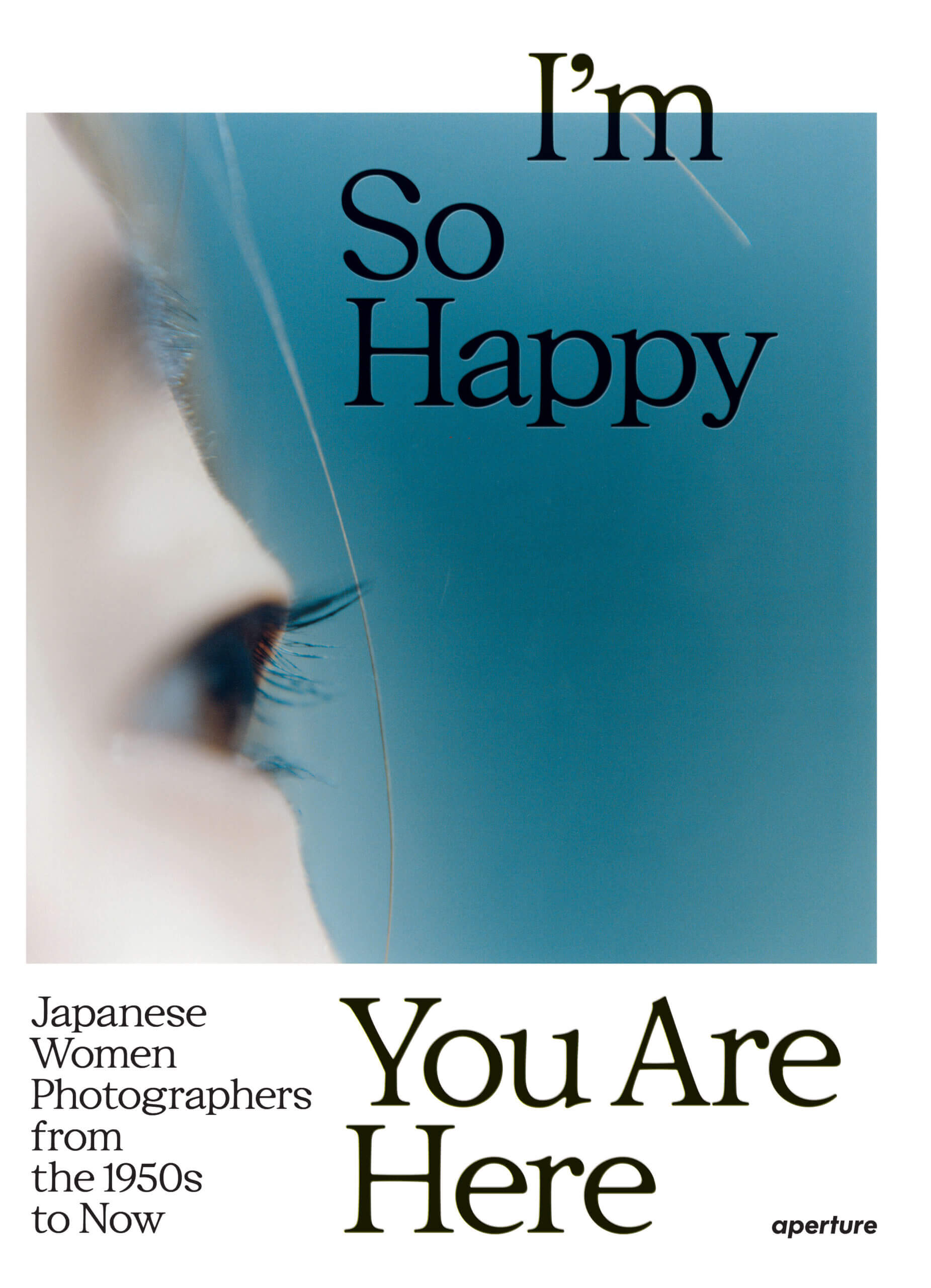

‘I’m So Happy You Are Here’, A History of Japanese Women in Photography

Long overlooked, the works of Japanese female photographers are finally being celebrated through a new book and exhibition.

