Rituals of Ancient Gay Shunga Erotica

Shunga was prolific in Japan during the Edo period, with ‘nanshoku’ referring to the depiction of homosexual erotica.

Nishikawa Sukenobu

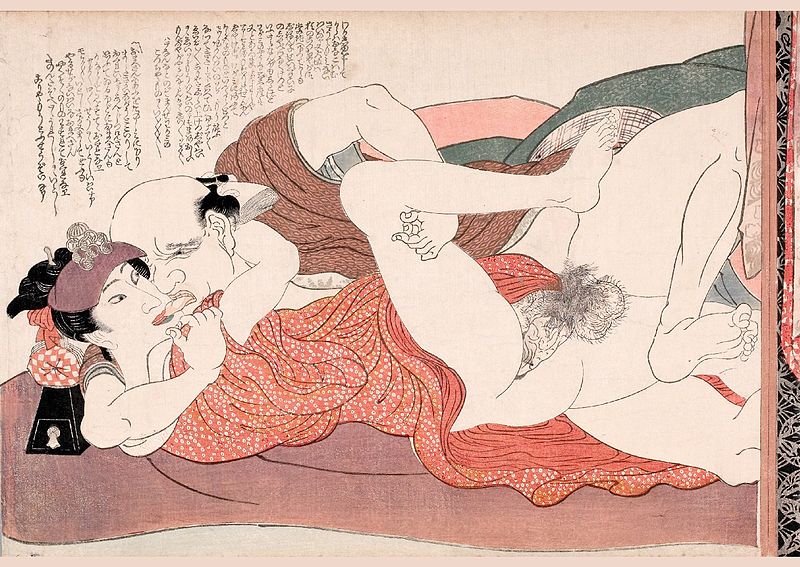

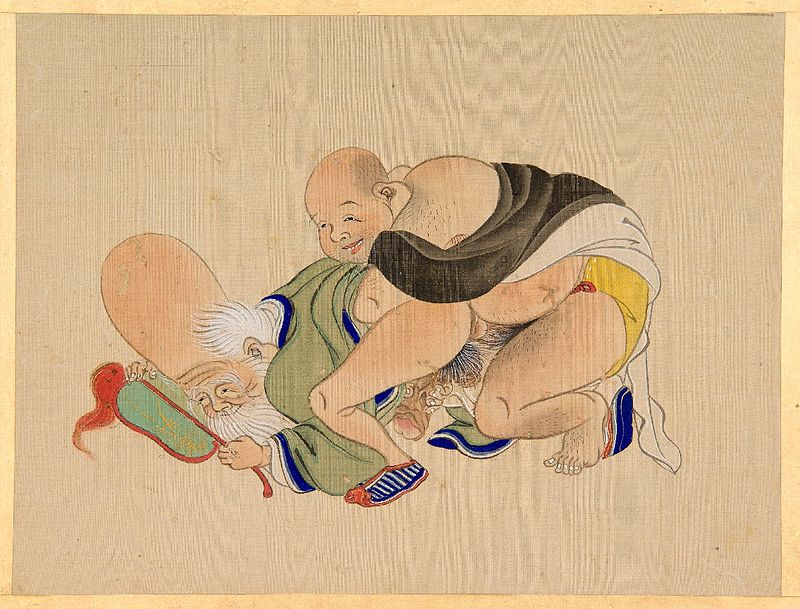

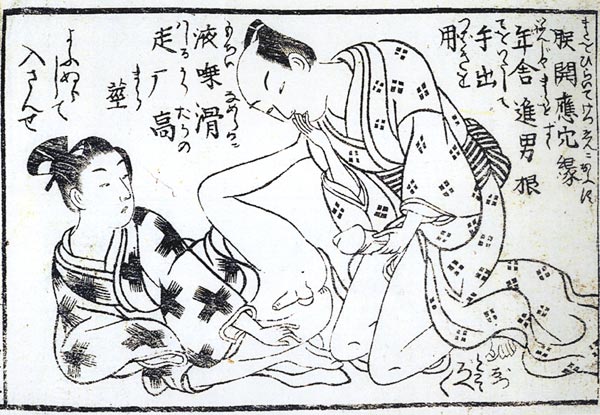

One notable vein of shunga is nanshoku, translating as ‘male colours’ and referring to gay erotic depictions. Images derived from ancient myth, the military, religion, theatre, class, and prostitution feature samurai or Buddhist monks engaging in gay sex with men often dressed as geisha.

Shunga, or Japanese erotic art, was prolific in Japan during the Edo period, from 1603 to 1868. Printed with woodblock and produced in a broad spectrum of colours and details, the scrolls were intimate, erotic, and sometimes humorous. The aesthetic is said to be influenced by the illustrations of Chinese medicine manuals as well as the work of Zhou Fang, a Chinese painter from the Tang dynasty era who painted oversized genitals, which later became characteristic of many shunga artists.

Roles and Rituals

The scenes contain a complex morality when considered by contemporary standards. The images often depict a sexuality derived from practices within monasteries when an older partner such as a priest or a monk would have sex with a younger, often pre-pubescent partner. These religious practices were replicated in samurai circles, and young samurai would be sent to Buddhist monasteries during training. Many would enter into same sex relationships with older monks.

This age-structured sexuality came to be known as shudo, meaning ‘way of the young’. The prevalence of male homosexuality has often been attributed to the gender imbalance of the population during the Edo period, which was about 70% male, and the scenes in which partners are dressed in women’s attire refers to onnagata from Kabuki theatre, where men would play women’s roles.

Shunga, which euphemistically translates as ‘pictures of spring,’ is an important aesthetic reference in Japanese culture, with even artists such as Hokusai producing work in this vein.

Yanagawa Shigenobu I Nanshoku

Unidentified Artist

Miyagawa Chosun Nanshoku 1

Suzuki Harunobi, F.M. Bertholet Collection

TRENDING

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

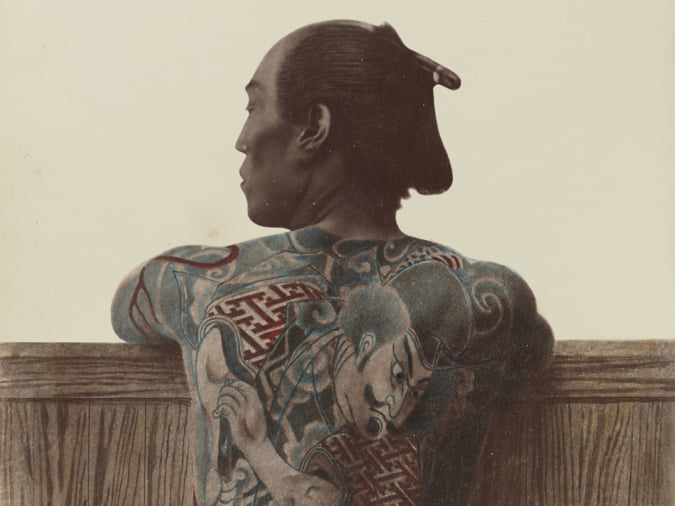

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

‘YUGEN’ at Art Fair Tokyo: Illumination through Obscurity

In this exhibition curated by Tara Londi, eight international artists gave their rendition of the fundamental Japanese aesthetic concept.