The Virtues of the Tea Ceremony in the Digital Age

In a world where everyone has a smartphone and internet access which enable them to be permanently connected, but which make it difficult to get away from distractions, the ancient art of the Japanese tea ceremony appears in a new light.

Long considered as rigid and elitist due to its many rules which represent everything that young Japanese people find stifling in society, it has recently come back into fashion, including among the younger generation.

From the religious to the informal

This is illustrated in the film Every Day a Good Day by director Tatsushi Omori, adapted from the autobiography of Noriko Morishita. In it, Noriko, then a student, seeks to fill her free time and turns her attention to the tea ceremony in response to her mother’s suggestion. She then takes lessons with Madame Takeda (played by popular actress Kirin Kiki in her last appearance on screen before her death in September 2018) and forgets her initial reluctance, letting herself get caught up in the temporality of the tea ceremony.

Cha-no-yu, its alternative name which literally translates as ‘hot tea water’, has been anchored in Japanese culture since its emergence with the spread of zen Buddhism in the 9th century. Originating from religion, this ceremony centred on matcha tea has not always been synonymous with ritual or had sacred status. On the contrary, in the 13th century, when cha-no-yu was adopted by the warrior caste, it was primarily about sharing a moment with friends. A lord would even organise a tea ceremony lasting almost ten days, like a grand festival.

Such excesses led certain lords to set guidelines for the practice of cha-no-yu and give it the form we know today, which was codified by Sen-no-Rikyu (1520-1591), Japan’s most famous tea master, and his descendants then created the three currents of cha-no-yu practice which persist today: the Omotesenke, Urasenke and Mushanokoji-senke families. For those wishing to learn more about the codes of the tea ceremony and the various instruments required, Kakuzo Okakura has compiled all the necessary information in The Book of Tea, published in English in 1906 and which has acted as the authority on the subject ever since.

A primarily aesthetic approach

The true essence of the tea ceremony, however, lies beyond the rules. In their book Japanese Civilisation, historians Danielle and Vadim Elisseeff write: ‘Cha-no-yu involves savouring together the joys of calm contemplation and appreciating the products of a refined art. The setting, the everyday objects, the gestures of the person who prepares the tea, everything must serve to transport the participants far from the difficulties of this world and elevate them to the pure joy of aesthetic contemplation’.

This joy is found in the film Every Day a Good Day, where the sounds of nature, whether water running or the rustling of leaves, predominate, with no soundtrack to distract the viewer. Its sobriety and restraint enable the viewer to contemplate the narrative which is marked by no spectacular action but where the precise, many times repeated gestures of the tea ceremony encourage us to slow down, disconnect and put things in perspective.

By naturalogy from Pixabay

TRENDING

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

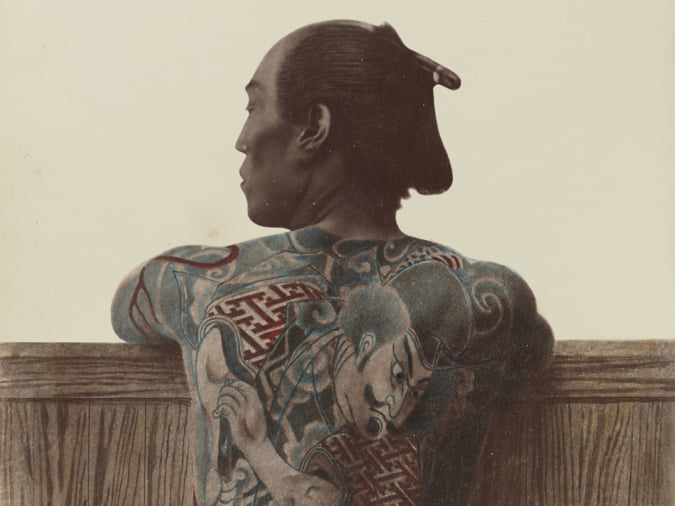

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

The Trendiest ‘Sento’ and Saunas in Tokyo

The bath culture remains vibrant in the capital city, where public baths and saunas designed by renowned architects are continuously opening.

-

Rituals of Ancient Gay Shunga Erotica

Shunga was prolific in Japan during the Edo period, with ‘nanshoku’ referring to the depiction of homosexual erotica.

-

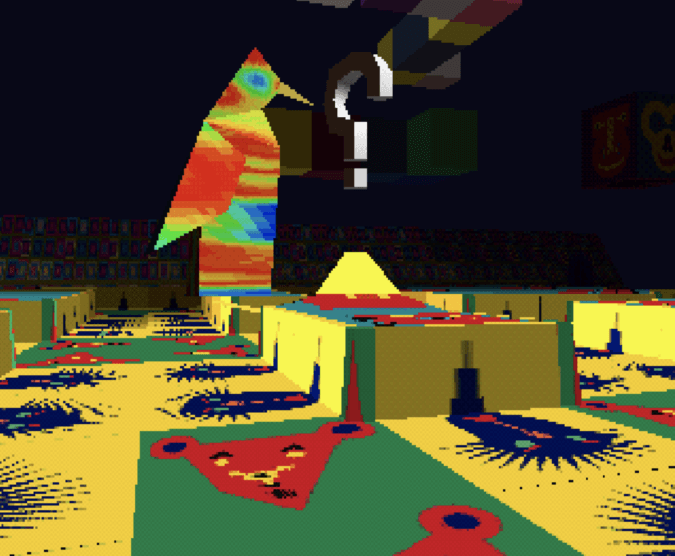

‘LSD: Dream Emulator’, an Avant-Garde Game Released on PlayStation

In this video game created by Osamu Sato and released in 1998, the player explores the surrealist, psychedelic environment of a dream.