How Japan’s Cherry Blossoms were Saved

Taihaku at The Grange, 2015 (Courtesy of the author)

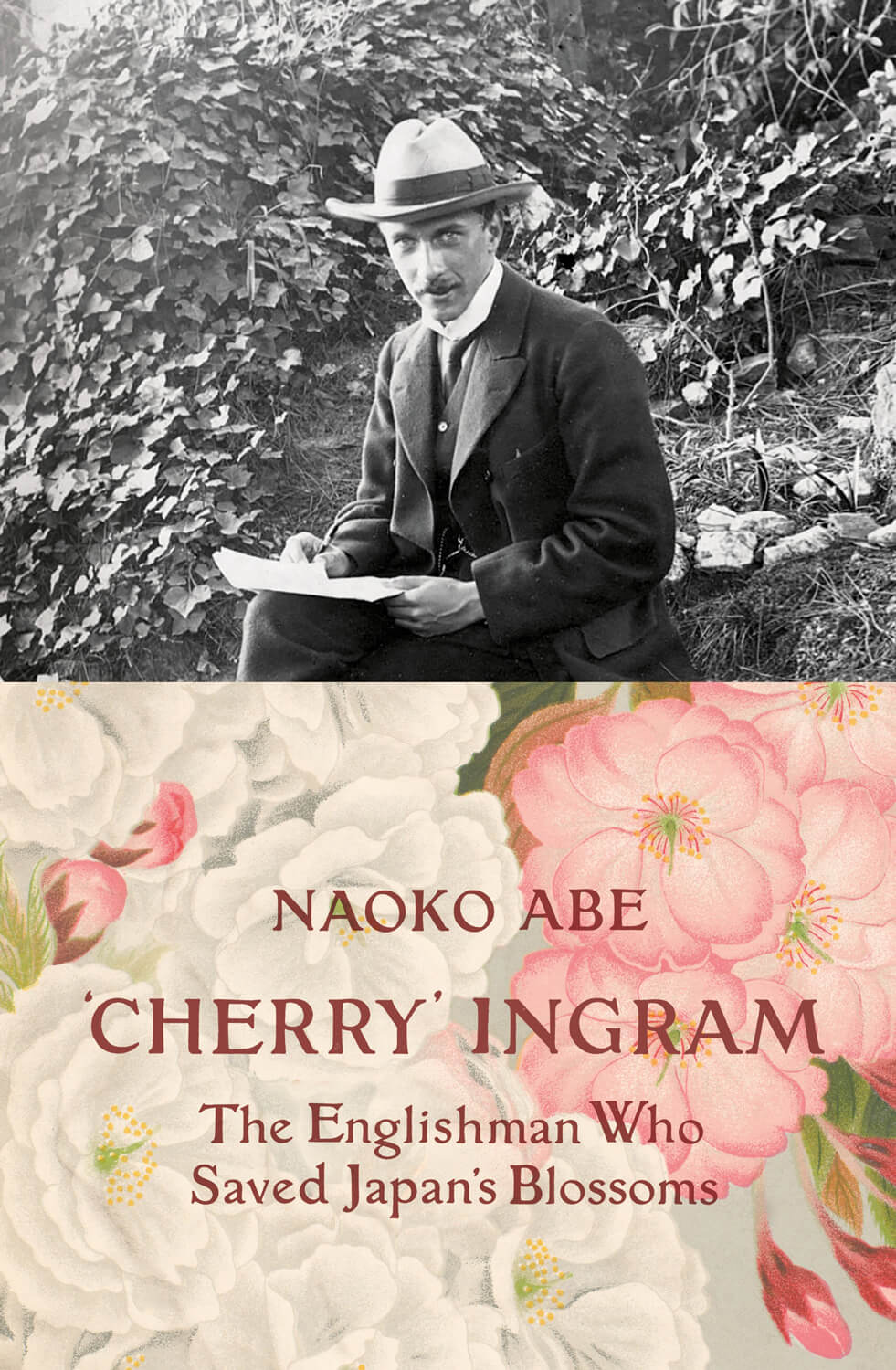

Each spring, cherry blossoms burst forth and the Japanese celebrate their splendour with great pageantry. However, Japanese spring once risked being much more gloomy without the intervention of Collingwood Ingram, an Englishman who stepped in to save the iconic flower. It is this surprising, yet very real story, that inspired the writer Naoko Abe who, after four years of research, to publish the book ‘Cherry’ Ingram: The Englishman Who Saved Japan’s Blossoms.

