‘Drive My Car’, Relationships and Grief

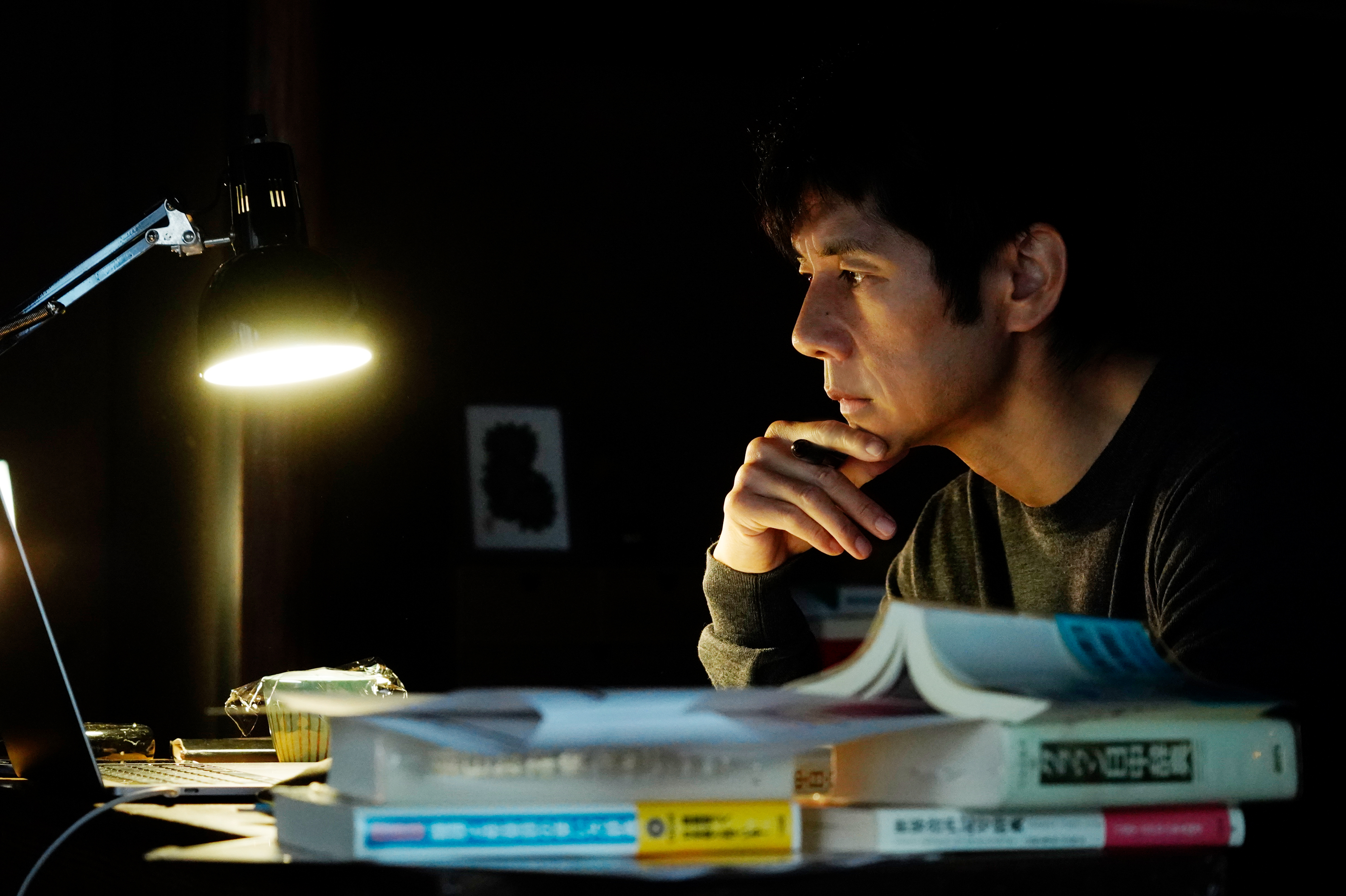

Director Ryusuke Hamaguchi adapts the work of author Haruki Murakami in a film that addresses creativity and repentance.