Okabe Momo, ‘Untitled’, 2020, from the ‘Ilmatar’ series © Okabe Momo, courtesy of Aperture.

Japan, a major player in photography since the arrival of the technology in the 19th century, is home to numerous photographers, studios, and leading industry companies. However, in the ranks of renowned Japanese photographers both domestically and internationally, women have long been underrepresented despite being just as talented as their male counterparts. A new exhibition and a major book aim to address this imbalance.

I’m So Happy You Are Here — Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now, which debuted at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival (on view until September 29, 2024, at the Palais de l’Archevêché), is the result of extensive work coordinated by three curators: Lesley A. Martin, Takeuchi Mariko, and Pauline Vermare. Through the works of around twenty artists, they seek to construct a parallel history of Japanese photography, showcasing the creativity of women from various generations who have continuously experimented with and explored their medium, contributing to its development and renewal.

A Long-Awaited Recognition

The official history of Japanese photography has often been written without women. Seminal exhibitions of Japanese photographers, including those abroad like the one organized by MoMA in 1974, rarely included them. While some pioneers like Ishiuchi Miyako or Ishikawa Mao have received recognition, it remained insufficient. Between 1997 and 1999, publisher Iwanami Shoten released a forty-volume series on Japanese photographers, Nihon no Shashinka. Not a single woman was featured. For its first 25 years, the illustrious Kimura-Ihei Prize, which honors young photographers, was never awarded to a woman. It wasn’t until 2000 that it was given to three women simultaneously: Nagashima Yurie, Ninagawa Mika, and Hiromix.

These photographers are part of a generation that emerged in the 1990s, placing the experiences of young women at the center of their work. Hiromix became known for her series Seventeen Girl Days, which documents her daily life as a high school student, utilizing self-portraiture. Ninagawa Mika’s work, which also involves self-portraits, is distinguished by her bold use of color. Their approach could even be seen as a precursor to the Instagram era. Nagashima Yurie stages herself in a more provocative manner, posing nude with other family members in a black-and-white series. By representing her own body, she challenges the stereotypes that often confine women to the role of erotic subjects in front of the camera, asserting her place behind the lens. Her work openly aligns with a feminist perspective, opposing the term ‘Girly Photo’ used by Japanese critics to describe the work of female artists of her generation, implying inferiority.

An Approach Not Limited to Gender

The work of Japanese female photographers cannot be reduced to a single category. Within the exhibition I’m So Happy You Are Here, Nagashima Yurie, Hiromix, and Ninagawa Mika are all highlighted, but in separate spaces. The perspectives and creative processes of Japanese female photographers are diverse, and they have rarely formed collectives. However, the subjects they choose to explore sometimes converge.

Their experience as women, an experience inaccessible to men, has naturally influenced their work. But Lesley A. Martin notes that ‘the diversity of their styles and approaches proves that these women’s works are not limited to gender. They may have been more focused on elevating the everyday, paying attention to household details, while men were more interested in the medium and materiality (a passion shared by some artists presented here). To embrace their own style, these women took from the vernacular, drew on elements ignored by the mainstream patriarchal society, and found creativity and expression in them.’ This is exemplified by the powerful series by Ushioda Tokiko, My Husband, created in the 1970s and 1980s, in which the artist captures snapshots of her daily life and family. The work was only published in 2022, after she found the photographs in her storage unit.

Experimental Photographs Relegated to the Margins

As Takeuchi Mariko writes in her essay in I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now (Aperture, 2024), ‘many female photographers… are distinguished by how they have overcome, circumvented, or challenged the values and norms of the photographic institutions that governed the field in their time.’ Japanese female photographers have often taken an experimental approach, which has naturally placed them on the margins. They have, among other things, distinguished themselves by their use of color at a time when male photographers from the Provoke movement were celebrated for their high-contrast black-and-white images. ‘Color was considered more mundane,’ explains Lesley A. Martin. ‘It wasn’t really used in an artistic context. Women used it to experiment and develop a unique sense of color that has marked the history of the medium, from the electric palette of Okabe Momo to the watercolor-like tones of Kawauchi Rinko.’