“I have lived in London since 2001 and have marvelled at the cherry blossoms in the UK and I love them because they signify life, hope and vigour”, says Naoko Abe. “Cherry trees blossom in the UK are very diverse, many different varieties are planted which are different colours and shapes. They blossom at different times over about two months. In Japan, there are thousands of cherry trees, but at least in urban areas, one variety dominates, the Somei-yoshino. These blossom all together and create a spectacular sight as they are all clones. But it lacks diversity. I wondered why the two countries’ cherry scenery was so different, and in 2014, I started digging into the question. I researched and talked to horticulturalists in the UK and found out that there was an Englishman who fell in love with the Japanese cherry trees at the beginning of the 20th century, and that he valued the diversity of the blossoms.” Following numerous interviews with Collingwood Ingram’s descendants and mining his personal archives, Naoko Abe now recounts the romantic story of Ingram, a renowned ornithologist who turned to botany to study cherry tree culture in Japan.

In the race to modernise, Japan began constructing huge concrete towers on green spaces, and the cherry trees that came in their path were not spared. Scouring the land on horseback, boat, car and by foot, Ingram went in search of different varieties of cherry trees in the hope of saving them, aware that these trees were withering quickly. “When Ingram went to Japan in 1902, 1907 and 1926, he discovered that Japanese were no longer interested in cherry varieties and many of them were disappearing. The country was focused on modernisation and industrialisation to catch up with the West, and the trees were not a priority. So Ingram decided to save and preserve the disappearing varieties himself in his Kent garden.” explains Naoko Abe.

Over the course of his travels, he documented no less than 120 varieties of cherry trees that populated his garden, including new varieties obtained by hybridization such as the Kursar tree, the fusion of a variety from the north with a variety from the south of Japan. Anxious to restore Japan’s rosy splendour each spring, Ingram busied himself with repeatedly sending cuttings to the archipelago. After several unsuccessful attempts, a transplant tucked into a potato made its way to Japan.

Collingwood Ingram who died in 1981 at the age of 100 remains nicknamed Cherry. Thanks to his determination, Japan and visitors from across the globe can still enjoy the country’s cherry blossoms with the arrival of each spring.

