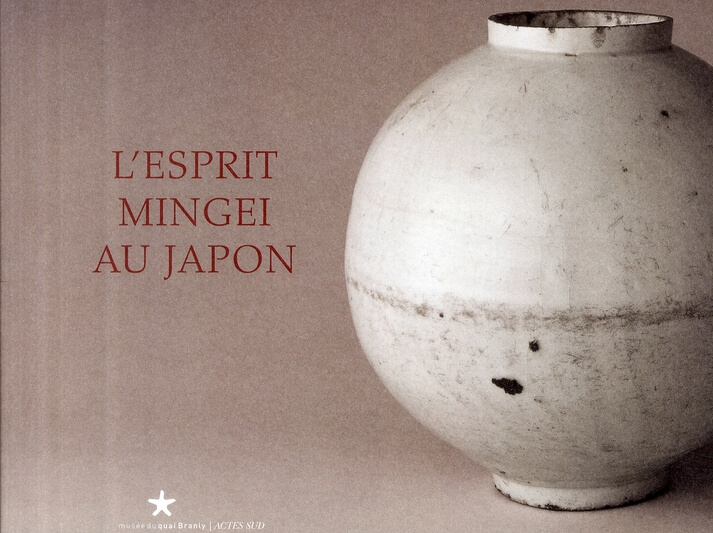

‘The Mingei Spirit in Japan’, the Revival of Traditional Folk Art

This artistic movement emerged in the 1920s with the objective of reiterating the value of Japanese craftsmanship.

© Musée du quai Branly / Actes Sud

In his book published in 2008, L’Esprit Mingei au Japon (‘The Mingei Spirit in Japan’), general curator of heritage Germain Viatte reveals the secrets of the success of this new artistic movement, between tradition and modernity.

Facing a country that only considered aristocratic art and the uniformity of globalisation, Japanese philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961) decided to reassert the beauty of everyday objects (getemono). Thus, a new generation of artists and artisans adopted the mingei movement, using natural and high-quality materials. While remaining contemporary, the pieces, mainly derived from pottery and ceramics, are adorned with simple colours and motifs. Authenticity, modernity and simplicity are the watchwords for this approach. ‘It needs to be modest but not shoddy, inexpensive but not fragile. Dishonesty, perversity, luxury: these are what mingei objects must absolutely avoid’, wrote the founder of the movement, Soetsu Yanagi, in The Meaning of Mingei (1933).

A spiritual dimension

In addition to the value of the fundamentals of Japanese craftsmanship, the spiritual dimension of everyday objects is revealed. According to the principle of the Path of Buddhism, tariki (‘other power’ in Japanese), truth transcends self-awareness. It therefore makes it possible to produce creations that are both proper and durable, beyond the notions of beautiful and ugly.

‘The extraordinary is far from the ideal. There is no ideal that surpasses the ordinary. The usual is the ultimate state of things’, Soetsu Yanagi explained in Craft Culture (1941). As a result, the founder of the mingei artistic movement selected products made by unknown artisans, lacking in technical virtuosity. Thus, he assesses their virtue (toku) through moral terms including certainty (kakujitsu), reliability (chusei) and sincerity (seijitsu).

A dialogue with the West

The objective of the spirit of mingei is not exclusively to showcase a popular Japanese traditional art; it needs to be given worldwide visibility. Consequently, the Japanese philosopher created a commercial network thanks to the press and department stores, as well as organising exhibitions, for example at the Mingei International Museum.

‘The artisan-artist needs to give guidelines for the future, improve the situation and ultimately enable craftsmanship to be transmitted to the working class. The objectives of all the efforts must not work towards personal expression, but rather towards the concrete appearance of beauty within folk art’, Soetsu Yanagi stated in The Way of Craft (1927-1928). An awareness set in as Japan progressively opened up thanks to three international experts. Urban planner Bruno Taut, architect Charlotte Perriand and sculptor Isamu Noguchi were involved in establishing a link between appreciation of craftsmanship and modernity. Subsequently, Sori Yanagi, the son of Soetsu Yanagi and collaborator of Charlotte Perriand, examined this further in pieces at the intersection between Japanese aesthetics and Western design.

L’Esprit Mingei au Japon (‘The Mingei Spirit in Japan’) (2008), a book by Germain Viatte published by Actes Sud (not currently available in English).

© Mingei International Museum. Purchase. Photograph by Lynton Gardiner.

© Mingei International Museum. Gift of Sueo and Marsha Serisawa. Photograph by Lynton Gardiner.

Mingei International Museum. Gift of Peter and Natalia OReilly. Photograph by Lynton Gardiner.

TRENDING

-

Ishiuchi Miyako, A Singular Perspective on Women

Recipient of the 2024 Women in Motion Award, the photographer creates intimate portraits of women through the objects they left behind.

-

Recipe for Ichiraku Ramen from ‘Naruto’ by Danielle Baghernejad

Taken from the popular manga with the character of the same name who loves ramen, this dish is named after the hero's favourite restaurant.

-

Namio Harukawa, Master of Japanese SM Art

'Garden of Domina' offers a dive into the world of an icon of ‘oshiri’, whose work has now reached a global audience.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Emperor of Japanese Porn is Now the Star of a Netflix Series

Deliciously funny, The Naked Director especially succeeds in reviving the atmosphere that was so characteristic of 1980s Japan.