Today, women continue to innovate in their approach to photography, burning or transforming images into other objects like Tawada Yuki, or using immersive and performative techniques like Komatsu Hiroko, who took over a room in the Palais de l’Archevêché by covering the walls and floor with her photographs and videos.

Creating in Response to Sexist Systems

In an essay within the book accompanying the exhibition, Carrie Cushman and Kelly Midori McCormick, the founders of the site Behind the Camera: Gender, Power, and Politics in the History of Japanese Photography, conclude: ‘For the artists we highlight […] being women is fundamental: their work, their careers, and their impact are shaped in response to (and despite) the sexist systems that govern women’s personal, social, economic, and political lives. This essay is less about rehabilitation and more about shedding light on artists who are creating new audiences and communities through their photographs, revealing much about the worlds against which they struggle.’

This intention is particularly well illustrated by a verse from a poem by photographer Kawauchi Rinko, chosen by the curators as the exhibition’s title.

once in a while,

we should look into each others eyes.

otherwise we might feel lost.

I’m so glad

that you are here.

—Kawauchi Rinko, the eyes, the ears.

I’m So Happy You Are Here — Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now (2024), an exhibition organized by Lesley A. Martin, Takeuchi Mariko, and Pauline Vermare at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, at the Palais de l’Archevêché until September 29, 2024.

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now (2024), a photography book coordinated by Lesley A. Martin, Pauline Vermare and Takeuchi Mariko, with contributions from Carrie Cushman, Kelly Midori McCormick, Marc Feustel, and Russet Lederman, published by Aperture.

Kawauchi Rinko, ‘Untitled’, ‘the eyes, the ears’ series, 2002-2004. Courtesy of the artist / Aperture.

Ushioda Tokuko, ‘Untitled’, 1983, from the series ‘My Husband’ © Ushioda Tokuko, courtesy of PGI and Aperture.