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

Adapted from three short stories by Haruki Murakami, one of which lends its name to the film (and all of which are from the collection entitled Men Without Women), Drive My Car won the award for Best Screenplay at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a BAFTA, Golden Globe and the Oscar for Best International Film in 2022, confirming Japanese director Ryusuke Hamaguchi‘s critical and public success.

Born in 1978 in Kanagawa prefecture in Japan, Ryusuke Hamaguchi is a director and screenwriter. After graduating with a degree in art from the University of Tokyo in 2003, he worked as an assistant director for film and television for three years. He then studied at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, where he directed Passion in 2008, his graduate film that was extremely well received by his professors, including director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. The film was lauded at the San Sebastian International Film Festival and Tokyo Filmex. He continues with a string of projects, including a trilogy of documentaries co-directed with Ko Sakai, in which they gave a voice to the victims of the earthquake that struck the Pacific coast of Japan in 2011 and led to the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Considered as one of the most promising talents in the new generation of Japanese directors, Ryusuke Hamaguchi has received great praise at various international festivals. In 2015, his film Senses (a choral fresco that is over five hours long) received the award for Best Collective Female Performance at the Locarno Film Festival. In 2018, Asako I & II was part of the official selection at Cannes Film Festival. In 2021, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was presented at the Berlinale, where the director received the Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize. That same year, the filmmaker adapted the work of Haruki Murakami for the film Drive My Car, which achieved critical and public success worldwide.

Repentance of two individuals who are total opposites

While struggling to recover from a personal tragedy, Yusuke Kafuku, an actor and theatre director, agrees to direct an adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s Oncle Vania for a festival in Hiroshima. There, he meets Misaki, a young, reserved woman in her twenties who is assigned to him as his chauffeur. Yusuke is initially reluctant at the prospect of handing her the keys to his car, a red Saab 900 that is in perfect condition and easy to spot. However, Misaki turns out to be an excellent driver. She maintains a respectful silence while driving as Yusuke goes over the dialogues for his play while listening to cassettes belonging to Oto, his wife who passed away two years earlier. Over the course of their journeys, the increasing sincerity of the conversations between Yusuke and Misaki forces them both to face up to their past.

Drive My Car mainly depicts two characters, Yusuke and Misaki, confronting their pain in a closed, moving space: Yusuke’s car. The artist’s vehicle is a symbol of comfort, a bubble in which both protagonists become more vulnerable, more open. In this space characterised by freedom and solitude, two individuals who were initially opposed grow closer, learning to listen, understand and respect each other. The car represents the movement and escape made by the two characters; an escape linked to tragic events they have experienced, like Misaki, who flees from her own guilt that lies buried in the ruins of a former life.

Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s film is sincere and touching, and addresses the key issues in the lives of every individual in many ways. Drive My Car deals with pain and secrets, bonds between individuals, things left unsaid and social appearance, sexuality and creativity, repentance and grief, love and death.

Drive My Car (2021), a film directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi and distributed by The Criterion Collection.

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

© 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, Bungeishunju, L’espace Vision, The Asahi Shimbun Company, C&I

TRENDING

-

Hiroshi Nagai's Sun-Drenched Pop Paintings, an Ode to California

Through his colourful pieces, the painter transports viewers to the west coast of America as it was in the 1950s.

-

A Craft Practice Rooted in Okinawa’s Nature and Everyday Landscapes

Ai and Hiroyuki Tokeshi work with Okinawan wood, an exacting material, drawing on a local tradition of woodworking and lacquerware.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

‘Seeing People My Age or Younger Succeed Makes Me Uneasy’

In ‘A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Surviving Society’, author Satoshi Ogawa shares his strategies for navigating everyday life.

-

‘Shojo Tsubaki’, A Freakshow

Underground manga artist Suehiro Maruo’s infamous masterpiece canonised a historical fascination towards the erotic-grotesque genre.