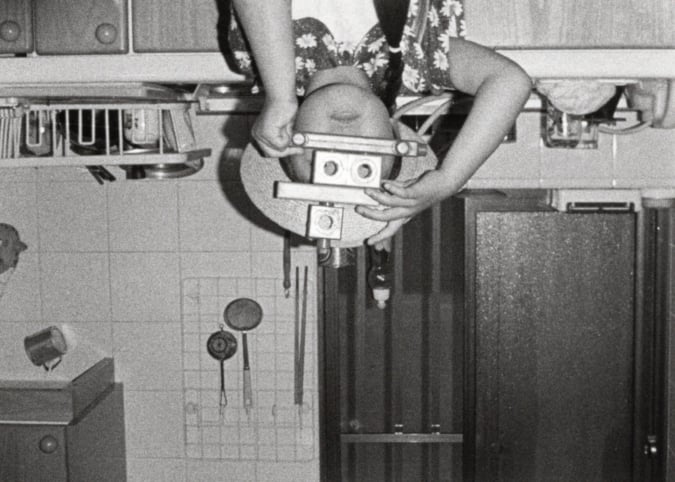

Issei Suda’s ‘Family Diary’, A Distant Look at Daily Life

For two years, he photographed his family using a Minox, a tiny camera notably employed by intelligence agencies.

-

‘Shojo Tsubaki’, A Freakshow

Underground manga artist Suehiro Maruo’s infamous masterpiece canonised a historical fascination towards the erotic-grotesque genre.

-

Recipe for ‘Okayu’ from the Film ‘Princess Mononoke’

This rice soup seasoned with miso is served by a monk to Ashitaka, one of the heroes in Hayao Miyazaki's film.

-

‘Kokoro’, Harmony Between the Heart and Mind

Meaning ‘heart’, ‘mind’ and ‘essence’ alternately, this Japanese term bears a philosophical dimension unique to the country.