Hayao Miyazaki, the Man Who Adored Women

The renowned director places strong female characters at the heart of his work, characters who defy the clichés rife in animated films.

San in ‘Princess Mononoke’ © Studio Ghibli

In 1984’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Hayao Miyazaki depicts a woman (who lends her name to the title of the film) whose traits are more often attributed to male characters: she is strong, independent, combative, virile. In his subsequent films, the filmmaker plays with stereotypes and brings to life women who buck the trend of animated film clichés. They are warriors, ordinary people, young, old, mothers, daughters, but above all believable and incredibly endearing.

Hayao Miyazaki is one of the most important 20th-century filmmakers. Born in Tokyo on 5 January 1941, he cofounded Studio Ghibli in 1985 with his fellow director Isao Takahata. A prolific filmmaker, he is considered a national treasure in Japan due to his popularity and the record box office success of his numerous films. He is a humanist director whose favourite themes are ecology, nature, technology, war, and humanity. The protagonists in his films are often women of all ages and from all social backgrounds, and are generally strong and independent. This aligns with the remarks from Toshio Suzuki, renowned producer of Studio Ghibli films, who describes Hayao Miyazaki as being quite simply a feminist.

Complex characters, sometimes anti-heroines

Hayao Miyazaki’s female characters are complex and ambivalent, like Princess Kushana in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke (1997), and the witches Yubaba and Zeniba in Spirited Away (2001). With regard to the heroines, San, better known as Princess Mononoke, sets herself apart due to her strength and her courage to save the forest from the cruelty of humans, of whom she is suspicious, having been raised by wolves. In Porco Rosso (1992), Fio, a 17-year-old female mechanic, fights to earn respect in a very masculine universe, and one which is even more so in Italy in the inter-war period. Her teenage determination allows her to win the respect of the men around her. In Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), the heroine is an 18-year-old girl, Sophie, who is turned into an old woman by a witch. Over the duration of the film, Sophie gradually accepts her new body, just as the viewer becomes accustomed to her new appearance, that of an old woman but one who is nevertheless courageous and determined.

However, the most striking example is that of Chihiro, one of Studio Ghibli’s most iconic characters. This fearful little girl finds herself alone in a fantasy world, far from her parents, who she still tries to save. Her ordinary nature is her strength, because she embodies a child like any other, and is therefore easily identifiable. In the film, she is described as ‘naughty’, ‘fragile’, and ‘tiny’, the complete opposite of what would usually be expected of a heroine, and Hayao Miyazaki’s remarkable feat lies in depicting femininity in a more realistic, real manner.

The image of the mother as a figure of authority

The filmmaker was heavily inspired by his own mother, a particularly strong woman who raised him and his brothers. ‘In my family, it was a very male universe. I only have brothers, the only woman was my mother’, Hayao Miyazaki declares. This is why numerous characters in his body of work represent her implicitly, like Satsuki and Mei’s mother in My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Nahoko Satomi (Jiro Horikoshi’s wife) in The Wind Rises (2013), and Dola, the air pirate in Castle in the Sky (1986).

Hayao Miyazaki’s heroines go against the stereotypes promoted by the animated film industry, or indeed the film industry in general. Their adventures are quests for emancipation, with the aim being self-fulfilment, helping each other, and humanity. However, while these female characters do not want to become men, they also display no contempt towards them. These women are fair, and possess strong values like compassion, love, tolerance, and respect. They are exemplary and benevolent and they are themselves, and this is what makes them universal.

More information about Hayao Miyazaki’s films can be found on the official Studio Ghibli website.

Mei and Satsuki in ‘My Neighbour Totoro’ © Studio Ghibli

Sen/Chihiro in ‘Spirited Away’ © Studio Ghibli

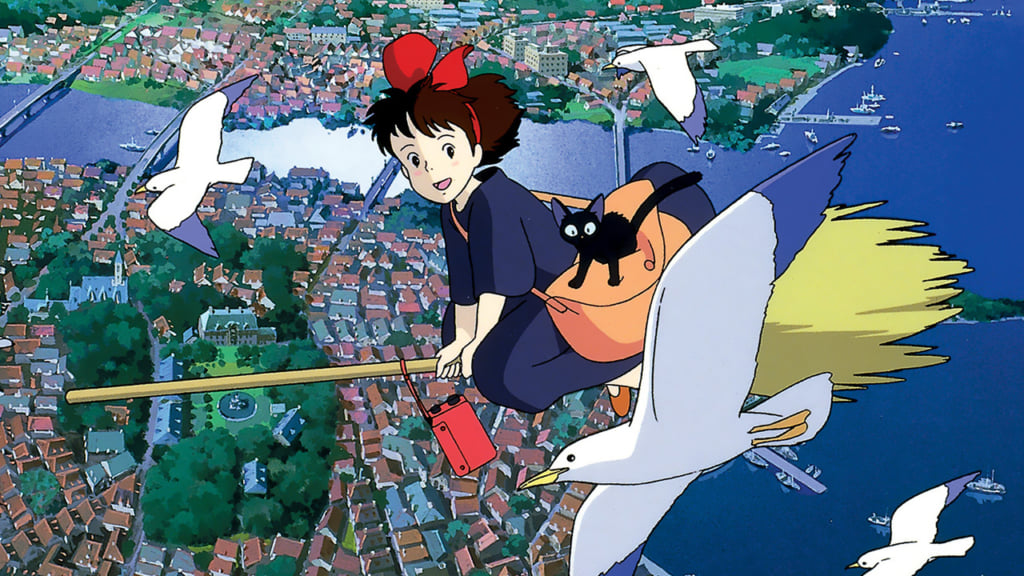

‘Kiki's Delivery Service’ © Studio Ghibli

Fio in ‘Porco Rosso’ © Studio Ghibli

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.