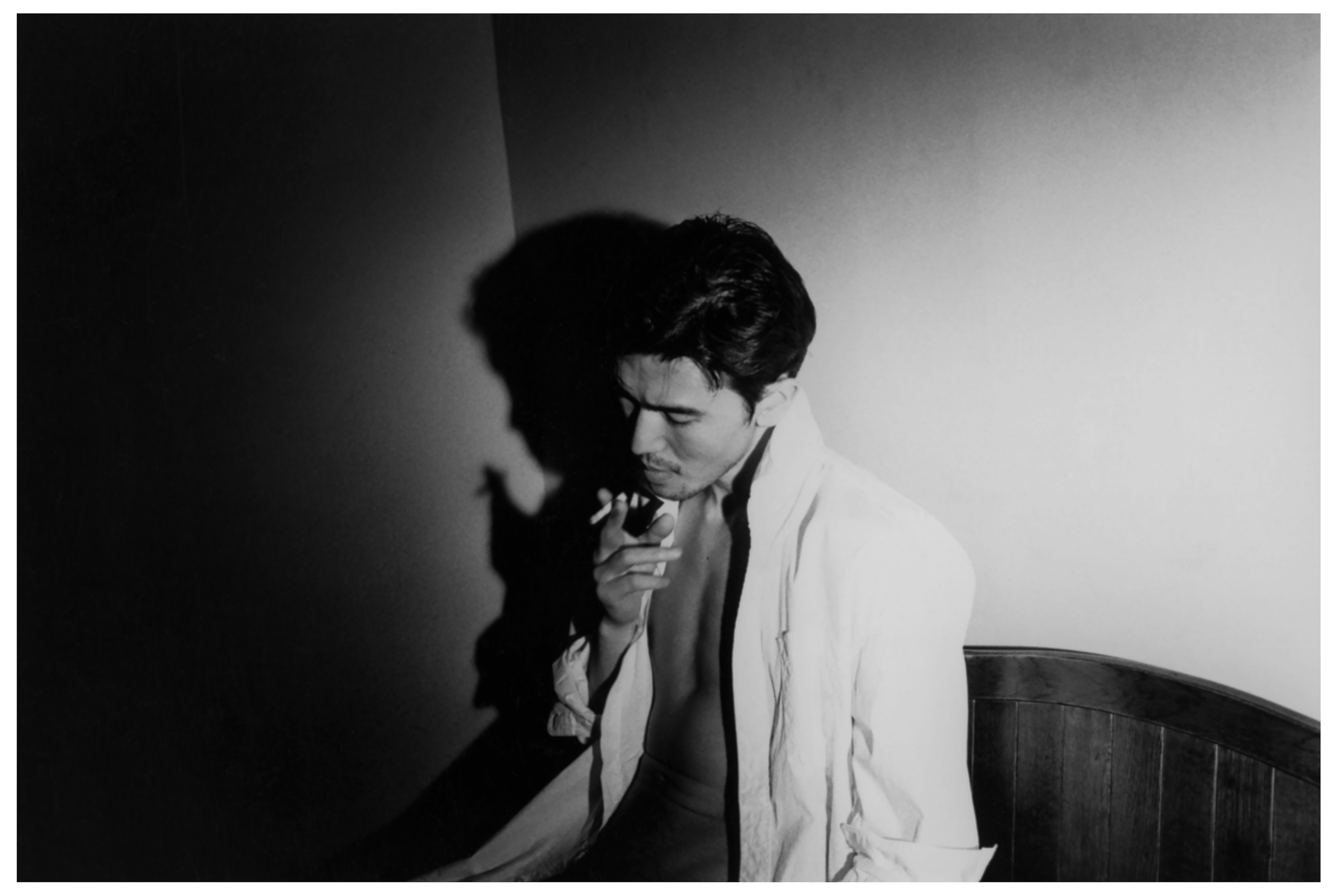

Nomura Sakiko, ‘Untitled’, 1997, from the series ‘Hiroki’. Courtesy of the artist / Aperture.

Narahashi Asako, ‘Kawaguchiko’, 2003, from the series ‘half awake and half asleep in the water’. Courtesy of the artist / PGI / Aperture.

‘I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now’ (Aperture, 2024)

TRENDING

-

Hiroshi Nagai's Sun-Drenched Pop Paintings, an Ode to California

Through his colourful pieces, the painter transports viewers to the west coast of America as it was in the 1950s.

-

A Craft Practice Rooted in Okinawa’s Nature and Everyday Landscapes

Ai and Hiroyuki Tokeshi work with Okinawan wood, an exacting material, drawing on a local tradition of woodworking and lacquerware.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

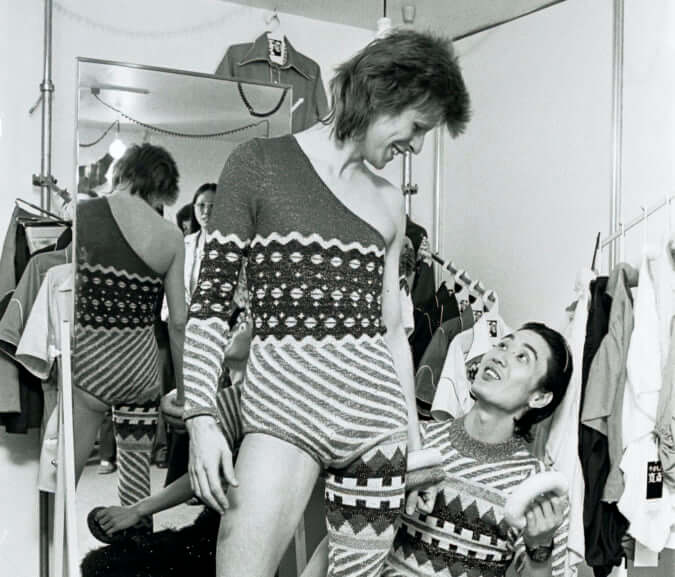

David Bowie Dressed by Kansai Yamamoto

The English singer was strongly influenced by 'kabuki' theatre and charged the Japanese designer with creating his costumes in the 1970s.

-

‘Seeing People My Age or Younger Succeed Makes Me Uneasy’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.