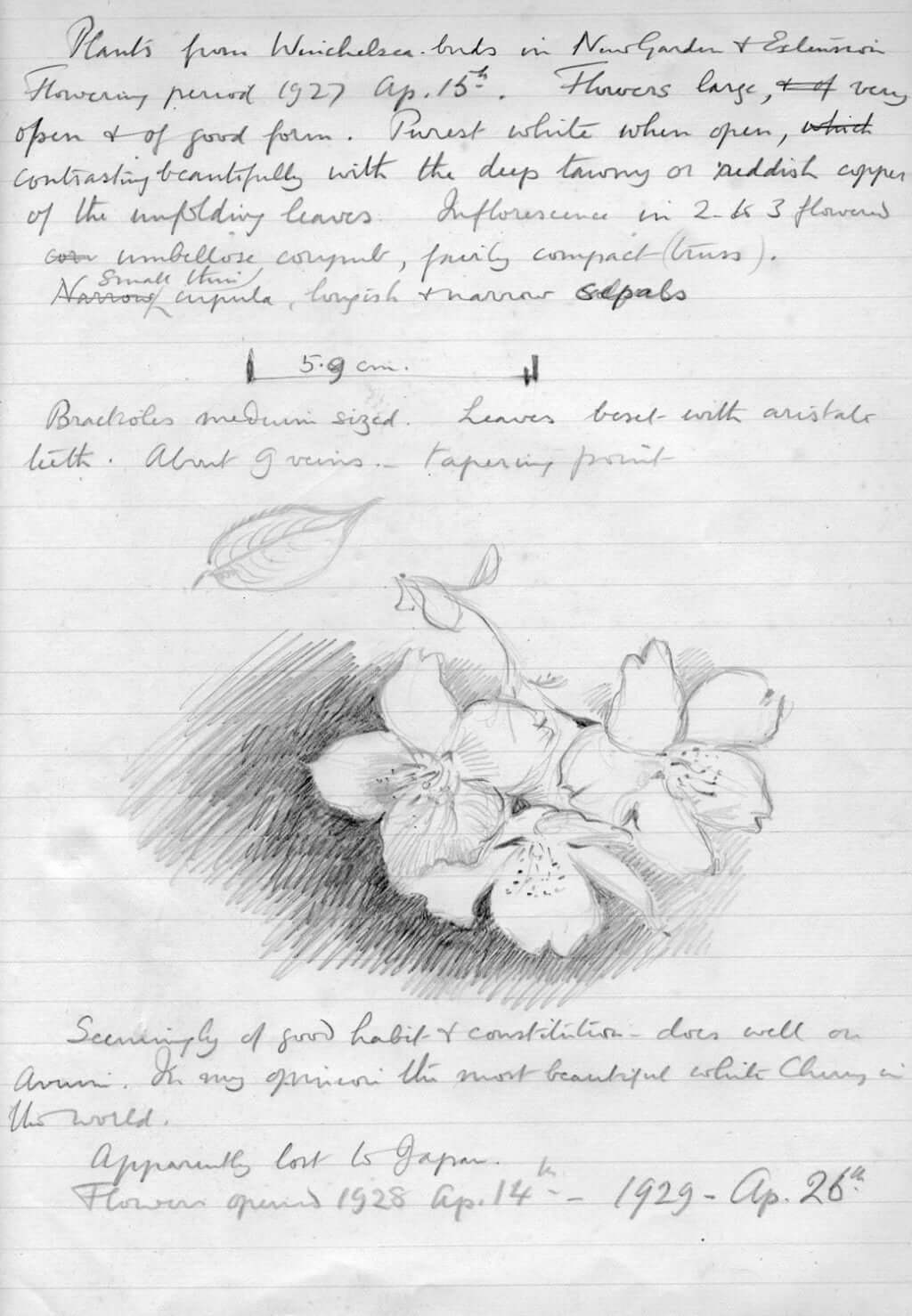

Kanhi-zakura, described as Prunus campanulata, 1941, and a Sargent cherry leaf, 1939, from Ingram's notebooks

Illustration from Ingram's notebooks, described as Prunus prostrata, 1944

Taihaku : a page from Ingram's notebooks, c. 1927

TRENDING

-

Gashadokuro, the Legend of the Starving Skeleton

This mythical creature, with a thirst for blood and revenge, has been a fearsome presence in Japanese popular culture for centuries.

-

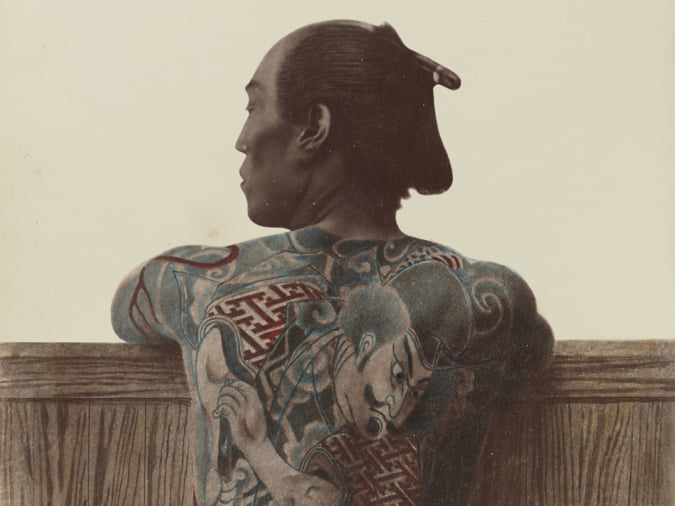

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.

-

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

‘YUGEN’ at Art Fair Tokyo: Illumination through Obscurity

In this exhibition curated by Tara Londi, eight international artists gave their rendition of the fundamental Japanese aesthetic concept.