Japan’s Female Ceramists Celebrated on the International Stage

After the Second World War, women enriched the production of ceramics, breathing new life into the discipline.

From left: Koike Shoko, 2002, On loan from a Private Collection, USA; Hoshino Kayoko, Cut Out 16 – 12, 2016, On loan from Joan B Mirviss LTD; Ogawa Machiko, Heki-yuu ban; Blue-green/clear glazed vessel, 2008, On loan from Joan B Mirviss LTD

For a long time, women in Japan were allowed little involvement in the production of ceramics. Not permitted to create pieces, they were restricted to finishing, painting, and decorating items. That was until World War II changed everything: from the 1950s, women began to enrol in apprenticeship programmes, opened their own studios, and, collectively, breathed new life into ceramics.

From September 2018 until January 2019, the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, the only museum in Canada to be dedicated to ceramics, celebrated the ‘independence, creativity, and technical genius’ of these female artists in an exhibition entitled Japan Now: Female Masters. The pieces displayed, selected by New York-based collector Joan B. Mirviss, exemplify this new style of Japanese ceramics, liberated from codes and rules.

The work of female pioneers

Toshiko Takaezu, who passed away in 2011, is often cited as the pioneer of this movement. Throughout her career, she played a significant role in elevating ceramics from a craft to an art by forcing functionality to take a back seat: her works, in the shape of pebbles or cylinders, are sometimes minuscule and often oversized, and virtually always impossible to use in everyday life.

Many other female artists have followed in her footsteps over the decades. Their pieces, as creative as they are impractical, keep Toshiko Takaezu’s spirit alive. This is especially true of Sakurai Yasuko’s Flower vases (pierced with apertures, meaning they could never be filled with water) or those by Kishi Eiko, which can only hold one or two flowers at a time.

Among Toshiko Takaezu’s successors, Fujikasa Satoko, born in 1980, particularly stands out. Her fascinating body of work, in neutral tones, celebrates the fluidity of ceramics. The shapes and colours she uses recall the fabric Jeanne Lanvin would drape over mannequins in the early days of the eponymous fashion house.

These masterful pieces, which seem to be constantly in movement, pay homage to the words spoken by Toshiko Takaezu in 1975: ‘You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt pots that cannot be used’, she stated. ‘An artist is a poet in their own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive.’

Japan Now: Female Masters, an exhibition that took place from 7 September 2018 to 13 January 2019 at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto.

Fujikasa Satoko, Hiten; Seraphim, 2016, On loan from the Diana Reitberger Collection

Futamura Yoshimi, 2016, On loan from Joan B Mirviss LTD

Koike Shoko, 2002, Stoneware with creamy white, brown, and silver glazes, On loan from a Private Collection, USA

Hattori Makiko, Ryū: Flow, 2017, On loan from the Diana Reitberger Collection

Left: Ogawa Machiko, Heki-yuu ban; Blue-green/clear glazed vessel, 2008; Right: Katsumata Chieko, Akoda: Pumpkin, 2016, Both on loan from the Diana Reitberger Collection

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

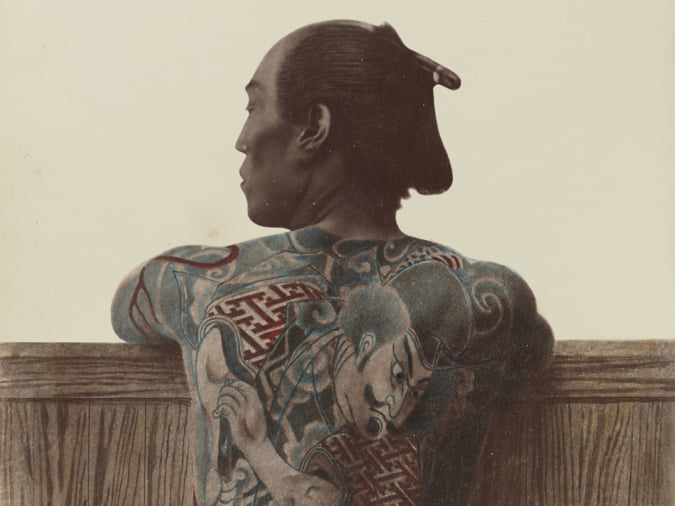

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

The Trendiest ‘Sento’ and Saunas in Tokyo

The bath culture remains vibrant in the capital city, where public baths and saunas designed by renowned architects are continuously opening.

-

Rituals of Ancient Gay Shunga Erotica

Shunga was prolific in Japan during the Edo period, with ‘nanshoku’ referring to the depiction of homosexual erotica.

-

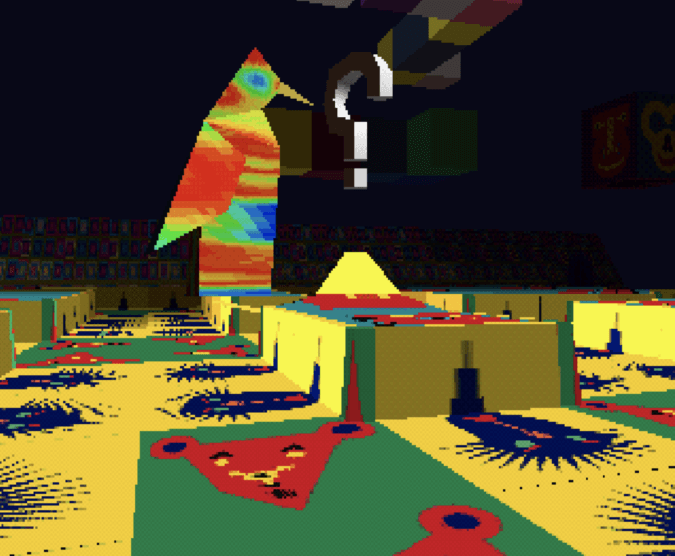

‘LSD: Dream Emulator’, an Avant-Garde Game Released on PlayStation

In this video game created by Osamu Sato and released in 1998, the player explores the surrealist, psychedelic environment of a dream.